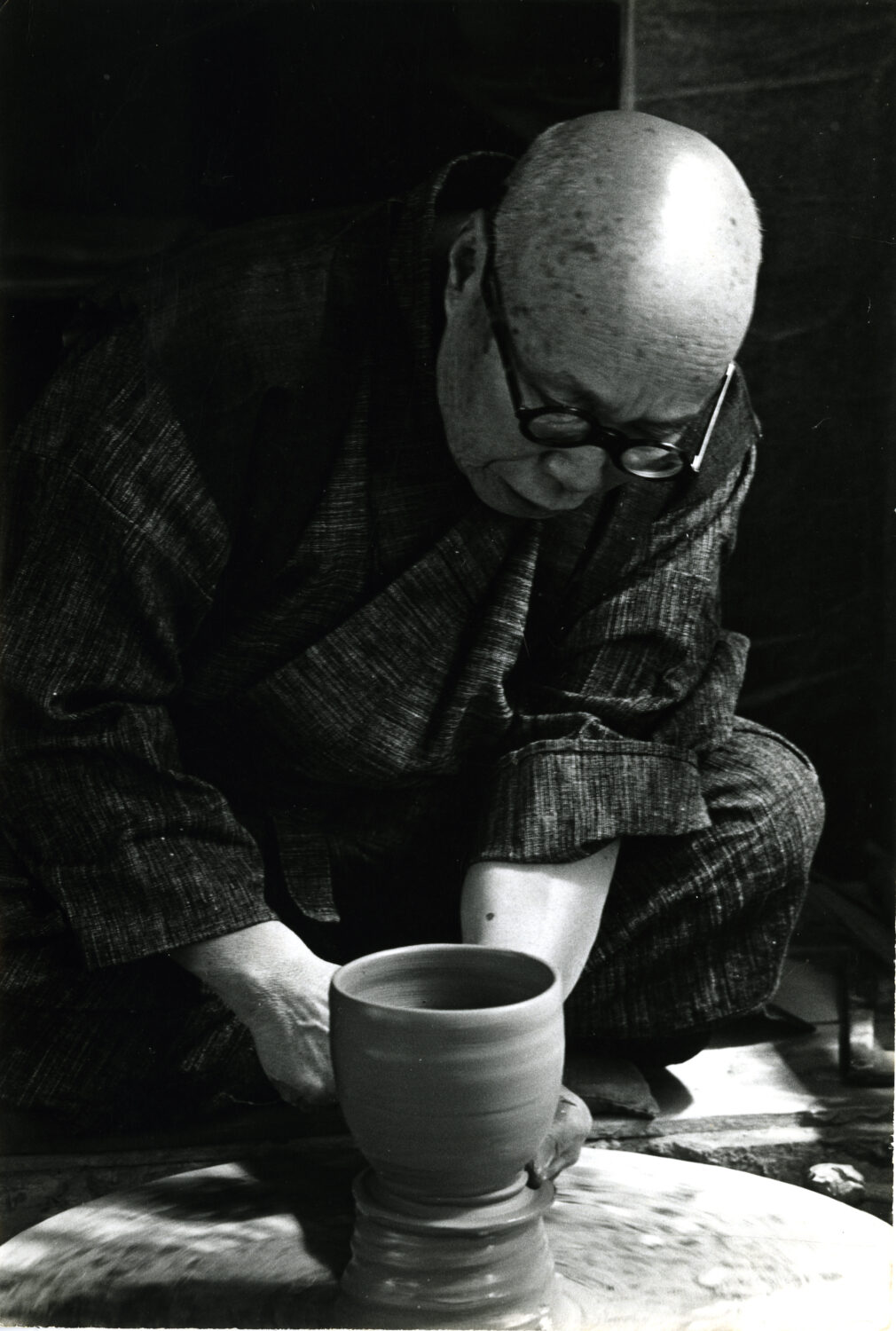

How Potter Shōji Hamada’s Visit To Rural East Sussex Shaped The Craft Movements Of Britain & Japan

By Something CuratedBorn in Tokyo in 1894, celebrated potter Shōji Hamada was a key figure in the Mingei Japanese folk-art movement, developed from the mid-1920s in Japan by philosopher and aesthete, Yanagi Sōetsu. Some years prior to the movement’s emergence, in 1921, a young Hamada travelled with his close friend and fellow potter Bernard Leach to the village of Ditchling from St Ives in England. The Japanese potter’s germinal visit to this tiny village in East Sussex went onto shape the course of the craft movement in both Britain and Japan in a profound way. Opening at the Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft on 22 October 2022, the exhibition, Shōji Hamada: A Japanese Potter in Ditchling, focuses on the cultural exchange between the East and the West at this key moment in the emergence of the studio pottery movement. On display will be over 70 ceramics, including 25 pieces by Hamada. To learn more about Hamada’s instrumental practice and its critical role in the cross-cultural exchange between Britain and Japan, Something Curated spoke with Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft Director, Stephanie Fuller.

