Interview: Cameroonian Artist Ethel Tawe On Haptic Images And The Black Interior

By Something CuratedEthel Tawe, born in Yaoundé, Cameroon, is a multidisciplinary artist and curator exploring visual and sonic archives, memory, and identity in Africa and its diaspora. Using collage, pigments, words, installation, still and moving images, Tawe examines space and time-based technologies often from a magical realist lens. Her burgeoning curatorial practice took form in an inaugural exhibition titled ‘African Ancient Futures’, and continues to expand in a myriad of audiovisual experiments. Whilst studying International Human Rights and Development Studies, Tawe’s academic research examined the safeguarding of tangible and intangible cultural heritage in Africa, informing her work experience with the African Union and organisations in The Hague. Tawe is presently in artist-in-residence at Grand Cayman estate, Palm Heights, where she is working closely with the property’s in-house library and bookshop, Library Fetish, to develop her ongoing work, Image Frequency Modulation. Over the course of Tawe’s residency and beyond, Something Curated will be hosting an editorial series extending and unpacking the project. Launching the four-part series, SC sat down with the artist to learn more about her practice and what she has planned during her time on the island.

Something Curated: Can you give us some insight into your background and journey to art-making?

Ethel Tawe: I declared myself an artist a few years ago after sitting with the awareness most of my life. I’ve always made art and my work is quite multidisciplinary. I started painting before working with photographs mostly through collage-making. My work stems from cultural research and writing which I continue to explore in my practice. I began exploring moving-image and montage more recently, through the lens of (re)understanding technologies and ‘the digital’. In his essay, Achille Mbembe states: “today, it is possible to move almost without transition from the Stone Age to the Digital Age, from magical reason to electronic reason. Time now unfolds in multiple versions while life and the world are increasingly experienced as cinema.” I think this illustrates how images can act as interfaces to time travel and access new horizons as African artifacts have long done; what Mbembe calls the ‘digital before the digital’. My first curatorial project was an exhibition ‘African Ancient Futures’ in Lagos Nigeria, examining the ways in which African artists bend time and carry histories forward. I continue to assemble and gather material in a time-based experiment called @listening2images, informing a hybrid/collective approach to my art practice.

SC: Introduce us toImage Frequency Modulation — how was the project born?

