“Nostalgia Makes Even the Solitary Moments Seem Beautiful” — In Conversation with Japanese Sculptor Kenji Ide

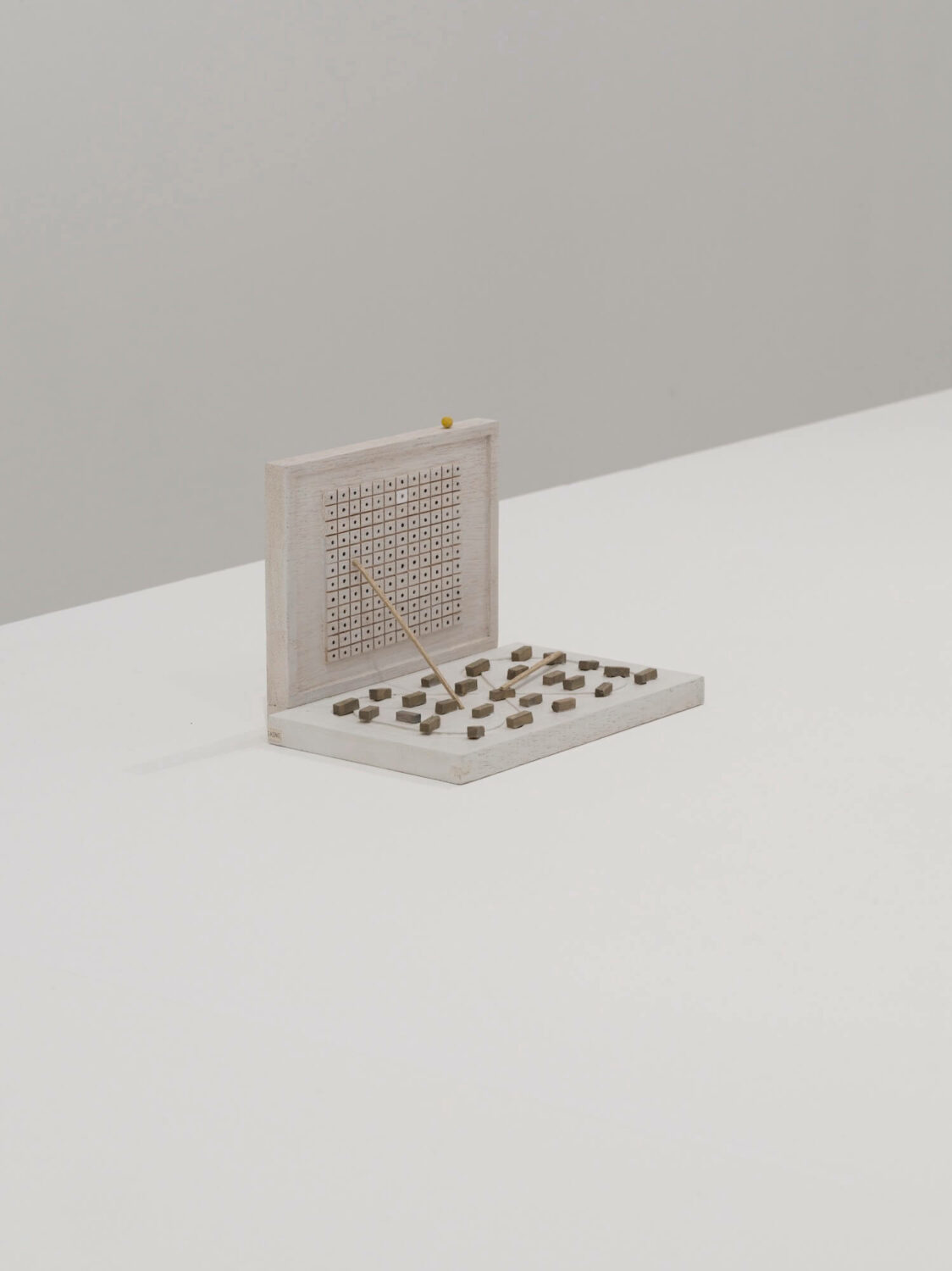

By Keshav AnandKenji Ide’s sculptural works, meticulously crafted from materials as varied as wood, paper, wax, stone, and concrete, alongside personal ephemera collected over the years, can be thought of as material poetry — odes to events in the artist’s life. Each component shapes the poem’s form, while their spatial arrangement establishes a rhythm.

Appearing almost like puzzles, Ide’s works aim to transform memories into something tangible, evoking multiple objects simultaneously. At once ambiguous and familiar, they allude to a purpose or logic but never quite make it clear. Ahead of the Tokyo-based artist’s solo exhibition at Władysław Broniewski Museum of Literature in Warsaw — presented in collaboration with Wschód gallery — Something Curated spoke with Ide.