Something Curated: Why is Shōji Hamada an important figure in the cross-cultural dialogue between Britain and Japan?

Stephanie Fuller: Shōji Hamada was hugely important to the development of the studio pottery movement both in his native Japan and Britain, and his influence spread worldwide. He was a founder of the Mingei movement in Japan – a folk craft revival which sought to preserve traditional craft skills whilst creating new modern work. This had strong synergies with the craft community in Ditchling, where Hamada forged a relationship with weaver and natural dyer Ethel Mairet who he visited several times in the 1920s, and whose work he exhibited in Tokyo as an example of excellence in this kind of approach. Indeed he was so impressed with her work and that of the weaver Valentine KilBride, part of the Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic, that he bought large quantities of fabric from them to sell in Japan, and also had a number of suits made of tweed produced in Ditchling, one of which he wore when he got married.

There was a shared concern in East and West about the impact of factory production and mass manufacturing on traditional craft skills. The emphasis on ‘truth to materials’ and design with a simple aesthetic played a prominent influence in the development of the Mingei movement as well as being the aim of the craft community in Ditchling. This concern was shared with Leach and they both travelled widely lecturing on this subject. Hamada’s work was successful in British artistic circles, already receptive to ‘Oriental’ art, and he had his first solo exhibition in 1923 at London’s Patterson Gallery. This was the first exhibition of contemporary ceramics held in London’s artistic heartland of New Bond Street, and paved the way for later potters including Leach, William Staite Murray, Katharine Pleydell-Bouverie and Norah Braden.

SC: Can you expand on Hamada’s seminal friendship with Bernard Leach?

SF: Leach had spent much of his childhood in Japan, and later returned to teach etching. However he became enamoured of pottery, and trained in ceramics. Moving in circles interested in Mingei and craft revival, he met Shōji Hamada who became a lifelong friend. When Leach returned to the UK in 1920 to establish his studio in St Ives, Hamada came with him to offer support on both the technical and artistic approach, and together they built the first Japanese style climbing kiln in the West. Leach later visited Hamada many times in Japan at the pottery he set up in Mashiko, where you can still see the kick wheel he used, which was specially built as he was extremely tall and needed much more leg room than was standard. They both travelled widely, lecturing on Mingei and studio pottery, and their shared influence was the catalyst for the development of the studio pottery movement internationally. They remained friends all their lives, and Leach wrote a book, Hamada Potter, presented as a dialogue between the two ceramicists, exploring their aesthetics, techniques and mutual inspiration.

SC: What is the thinking behind the selection of objects included in the Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft’s upcoming exhibition?

SF: The exhibition at Ditchling will showcase works from our own permanent collection alongside pieces drawn from collections across the UK, showing the influences on Hamada and Leach of Korean and other traditional ceramics, alongside Hamada’s own work and that of his contemporaries in both Japan and the UK. Other works will provide a context for Hamada’s visits to Ditchling, the craft objects he saw in Ethel Mairet’s house and elsewhere, which had such a profound influence on him and his later decision to move away from Tokyo to rural Mashiko to establish his own studio practice. This includes work by Mairet and members of the Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic produced in Ditchling. We will also show prints by Yoshijira Urushibara made in collaboration with artist Frank Brangwyn, another Ditchling resident, who had taught etching to Bernard Leach and was a great Japanophile, collecting Japanese art and advising Japanese collectors on purchasing contemporary Western art. Finally, Hamada’s lasting influence on studio pottery will also be embodied in the work of his grandson Tomoo Hamada, now running the ceramic studio in Mashiko, and British ceramicist Jennifer Lee whose work, though very different in style is also strongly influenced by Japanese ceramic traditions.

SC: And what do you hope to achieve with the show?

SF: We want to raise the profile of Shōji Hamada’s visits to the Ditchling craft community in the 1920s, and to demonstrate the ongoing two way influence between East and West that resulted. Hamada’s experiences in Ditchling had a profound effect on him, and the later development of the Mingei movement in Japan, a narrative which is unfamiliar to many in this country, but well known in Japan.

Shōji Hamada: A Japanese Potter in Ditchling runs from 22 October 2022 – 16 April 2023 at Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft.

Feature image: Shōji Hamada at work. Courtesy the Hamada Estate.