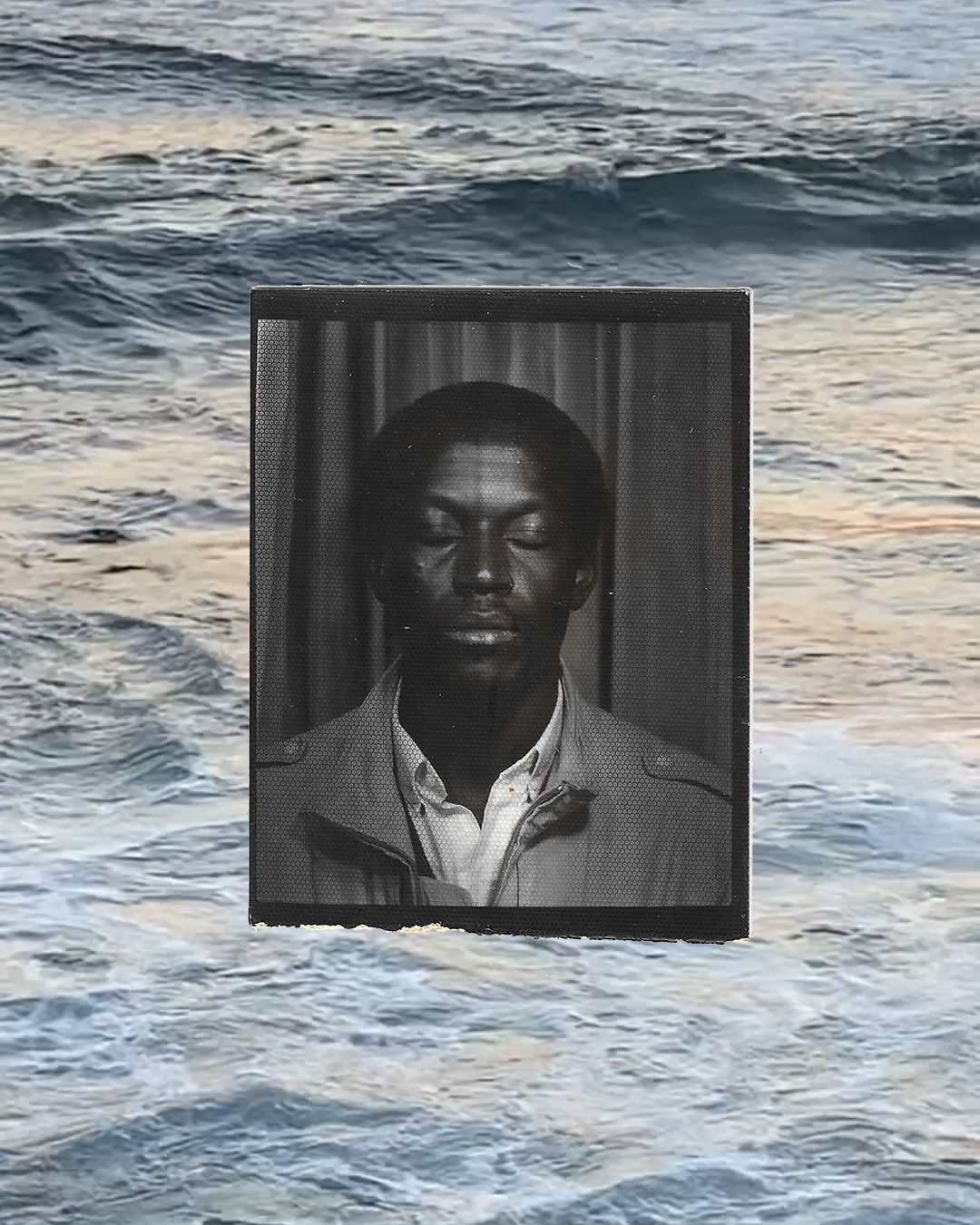

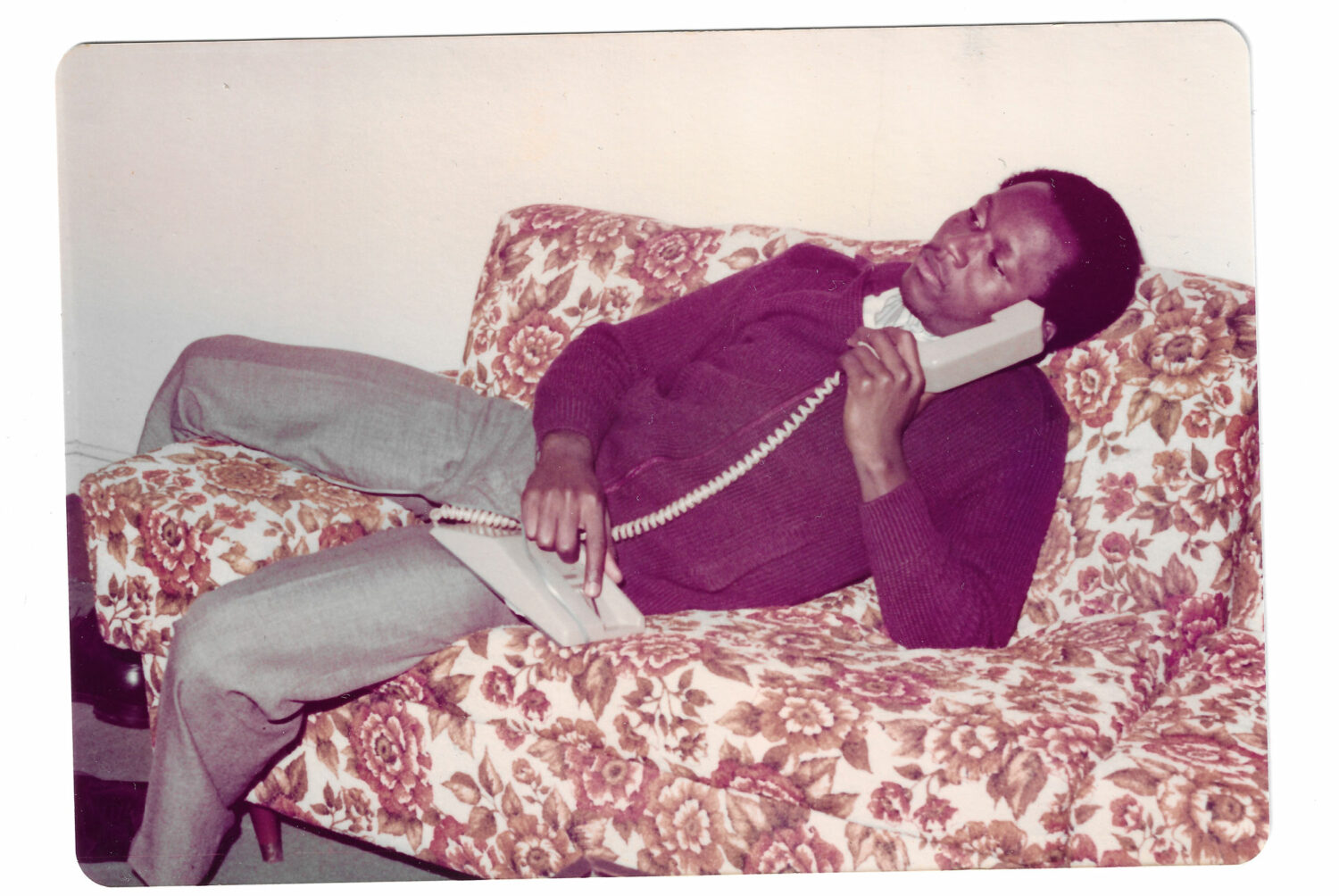

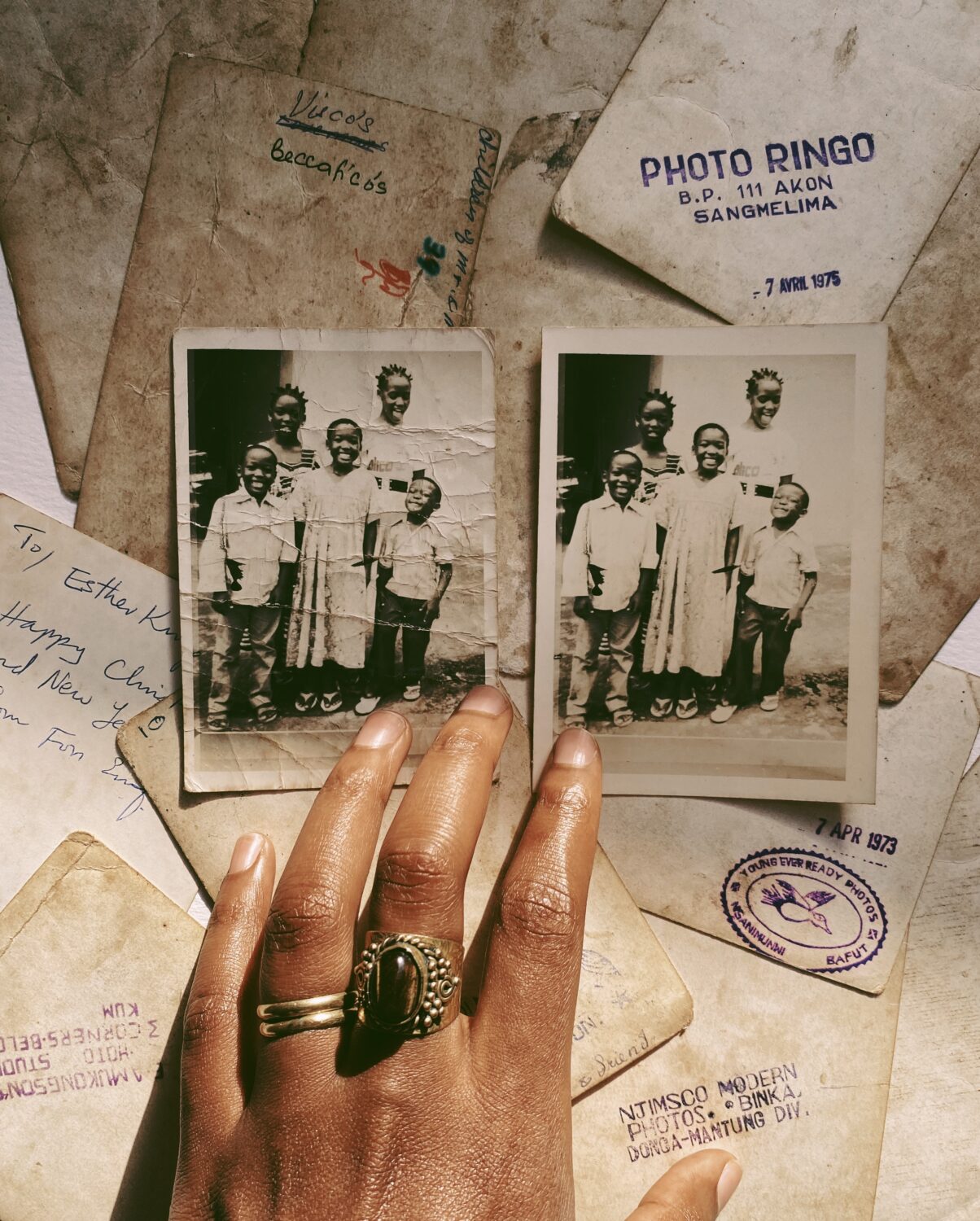

ET: Image Frequency Modulation (IFM) began as a lockdown project. I had time to sit with my family albums and get lost in stories my dad would share in fragmented bits, which I started to record. I then started finding other material such as postcards, letters, and a book of proverbs he edited a while back. I became obsessed with this material and experimenting with ways to preserve these visual, sonic, and haptic encounters I was having, in order to build a future archive of sorts. The project is very much informed by Black feminist theorist Tina Campt’s work, with her book ‘Listening to Images’ being my entry point into her radical modes of inquiry. IFM responds to these ideas in an ongoing iterated body of work, investigating the frequencies of images. It is concerned with ancestral memory and transmission. Frequency modulation, or FM as popularly known in radio, is the encoding of information in a carrier wave. Frequency is also not just a temporal interval or kinetic cycle, but also a vibrational sound which I explore through sensory installations. I am now developing the second iteration of the project which especially expands on the sonic and the Black interior.

SC: How have you gone about gathering material? I’m curious to understand more about the process of selection.

