In My Kitchen: Joké Bakare

By Adam Coghlan and Michaël Protin

During the course of the last three years, Adejoké – Joké – Bakare has emerged as one of London’s most important chefs. Her restaurant brand Chishuru, which came to life in Brixton Market in 2021, after the chef won a competition, has helped to deepen the city’s understand of Nigerian cuisine, specifically, and West African culinary culture more generally. Initially operating as a supper club before the two-year residency in Brixton, Chishuru has evolved and now sits across a slick two-floor space in Fitzrovia, just north of Oxford Street in central London. In some ways, Bakare’s journey maps the trajectory of West African cuisine in the city and Bakare’s brilliant, idiosyncratic food has earned numerous awards and plaudits, helping to expand its audience and in doing so, bring it in from the fringes.

Chishuru 3.0 opened on Great Titchfield Street in the autumn of this year. It is the culmination of Bakare’s life journey to date, fulfilling a long held ambition: A modern London restaurant which tells the story of what she calls “true” West African food.

Here, in her own words, the chef discusses her journey and the importance of food throughout her life, through a collection of objects and ingredients she holds most dear.

Bust

This is a legendary woman in the old Benin Empire.

She stood for strength and commitment to family – and the reason I brought her is that it’s almost like a reminder of commitment to my family, commitment to my roots and the desire to be passionate about something so much – to the extent that you are willing to give everything.

That’s what this is: that passionate love for family, passionate love for the community.

Every time I look at it, especially when I’m not sure what I’m doing or I’m not sure how I am going…it’s almost like an assurance, a touch point for me to see that there are people who are willing to give so much for what they believe in. And there are always people who remember them.

Brixton Kitchen Award

I’d always wanted not just to have a restaurant but to be able to showcase my food in a different way and bring my food to a wider audience, but I never knew how to be able to achieve that.

Winning that competition [in 2020] almost coalesced all my thoughts about what it is that I wanted to do: it was an opportunity for all those things that were inside of me, all those things that I was writing, all the things I was practising – it gave me an opportunity to showcase it. It’s what sparked and what made Chishuru what it is, and what brought it to where we are.

