What is Mingei?

By Róisín InglesbyMingei, the influential folk-craft movement that developed in Japan in the 1920s and 1930s, is the subject of William Morris Gallery’s upcoming exhibition, Art Without Heroes: Mingei. With more than 80 works on display — including ceramics, woodwork, paper, textiles, photography and film — the presentation will incorporate unseen pieces from significant private collections, along with museum loans and historic footage from the Mingei Film Archive. Ahead of the opening on 23 March 2024, William Morris Gallery Curator, Róisín Inglesby, shares with Something Curated her expert insights on the movement. The below are her words.

What is Mingei?

That depends on who you ask! Officially, Mingei is a term coined by philosopher Yanagi Sōetsu and his associates in the 1920s, to describe everyday, useful, handcrafted objects, produced by anonymous makers. It is a shortening of minshūteki kōgei meaning ‘crafts for ordinary people’, or ‘folk craft’, that Yanagi admired for its traditional manufacture and aesthetic purity.

However, the term quickly became associated with the more educated, urban practitioners involved with the Mingei movement, rather than the folk craft objects themselves. Today we have even more flexible definitions, which vary between Japan and overseas. So it’s always been pretty subjective, which is one of the things that makes it interesting.

For me, the question of anonymous making is hugely compelling. Yanagi and other Mingei theorists believed that truly beautiful objects could only be made by unknown makers, who were creating things by constant repetition, on a level beyond the individual ego. This relates to the Buddhist idea of mushin, or freedom from mental attachment, and in a positive sense this ties into ideas of meditation and mental liberation through making that sound very attractive.

