Is The Kama Sutra The Most Misunderstood Text Of All Time?

By Keshav AnandGaining notoriety as an illicit manuscript during the colonial era, when the British Raj controlled the Indian subcontinent, the Kama Sutra’s prevailing image has long been sexually explicit. Synonymous with carnal contortions, it first raised eyebrows in a time characterised by sexual censorship. But this multifaceted work encompasses so much more. The text proposes a guide to life, delving into topics from self-awareness — understanding one’s own body and, later, that of a partner — to the pursuit of emotional connections and the institution of marriage. Concepts of wellbeing, adultery, the uses of herbs and the effects of aphrodisiacs, among other subjects, are all creatively broached. At its core, the Kama Sutra puts forward a psychological discourse, investigating the impact of desire and pleasure on human behaviour.

An anthropological study of sorts, the extensive manuscript gives us a glimpse into a prosperous and, at least in part, open-minded society of ancient times. Many historians believe the text dates back to the 3rd century, though the precise dating of the Kama Sutra remains a mystery. Indian philosopher Vātsyāyana, who is thought to have resided in the ancient Indian city of Pataliputra, today known as Patna, is widely considered to be the work’s author. Vātsyāyana’s Kama Sutra is organised into seven distinct sections, comprising 1,250 verses spread across 36 chapters. Written in a complex and obscure form of Sanskrit, translating the ambitious work has posed a lot of challenges, leading to many interpretations, and unsurprisingly, misinterpretations of the text.