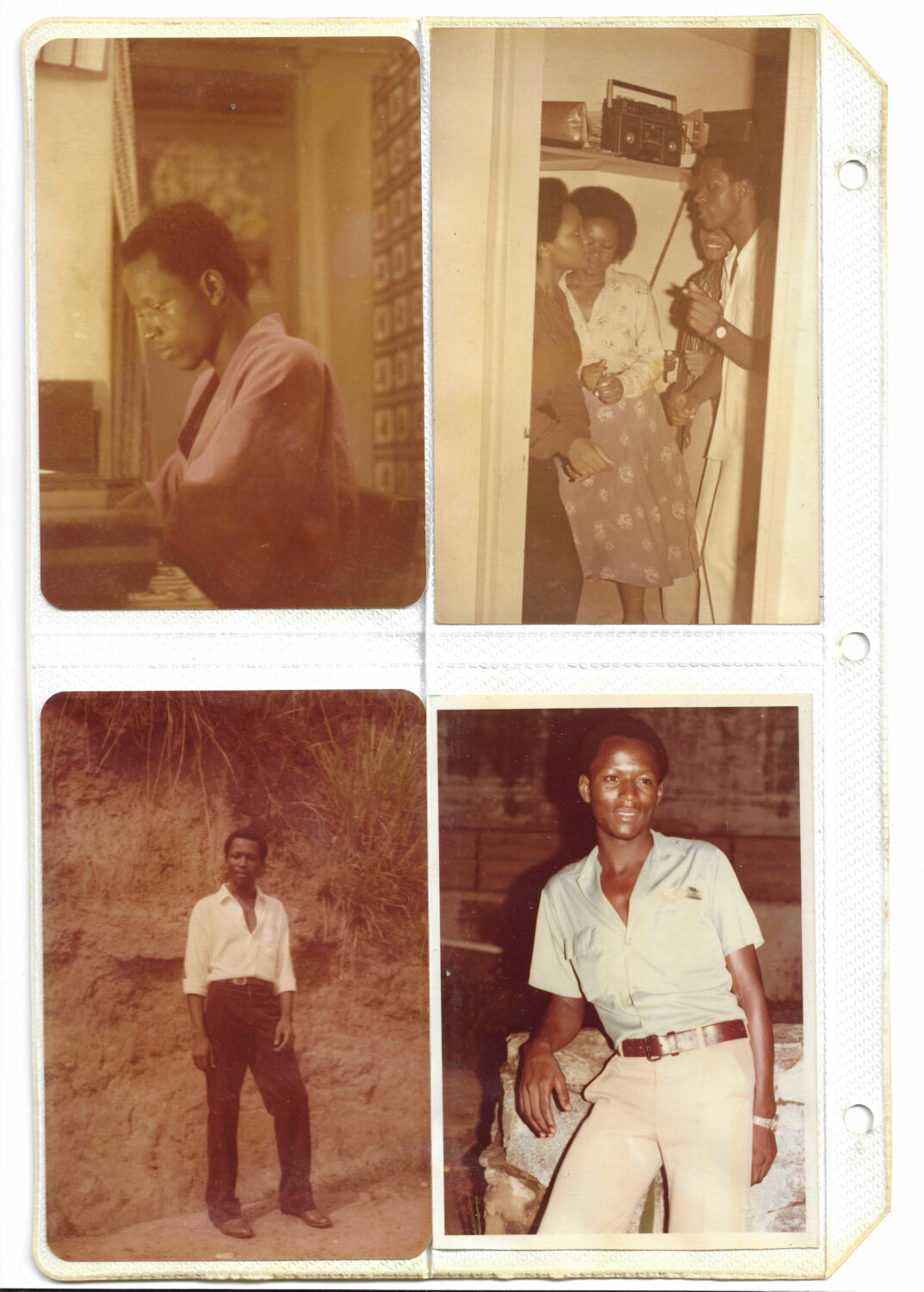

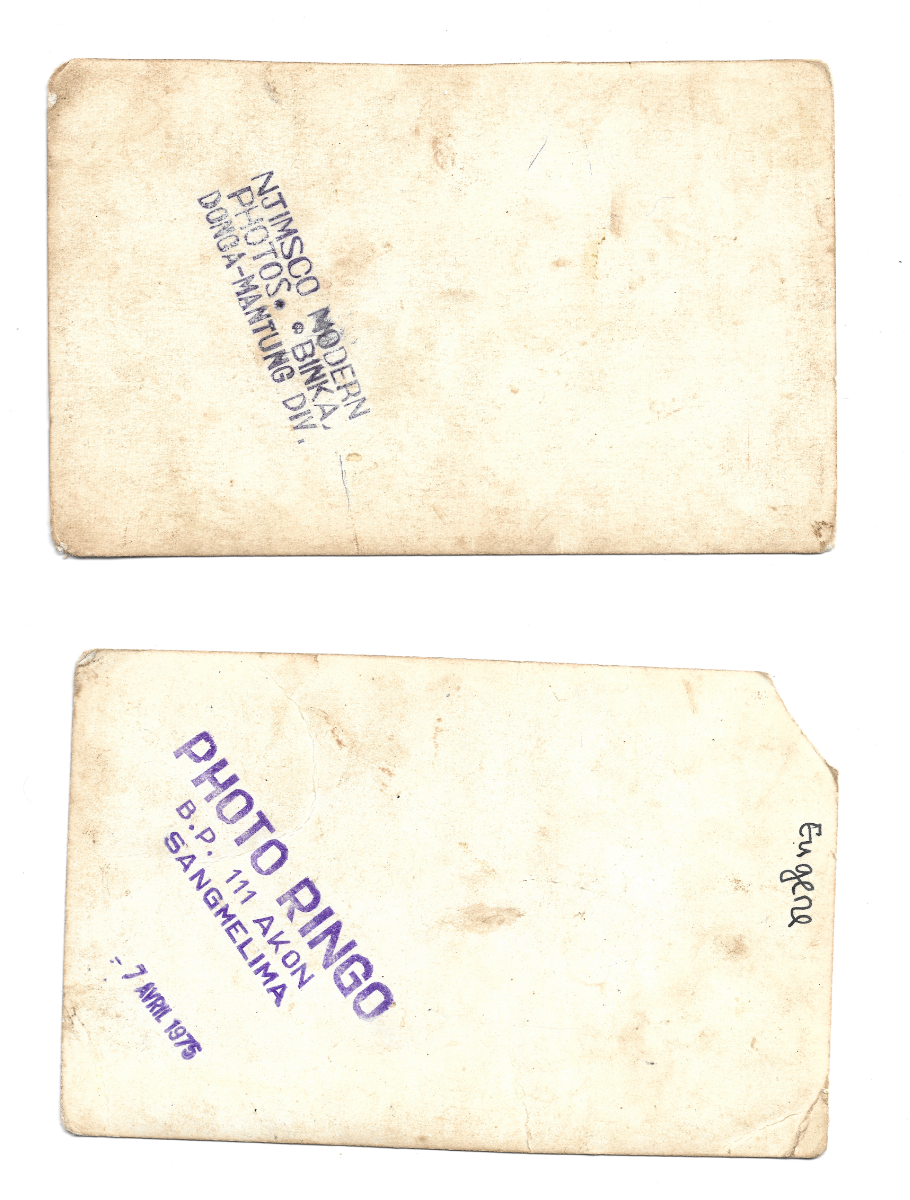

ET: It’s really an intuitive process. I don’t have a ‘clinical’ background in archiving although I was exposed through my mother’s work as a librarian/archivist when I was younger. It feels like such a circular moment to recognize how much of my practice (and this project in particular) marries both my parents’ early careers; my dad as an interpreter and a radio host in his younger years. Family photographs can act as a portal into memories and moments we forget or may have missed. Looking through the material, I’m reconnecting with my grandparents, I’m reading annotations on the back of the photographs, I’m learning about what studios were popular in the different regions my family lived, I’m connecting with strangers and I’m listening closely. One of my favourite quotes by Ariella Azoulay is: “the event of photography is never over. It can only be suspended, caught in anticipation of the next encounter that will allow for its actualisation.” Gathering sound has also been intriguing for me and I’m excited to focus on a collaborative approach in this second iteration.

SC: Could you expand on your interest in the sonic, visual and haptic frequencies of photographs?

ET: In the first iteration of IFM, I reactivated my father’s photographic archive by interlocking and layering memories of past and present. In the process, I examined my father’s notable relationship to sound as an interpreter, radio host, and storyteller throughout the course of his life and career. We recorded proverb recitals which he taught/passed down to me. In the research and making of this work, I started to recognise and reframe memory as a present experience rather than a past, while montage and assemblage became modes of memory-making in the first installation. I continue to examine Campt’s notion of ‘haptic images’: how we touch and are touched by images. What became really interesting to investigate in relation to my family photographs, was their circulation to me, the stories passed down through oral tradition, and their ability to reactivate memory. The sonic, visual and haptic kept recurring.

