How the Aesthetics of the Islamic World Influenced Britain’s Arts and Crafts Movement

By Rowan BainThis autumn, William Morris Gallery in Walthamstow will present the first exhibition on the influence of art from the Islamic world on William Morris, one of Britain’s leading 19th-century designers and thinkers. A principal founder of the Arts and Crafts Movement, Morris was responsible for producing hundreds of patterns for wallpapers, furnishing fabrics, carpets and embroideries, introducing a new aesthetic into British interiors. Ahead of the exhibition’s opening, Rowan Bain, Principal Curator at William Morris Gallery, pens an essay for Something Curated exploring the influence of art from the Islamic world on Morris’s practice, and more broadly, on the Arts and Crafts Movement in Britain.

In 1882, the British designer William Morris lectured: ‘To us pattern designers Persia has become holy land, for there in process of time our art was perfected, and thence above all it spread to cover for a while the world, East and West’.

Morris remains a towering figure in British cultural history, recognised not only for his prolific contributions to design through his company, Morris & Co., but also for his socially progressive ideas on production, social equality, and the environment. His interests were wide-ranging, and from the 1870s, when he was in his forties, they included a deep engagement with art from the Islamic world.

Inspired by the work of art historian John Ruskin during his university years, Morris developed a lifelong respect for the craftsmanship of earlier eras. His engagement with Persian patternmaking, as outlined in the opening quote, was characteristically rooted in a romanticised view of the past. Morris never travelled further east than Italy and never visited a Muslim country. Instead, he gathered knowledge through literature and firsthand study of objects seen in museums, such as the South Kensington Museum (now the V&A), as well as in dealers’ shops and friends’ houses.