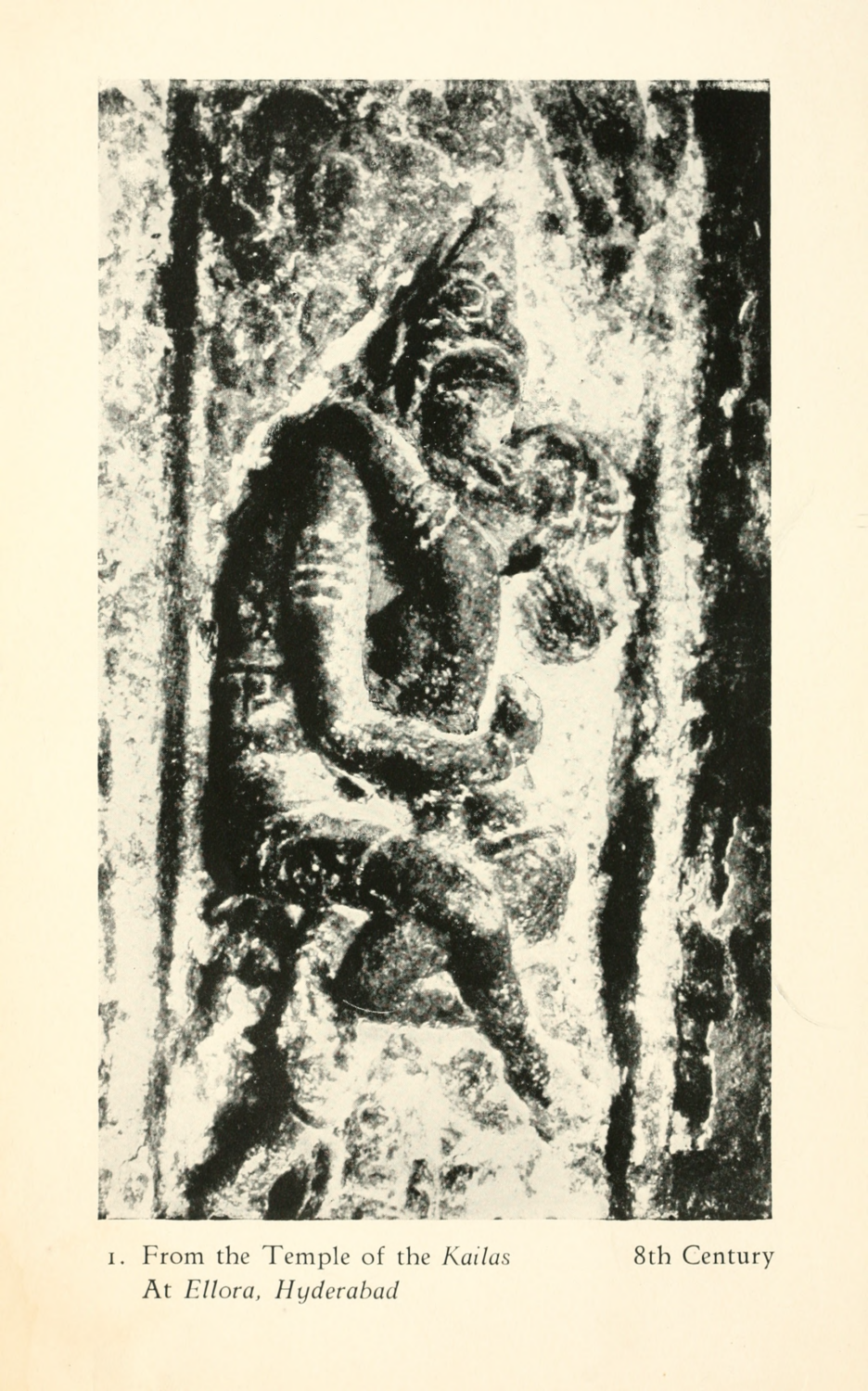

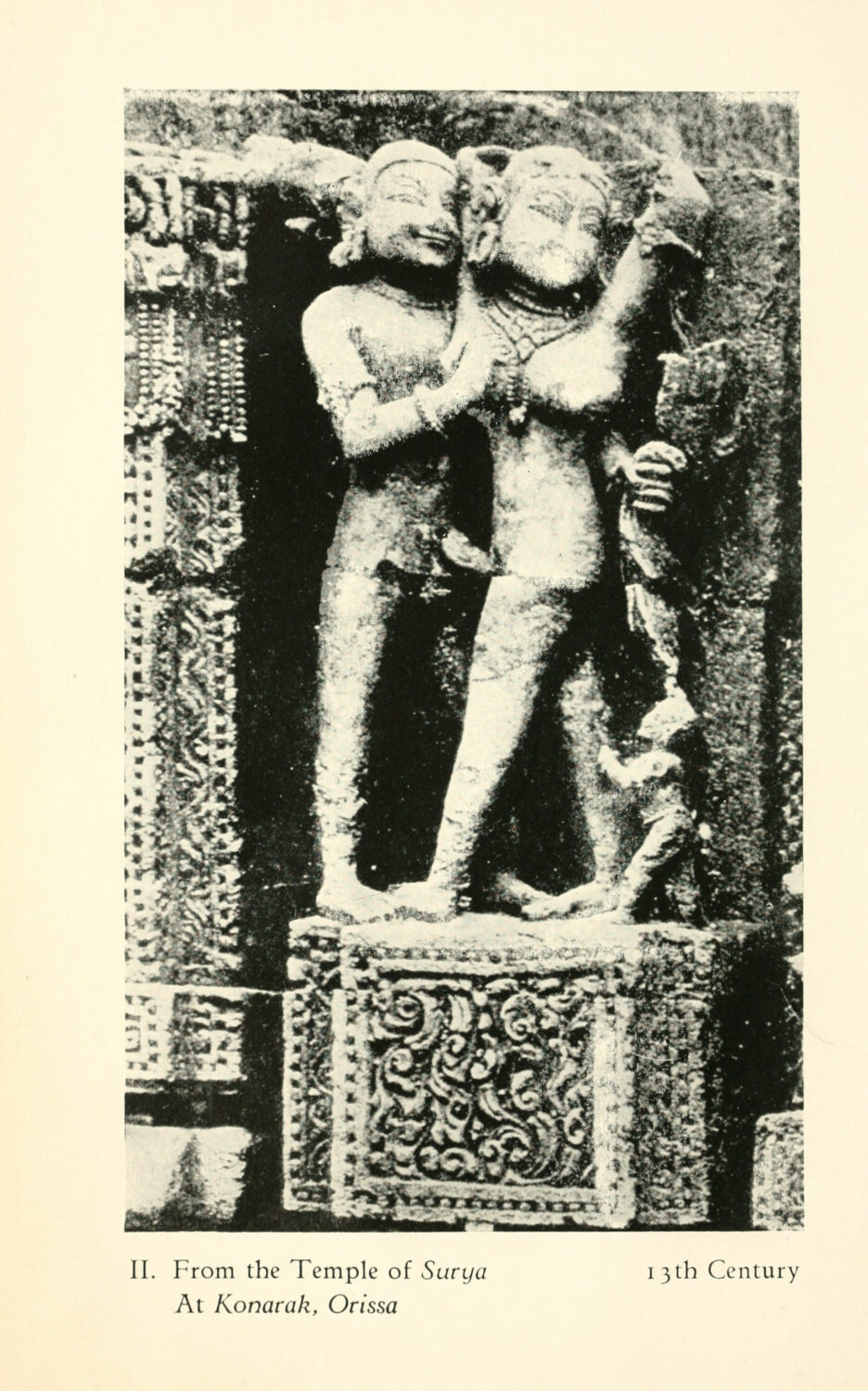

It employs a blend of prose and poetry, presenting its narrative in the form of a dramatic fiction featuring two characters known as the nayaka (male) and nayika (female), complemented by figures referred to as pitamarda (libertine), vita (pander), and vidushaka (jester). The teachings and dialogues within the text heavily draw upon ancient Hindu mythology. And contrary to its association with elaborate drawings of sexual encounters, an idea particularly cemented in the West, the original Kama Sutra did not even include illustrations. When addressing matters of sexuality with words, it methodically examines the finest details, akin to a forensic analysis encompassing everything from the alignment of bodies to the sounds emitted by participants.

Though authored from a male perspective, often promoting patriarchal values, some scholars have identified feminist elements within the text. Indologist Wendy Doniger argues that the Kama Sutra is a bold work advocating a form of sexual liberation for women that would have challenged the sensibilities of contemporary puritanical censors. Throughout most of the text, Vātsyāyana disregards the concept of sex solely for procreation and instead prioritises the pursuit of sexual pleasure. This stance challenges the moral responsibilities of Hindus as prescribed in earlier writings about reproduction. Additionally, Vātsyāyana rejects principles that recommend penalties for women involved with men other than their husbands. The Kama Sutra also provides insights into women’s perspectives on ending affairs, presents surprisingly modern notions of gender, and maintains an open-minded stance on homosexuality.