Keshav Anand: What role does nostalgia play in your work?

Kenji Ide: Nostalgia makes even the solitary moments seem beautiful, especially when you are away from everyone and in pure and utter emptiness. To me, it is very important to remember yourself in this state, so that you can feel your existence at its richest.

Between the ages of 14 to 16, I’d sit by the sea near my parent’s house almost every day in the summer. I sat there expecting something sacred to happen, something out of a novel or religious text but, of course, nothing ever did. It was just me, the sunset on the horizon, and the view of the sea.

My work is rooted in these memories — this version of myself. It’s imbued with the sweet and sour taste of youth, and concerned with unchanging universal structures. The nature of human existence, especially humans in solitude, is my most recurring subject, but I try to permeate the work with a sense of nostalgia, so as to humanise it.

KA: Can you elaborate on why you refer to your works as “objects” rather than “sculptures”?

KI: I don’t mind the works being described as sculptures in English, but in Japanese I don’t call them “Chōkoku” which translates to sculpture. In Japan, the word Chōkoku is used within very limited contexts such as university sculpture departments. I don’t use it because I don’t belong there, and I’m hesitant about my work being described in such academic terms.

Conceptually and aesthetically, I also think referring to them as “works” fits much better. They are quite utilitarian, and can be equated with plastic bottles on the side of the road, a toy from Toys R Us, ancient crockery or traditional fittings.

Of course my objects take quite unusual forms, and have very personal elements to them, but what I’m saying is that I want to respect the fact that these are configurations of materials with an intention before they are sculptures or art objects.

KA: How do you choose the materials — such as wood, wax, or found items — for your pieces?

KI: Intimacy is a priority in the selection of materials, so I tend to choose materials that have had a presence in my own life and evoke the same feelings one might have for family and friends.

The lauan wood I use as the basic timber, for example, was a material I used to pick up from the big rubbish bins at school when I was a student. It was used to build temporary structures, so it was thrown away as soon as it had served its primary purpose. As such, it was easy to come by and there was always this feeling that I could take it back to my room and experiment. Then a lot of the smaller found objects in my work are things that I’ve found on the side of the road when walking with my own children and have therefore become very meaningful to me.

KA: How do you determine when an object is finished?

KI: My works are completed through the interplay of time and poetic sentiment. I usually start by creating a form or stage, and then assembling small objects on it. This process is comparable to a child playing with toys. I sense the work is nearing completion when it evokes a sense of time and memory that resonates with my own experiences. When I can incorporate my interpretation of the present into these expanded memories and experiences, I feel like a work is complete. The creative process is made up of a series of random ideas, existing in a space between desires, independent of the ego. So, the moment of completion is situated in an ambiguous space. Nostalgia is definitely a criterion for this judgment.

KA: What do you hope viewers take away from your exhibition at the Władysław Broniewski Museum of Literature?

KI: I hope that visitors’ experiences are deeply poetic. During my research on Władysław Broniewski, I became interested in the fact that his reputation snowballed so that he was this behemoth figure by the time of his death in 1962. I’m also very interested in the fact that Wilhelm Sasnal painted his portrait. Sasnal’s oeuvre has always been incredibly impressive to me, so I searched and watched Sasnal painting Broniewski’s portrait on YouTube. Perhaps it is my perversion, but I thought that Sasnal was trying to mar Broniewski’s elevated reputation and social image by depicting him as very human.

With Broniewski’s career trajectory in mind, this exhibition will see me explore my own experiences and emotions, especially with regard to the issues of loneliness, emptiness and success.

KA: Where are some of your favourite places to eat in Tokyo?

KI: Japanese food, as you know, is a cuisine that emphasises freshness in many ways, and amongst these I like buckwheat noodles. I often go to this soba restaurant called Shimizu in Chofu because it is in my neighbourhood, and its soba is highly aromatic and goes well with sake. The tempura is also fragrant with sesame oil, and the delicate freshness of the tempura spreads in your mouth!

KA: What are you currently reading?

KI: If I’m being honest, I rarely read books. But my favourite novelist is Rieko Matsuura. She has a lot of novels about women’s relationships, and I especially like her ‘Ura (Back) Version’. The book is structured as a short story, followed by a critique of the short story, and as the chapters progress, the critique threatens the short story, and the story shifts to a discussion of the human relationship between the person writing the critique and the person who is writing the short story. Her novels, while mediated by desire, are often a kind of experimentation with the body and mind, and are also very surreal, which allows us to think differently about human relationships.

Kenji Ide’s new solo presentation will run at the Władysław Broniewski Museum of Literature in Warsaw from 26 September to 26 October 2024.

Feature image: Kenji Ide, Two persons, two times, at KAYOKOYUKI, Tokyo. 14 January – 12 February 2023. Courtesy the Artist and KAYOKOYUKI, Tokyo