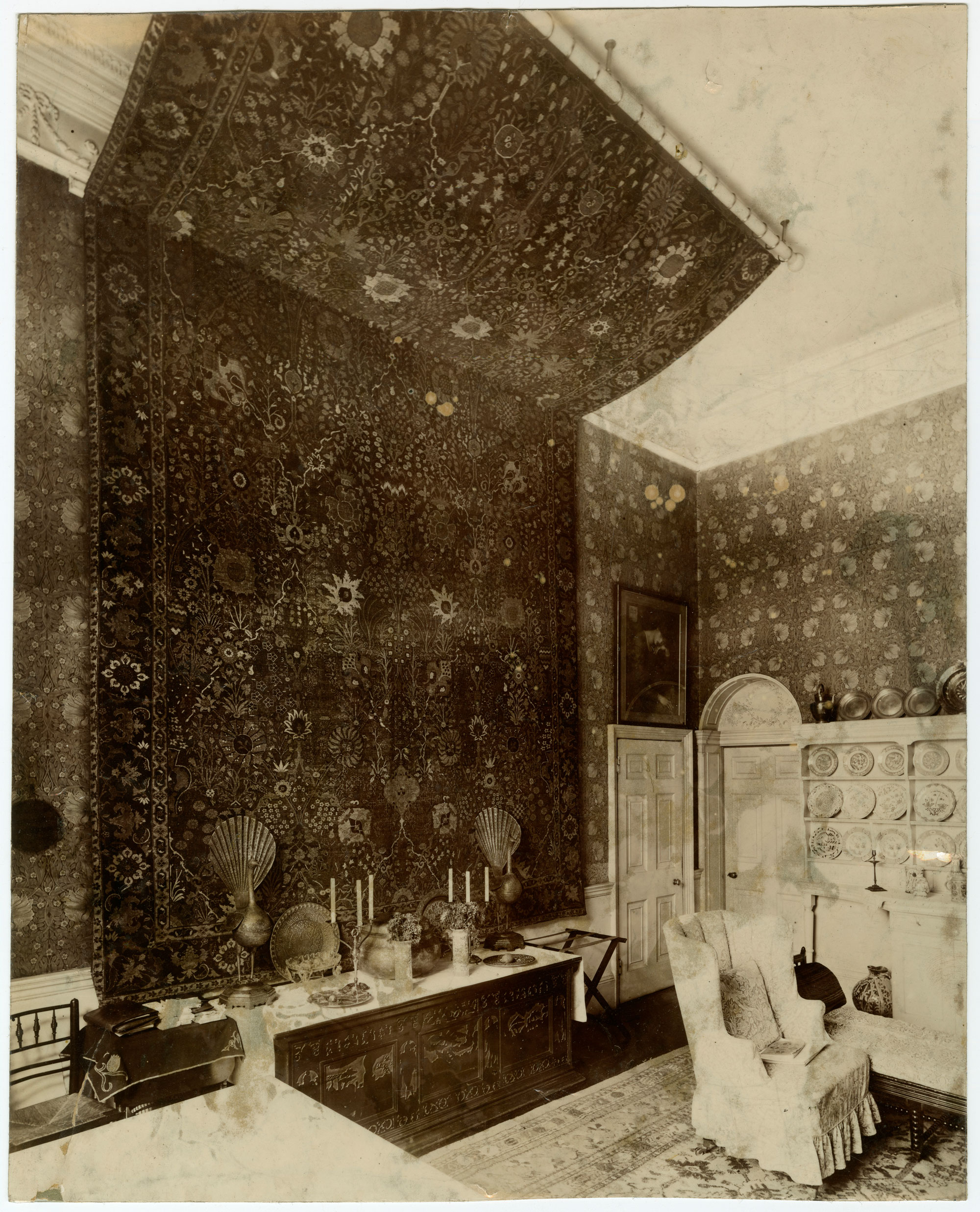

Morris’s own collections were extensive and varied, featuring objects such as carpets, textiles, metalwork, and ceramics from Iran, Turkey, and Syria. Some of his collections are well documented, preserved through photographs taken by his friend and neighbour, the printer Emery Walker, after his death. The interior photos of his dining room show a spectacular seventeenth-century Iranian ‘vase’ carpet hanging from a double-height wall and extending across half the ceiling [Fig. 1]. In front of it stands a pair of nineteenth-century Iranian brass incense burners in the shape of peacocks. These items are now preserved in museum collections—the V&A and Kelmscott Manor, respectively—and duly elevated to the status of Morris relics.