SC: You have very recently commenced a month long residency at Palm Heights, Grand Cayman — are you able to tell us about your plans there?

ET: Yes, it’s really exciting to be in this part of the world. I have spent some time in Cuba before which is nearby but it was important for me to finish this journey through what I’m calling a ‘Black Atlantic constellation’, which I’ve been charting through lived experience. From my home in Cameroon, to East Africa, Europe, the US and now here in the Caribbean. I’m thinking of figurative ‘radio technologies’ that tie these places together across time. Palm Heights has the beautiful Library Fetish space whose books I’ll be digging through and developing the sonic component of Image Frequency Modulation. I’ll also be developing this series here on Something Curated, documenting the phases. I started with curating the first Image Frequency Modulation playlist on Apple Music and Spotify which captures the project’s essence and feels like a soundscape to the process. It includes sounds that resonate across the African diaspora, from acoustic drums to electronic immersions.

SC: Concurrently, you are working closely with Magnum Photos — how does this tie in?

ET: The second iteration of Image Frequency Modulation is supported by the Magnum Foundation’s Counter Histories Initiative. It’s been incredible to have their support through project development workshops, cohort sessions, and the grant. I’ve always been invested in the idea of ‘counter histories’ when dealing with Black archives because of the many gaps that exist. I’m interested in attending to those gaps and thinking about questions like: What potentials lie in the family photo album? What does it mean to inherit and care for these images? When does a private family heirloom become a public work of art?

Listen to the Image Frequency Modulation playlist on Apple Music and Spotify.

Feature image: Image Frequency Modulation (2021), Ethel Tawe. Twin pocket photographs of father, circa 1973.