Throughout the numerous centuries since its origin, the Kama Sutra became an integral component of the Indian literary canon, and during the Mughal Empire, the first recorded illustrated editions of the work were produced. However, the transition of this work from a piece of esoteric South Asian wisdom to a lasting fixture within worldwide popular culture, subject to endless republication, reinterpretation, and parody, can be largely attributed to the endeavours of Sir Richard Burton, a Victorian explorer and Orientalist scholar. Burton’s translation is now acknowledged as a greatly inaccurate interpretation, yet it was the depictions of sexual positions within his version that captivated the public’s interest — unsurprisingly. Releasing the Kama Sutra in the United Kingdom was an audacious move, considering the stringent Victorian obscenity laws in place.

To navigate the sensibilities of his era, Burton opted for a strategy where he had the book printed exclusively for private distribution, under the guise of a fictitious organisation known as the Kama Shastra Society of London. The book went onto become widely pirated but its global influence and repute exponentially surged when it was officially published in Britain and the United States during the 1960s, coinciding with the onset of the sexual and cultural revolutions that were sweeping through the West. While Western perceptions have often reduced the Kama Sutra to an exotic guide of sexual practices, this intriguing and comprehensive work is an anthropological undertaking, a philosophical treatise remarkably ahead of its time. With all its flaws, ultimately, the text’s objective was to propose a manual for life, positioning at its centre a pursuit for wellbeing and pleasure.

Feature image: Two folios from a palm leaf manuscript of the Kama Sutra text (Sanskrit, Devanagari script). 13th century. Photo: Wikimedia Commons