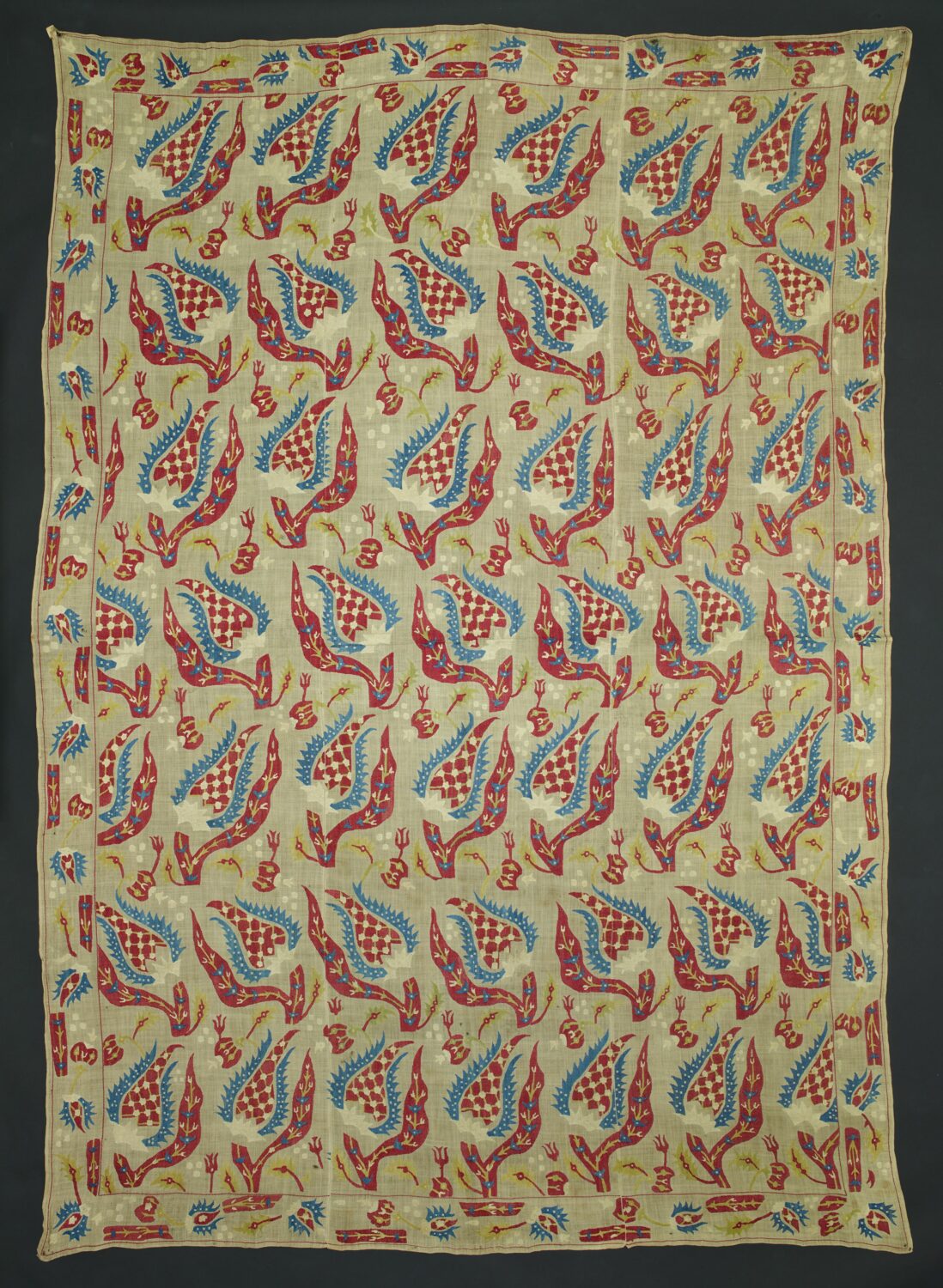

Other items, however, are not so well known, such as a collection of largely Turkish and Iranian textiles in Birmingham Museum Trust’s collection that were acquired after his younger daughter May Morris’s death in 1938. Largely overlooked by both curators of Islamic Art (not exceptional enough) and Victorian decorative arts (not Morris enough), the textiles are a mixture of woven silk fragments and household embroidery such as towels, pillowcases and quilt facings (yorgan yüzü) [Fig. 2]. Absent in Walker’s photos, these textiles were probably stored out of site, and taken out to be looked at or studied by Morris, or his wife Jane or May, who were both professional embroiderers and interested in historic technique.

The stand-out item in the collection is an Ottoman çatma, or silk velvet hanging, woven in Bursa, Turkey in the seventeenth century, which was used as the pall for Morris’s coffin [Fig. 3]. This work is not only an excellent example of textile art, but also reflects the deep personal significance it had for both Morris and his family.

