How The Ingenuity Of Korea’s Hanok Helped Shape Modernist Architecture

By Something CuratedThe hanok is a traditional Korean house that was first designed and built in the 14th century during the Joseon dynasty. Historically, traditional Korean architecture paid great attention to the positioning of the house in relation to its surroundings, rooted in a principle called baesanimsu, which considers the optimal home to be built with a mountain behind it and a river at the front. With much thought given to living in harmony with the landscape and climate, this long-established form of architecture is inherently environmentally conscious; the raw materials used in the construction of a hanok, such as soil, timber, and stone, are all natural and recyclable, with an aim to minimise pollution.

Carefully considered to withstand the sharply changing seasons, hanok are fitted with meticulously tiled roofs, known as giwa, bolstered by wooden beams and stone-block construction. The edge of the curved roofs, known as cheoma, can be adjusted in length to control the amount of sunlight that enters the home. The hanok’s structural posts, or daedulbo, are not inserted into the ground, but are instead pragmatically fitted into the building’s cornerstones to keep the hanok safe during earthquakes. A form of traditional Korean paper called hanji, coated with bean oil to make it waterproof and polished, is used to make breathable windows and doors.

A distinctive feature of the hanok is its resourceful design for cooling the interior in summer and heating it in the winter. The ondol, a floor-based heating system, and the daecheong, a cool wooden-floor style hall, were devised long ago to help Koreans survive the frosty months and to block out excessive sunlight during summer. These early types of heating and air-conditioning were so effective that they are still in use in many homes today. While American architect Frank Lloyd Wright was posted in Japan during the design of the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, he came across the ondol system, which was adopted from a Korean palace by the Japanese during the colonial rule of Korea.

Wright was so struck by this method that he integrated the system into the Jacobs House, which he had constructed in Wisconsin. The modernist pioneer went onto apply similar temperature controlling systems in the Usonian houses he designed in the 1930s in the USA for middle class families. As well as including the ondol system, the homes he designed featured floor to ceiling windows, bringing nature into the properties’ living spaces. Borrowing another vital philosophy of the hanok, the interconnected bedrooms were made intentionally small to prompt inhabitants to spend more time together in the larger open plan spaces.

Later, another modernist fascinated by Eastern design, German-American architect and furniture designer Ludwig Mies van der Rohe conceived the celebrated Farnsworth House, completed in 1951. The house effectively blurs the boundaries between the exterior and the interior. A similar approach can be identified in the hanok of the southern regions of Korea, where, due to high temperatures, homes were built with rooms arranged in a straight line in order to allow for optimal air circulation, with uninterrupted living space and vast windows. In recent years, the hanok has seen a revival of sorts in Korea, with an increased interest in old ways of living. And further afield, the essential principles of this traditional home continue to influence the development of contemporary architecture.

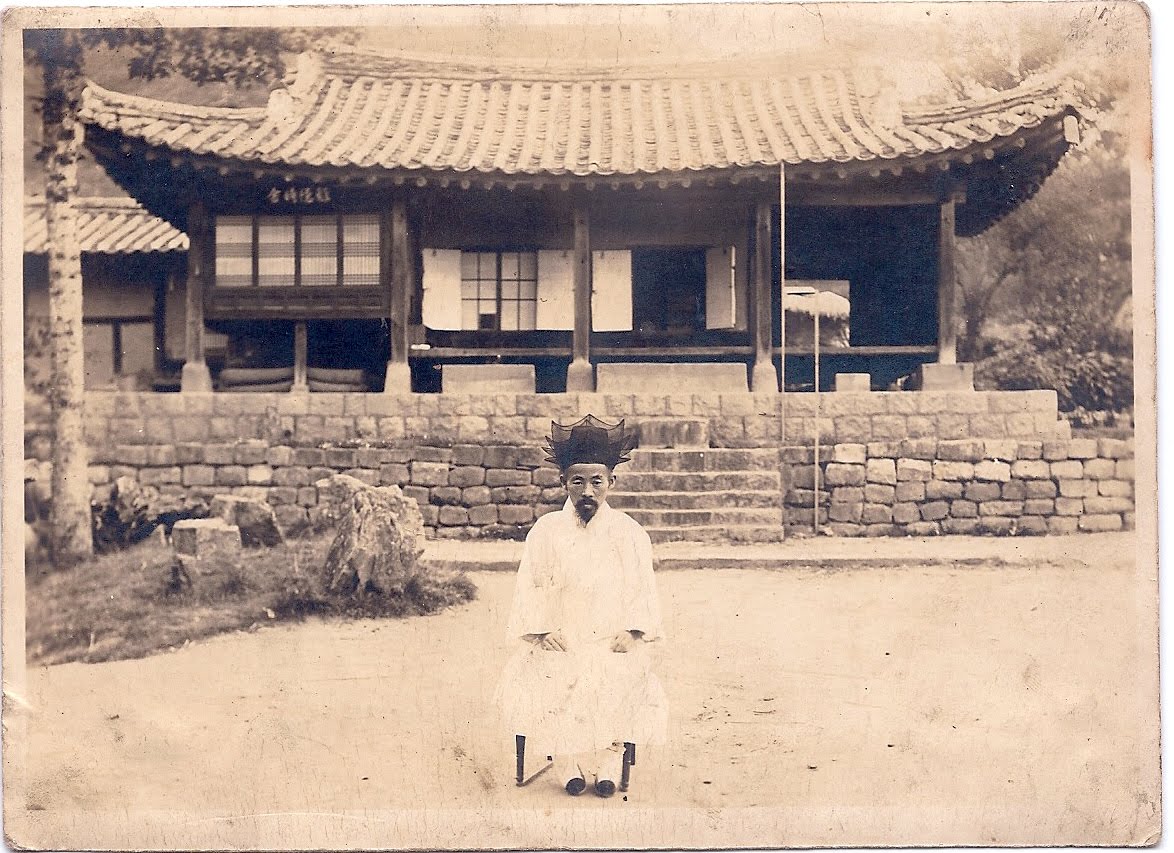

Feature image: 한국의 집, 한옥, 1709-2013. Photo: JO SanKu