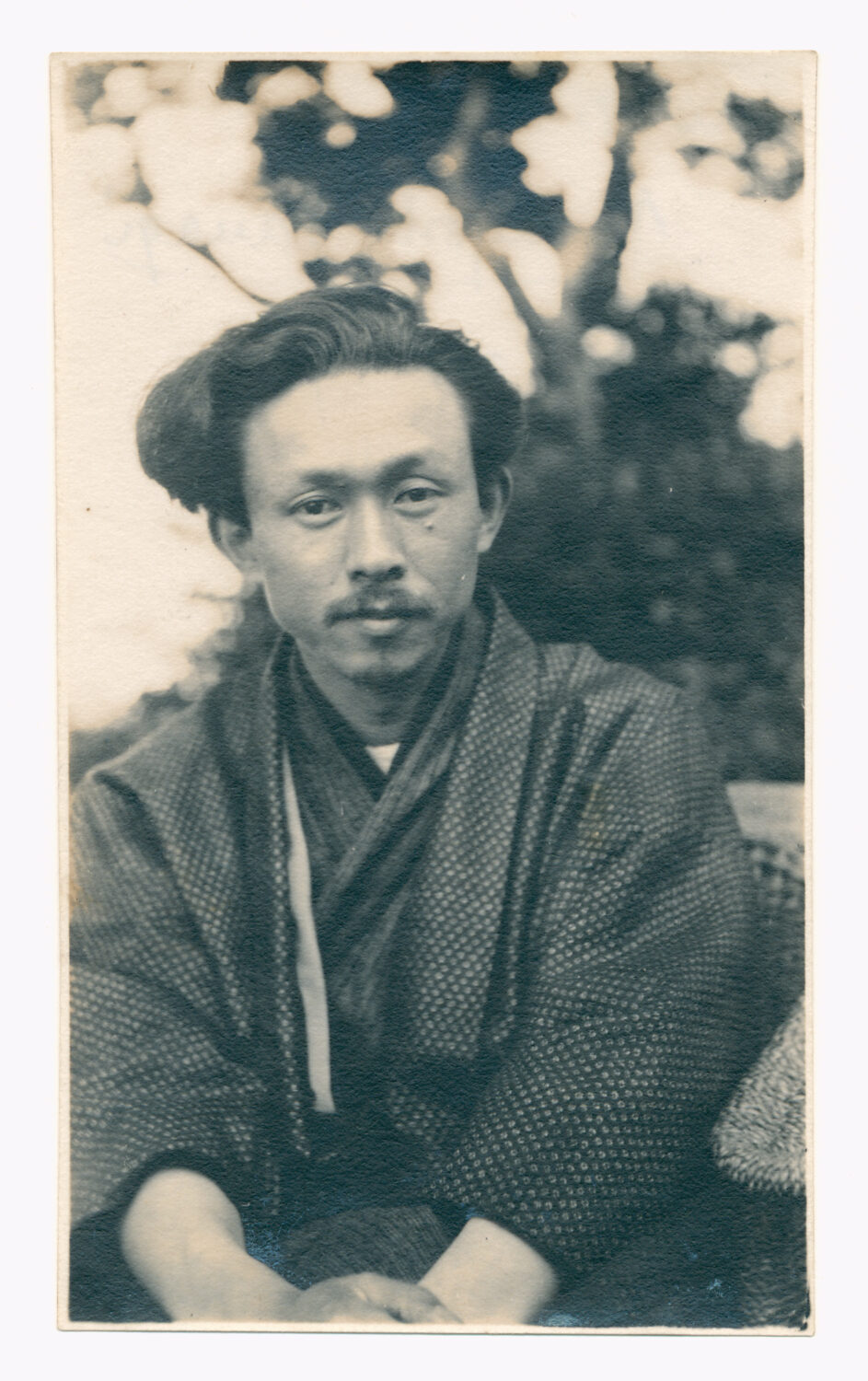

On the other side, this kind of unacknowledged, repetitive, poorly paid labour can feel very exploitative, and the situation is made more complicated by the fact that the potters we associate with the Mingei movement, such as Hamada Shōji, Kawai Kanjirō, and Bernard Leach, became very famous. So this is where the Idea of Art Without Heroes comes in — what is the role of the individual in the creative process?

Curating Art Without Heroes at William Morris Gallery

There is a fairly common misconception that Mingei is all about ceramics — not surprisingly as most of the practitioners involved with the movement were potters — so I have tried to show a balance of media, especially textiles which are some of the most extraordinary examples of Japanese folk craft. To some extent I’ve been guided by what Yanagi thought of as Mingei — for example sashiko stitching and Ontayaki pottery — but I have also challenged his definitions, particularly with the inclusion of boro textiles, which although very Mingei-like to us, were considered too associated with poverty.