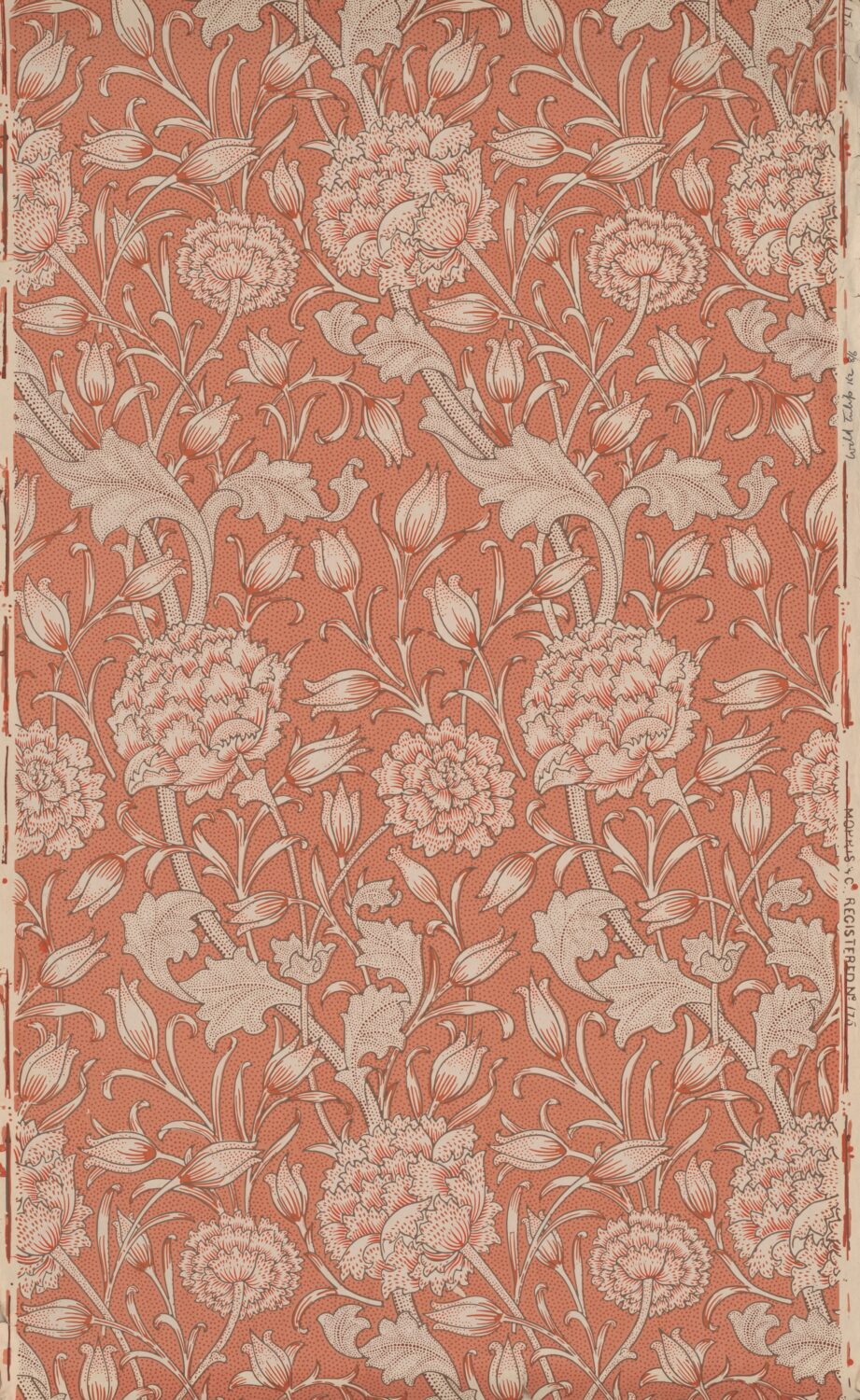

Morris’s collection practices and the subsequent distribution of these objects offer valuable insights into the interconnectedness of his work and the broader artistic and cultural exchanges between Britain and the Islamic world. Evident in Morris’s wallpapers and textiles are flower shapes and pattern-construction that can be visually compared to each other. His wallpaper Wild Tulip [Fig. 4] for instance, brings to mind the tulips and carnations found on the surface of Iznik dishes from Turkey, which Morris himself collected.

When making such comparisons it inevitably leads one to confront questions of cultural appropriation and artistic influence. Morris emphasised that true originality in art and design comes from deep engagement with tradition and craftsmanship rather than from striving for novelty: ‘The past is not dead, but living in us, and will be alive in the future which we are now helping to make.’ In other words, artists should draw inspiration from the past while infusing their work with their unique perspective and context.

Yet as a wealthy, Victorian businessman, Morris’s work also reflects the power dynamics of British imperialism. Whilst politically opposed to imperial tyranny, he profited from the greater trading opportunities that Britain’s Empire brought, as well as the import of raw materials. Morris is also not innocent of the problematic aspects of collecting practices in the 19th century, particularly the removal of sacred tiles from the Shia Shrine of Emamzadeh Yahya in Varamin, Iran [Fig. 5]. This discussion is crucial in understanding the broader implications of his collections and their interpretation in contemporary contexts.

The exploration of Morris’s collections provides a richer understanding of his artistic influences and the cultural exchanges between the Islamic world and Victorian Britain. It also invites further examination of the ethical implications of these collections and their display in modern institutions.

William Morris & Art from the Islamic World runs from 9 November 2024 to 9 March 2025 at William Morris Gallery, London.

Feature image: Isfandiyar Relaxes a While on his Way to Zabul, 1620, illustration from the Shahnameh (Book of Kings) by Ferdowsi, Gorgan, Iran (Safavid). © The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge