A Movie Starring Mick Jagger, Salvador Dalí, and Orson Welles — Is This the Greatest Film Never Made?

By Something CuratedFollowing its release earlier this year, Dune: Part Two continues the science fiction saga directed and co-produced by Canadian filmmaker Denis Villeneuve. Having grossed over $700 million since its arrival in theatres back in March, Villeneuve co-wrote the screenplay with American writer Jon Spaihts, with plans for a third film already in the works — set to complete his adaptation of Frank Herbert’s 1965 epic novel, Dune.

Herbert’s seminal literary work has had an enormous influence on popular culture, with an impact spanning decades. It saw its first cinematic adaptation in 1984, brought to life by legendary filmmaker David Lynch. But there exists another attempt at adapting Dune that never made it to the big screen. Alejandro Jodorowsky, renowned for his films like The Holy Mountain and El Topo, once embarked on a 10-plus hour adaptation of Herbert’s novel that remains unrealised.

His ambitious concept included casting non-actors like Rolling Stones front man Mick Jagger and Spanish surrealist artist Salvador Dalí. An elaborate and very expensive art project, Jodorowsky’s proposal for the film sought to create a psychedelic and transformative experience for viewers — rather than subscribing to conventional modes of storytelling associated with sci-fi. The Chilean-French avant-garde filmmaker intended not just to adapt the book but, as he grandiosely put, to “change the public’s perceptions… change the young minds of all the world.”

From the very beginning, Jodorowsky’s project went big — ultimately to its detriment unfortunately. The visionary filmmaker rented a lavish castle for writing and enlisted Jean ‘Moebius’ Giraud, a celebrated French comic artist, to assist in storyboarding. Drawing more than 3000 boards and studies, the film’s opening shot borrows inspiration from Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil (1958). And for the soundtrack, Pink Floyd, fresh off their release of Dark Side of the Moon, were tapped.

Steeped in mysticism and superstition from the start, Jodorowsky assembled a team he called “spiritual warriors,” including Dan O’Bannon for visual effects, H.R. Giger to design the villains’ home planet, and Chris Foss, known for his sci-fi book covers and The Joy of Sex, to visualise the colossal spacecraft central to the film. Though never realised, the storyboarding of the project left a lasting impact on culture, influencing later works like Ridley Scott’s Alien.

Herbert’s 1965 novel follows the struggle for control over the desert planet Arrakis, also known as Dune. The teenage hero, Paul Atreides, leads armies and rides giant worms, making the adaptation an immense task in the pre-digital effects era. By the time $2 million of the $9.5 million budget was spent by Jodorowsky in pre-production, the film failed to secure further financing — perhaps unsurprisingly.

Jodorowsky’s reflections on this experience are fascinatingly and comically captured in the 2014 documentary, Jodorowsky’s Dune, directed by Frank Pavich. Jodorowsky attributes the project’s demise to its lack of “Hollywood” appeal, lamenting the movie industry’s preference for conventional narratives and fear of breaking boundaries.

Jodorowsky cast his son, Brontis, as the film’s protagonist, Paul, enrolling him in two years of martial arts training to prepare for the role. The eclectic cast also included Udo Kier and Orson Welles — the latter is said to have agreed to participate in exchange for nightly dinners prepared by the chef of his favourite Parisian restaurant. Another curious anecdote associated with the film that never was comes courtesy Dalí, who is supposed to have demanded a $100,000 hourly rate and a gilded throne made of entwined dolphins.