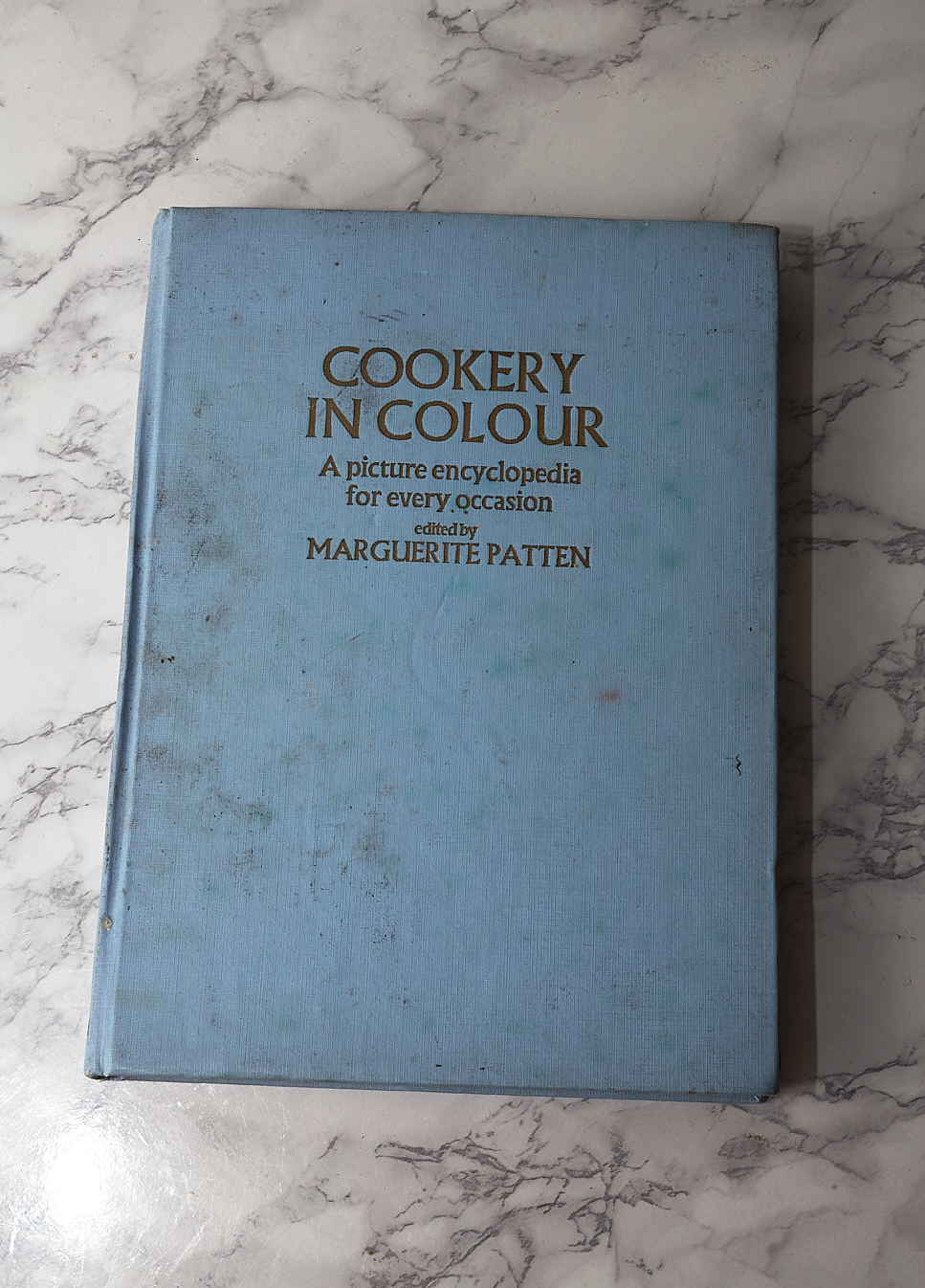

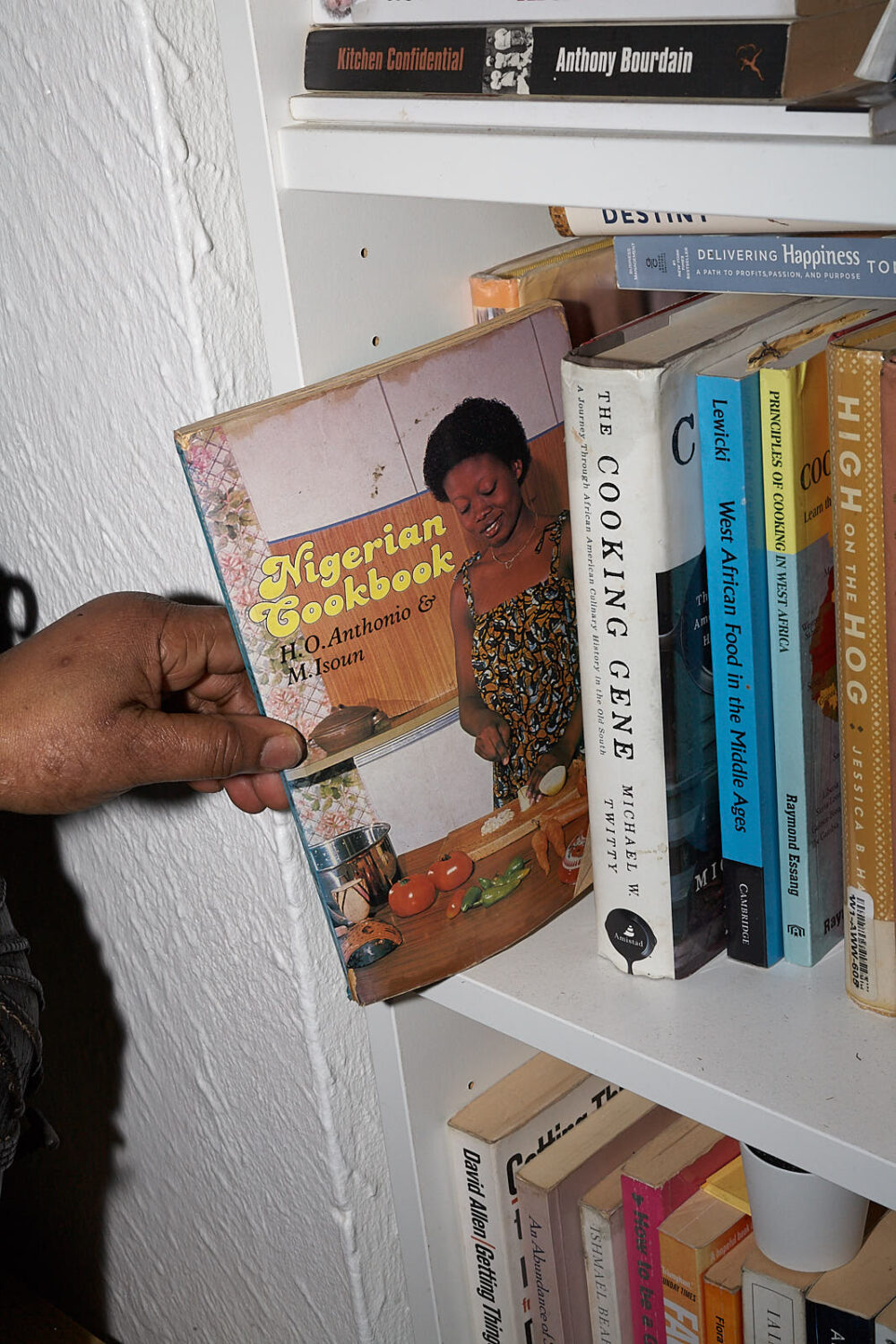

Cookbooks

Marguerite Patten’s Cookery in Colour.

I’ve had it for at least 35 years or more. A friend, or cousin of mine visited the U.K. for holiday – and I said to her, ‘just get me something, something you know I like.’ I’d always liked food, since I was young, I’d been curious about how things come together and she came back [to Nigeria] with this book. And even though at that time, there was a bit of difficulty finding some of the ingredients, it just fired me up – opened me up. Oh my god, cooking, and eating food from different places gives you a connection to that place. Food for me has not always been only about sustenance; it’s been about adventure, knowing, discovery. That opened me up.

My very first cookbook that I bought immediately after the Margaret Patten one, The Nigerian Cookbook.

There’s not a lot of representation of Nigerian food, of West African food in cookbooks, because we don’t document our food so much. We don’t write about it; most of the recipes are word-of-mouth, or people just learn by watching.

This was one of those books which at that time was the closest thing to authentic recipes as you could get and both books started me off on my lifelong ambition to collect books and cook.

Mortar

My dad always said that there are some sauces that are best when they are blended by hand and if you can’t get the stone grinder, the next best way is to get the mortar. There are sauces that only taste the exact way they’re supposed to taste when it’s been muddled in a mortar.

This one is from the Queen’s market, in East London.

It says something about me and the way I cook, whereby I am able to use what it is that I’ve got available to me – because of where I am, and I can’t necessarily get all the spices, the ingredients, the things that I need. So I try and adapt. In many ways the mortar [represents] my adaptability.

Ogiri

These are the fermented ingredients we use in the restaurant: fermented fresh water fish, the paste of fermented castor bean, gourd seeds – it’s the umami base to so much of our cooking.

The thing with a lot of Francophone West African food is that it’s always wanted to be French; and with Anglophone, we’ve wanted it to be more English. With Chishuru [and with these ingredients], we are moving back towards the true West African food.

Spices

These are the basis: Our food is not complete without this selection of spices; using them all means we are able to tell the true story of our food. If you take these out, then you take the soul out – then it can be anyone’s food.

Photography by Michaël Protin. This interview has been edited for clarity.