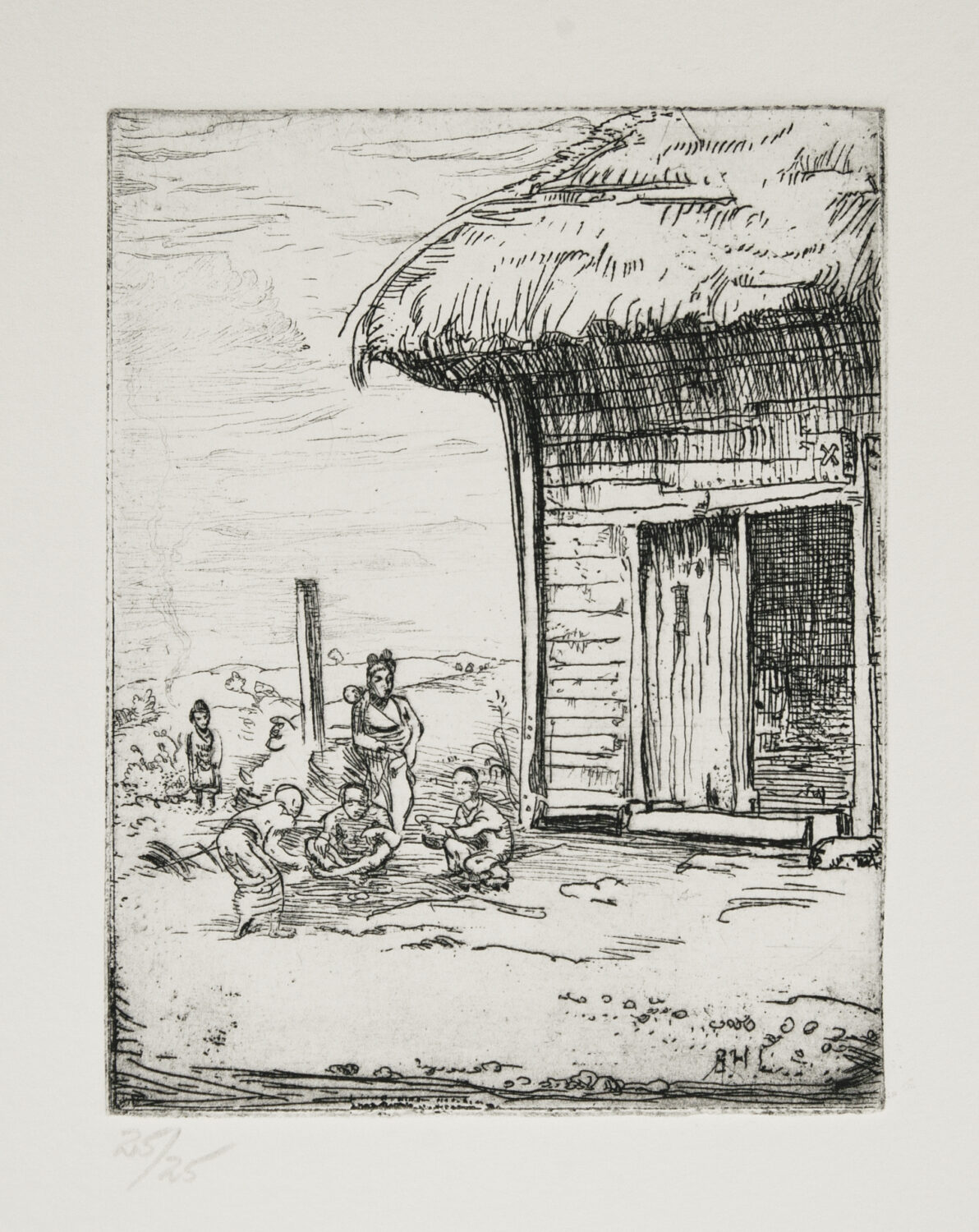

I also wanted to include objects from Korea, Okinawa and Ainu makers in Hokkaido — areas recently colonised by the Japanese at the time, to show how significant these were in defining the aesthetic. The Ainu objects have been chosen in collaboration with Ainu artist Mayunkiki, as it was very important for me to include greater representation in selecting and interpreting these pieces.

Alongside work by the more famous Mingei ‘heroes’ such as Hamada Shōji and Serizawa Keisuke, I’m really delighted to show work by lesser-known makers, particularly a vase by Sardar Gurcharan Singh, an Indian potter associated with the movement who has only recently become part of the Mingei story.

I’m also thrilled to have a teapot painted by Minagawa Masu, especially as we also have brilliant footage of her at work, part of the Mingei Film Archive, which really adds great atmosphere and context. And it’s very exciting to have pieces by Theaster Gates, whose Afro-Mingei work forms an important dialogue with the exhibition’s wider issues around anonymous making and representation within craft practice.

Mingei today

I spent three weeks In Japan last year researching what Mingei means today, and it’s so interesting to see the various legacies. For some people it’s still associated with the movement itself, so it’s more of a historical legacy, preserved through the Japan Folk Crafts Museum (Mingeikan), which Yanagi established in the 1930s. In Mingei’s affordability, utility and anonymity, there’s also a lot of crossovers with the world of design; Yanagi’s son Sōri and Fukasawa Naoto, respectively the former and current director of the Mingeikan, are both known for their product design.

Elsewhere, you can see Mingei ideas in small craft startups and ecologically-conscious production — young people leaving urban lifestyles to make things in a more sustainable way, which is of course exactly what Hamada did when he founded his pottery in Mashiko. In many ways I feel Mingei is such a rich topic, and Yanagi’s writings are so varied that many people take different things from it, in a similar way to the life and work of William Morris.

Art Without Heroes: Mingei runs at William Morris Gallery, London from 23 March to 22 September 2024.

Feature image: Hamada Shōji demonstrating at Scripps College, California, 1953. From the collections of the Crafts Study Centre, University for the Creative Arts