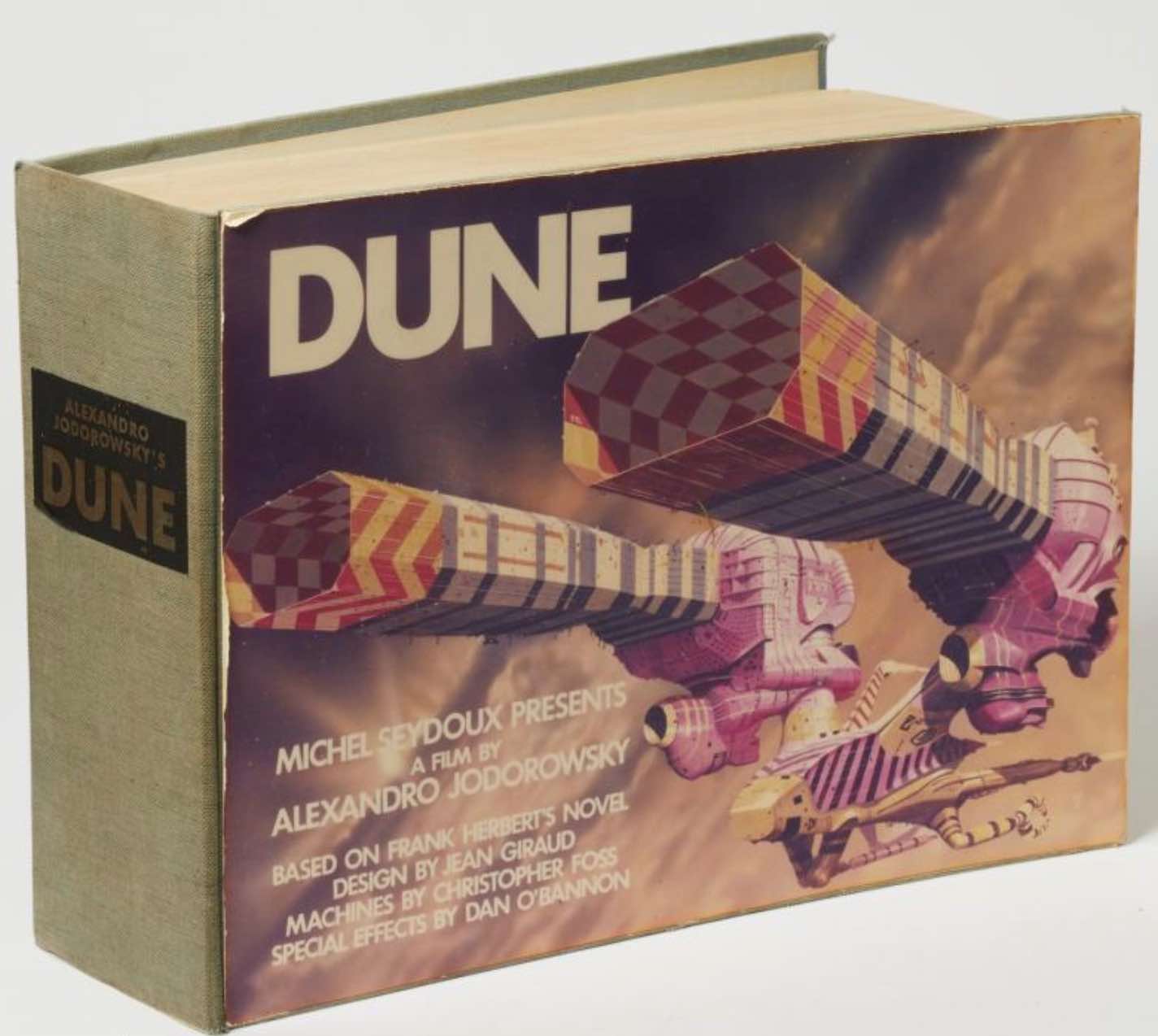

Despite the meticulous preparation, Hollywood studios balked at the film’s projected length and Jodorowsky’s unorthodox approach. In a final effort to secure funding, Jodorowsky and producer Michel Seydoux presented a detailed hardback book of the screenplay and storyboards, going from studio to studio in Los Angeles to pitch their ideas. However, their vision was repeatedly deemed unfeasible. Interestingly, shortly after their unsuccessful attempts came George Lucas’ first Star Wars film, a more commercially viable project that very much sits in the same world as Dune.

Feature image: A design sketch, by H.R. Giger, for the Harkonnen Castle as he envisioned it for Alejandro Jodorowski’s Dune. Photo: Pinterest