Interview: Dominic Chambers Explores the Parallels Between Painting and Literature

By Keshav AnandAmerican artist Dominic Chambers, hailing from St. Louis and currently based in New Haven, is best known for his vivid paintings that depict scenes of play and contemplation as a means to explore ideas of personal interiority. A writer himself, Chambers draws inspiration from diverse texts and movements, creating paintings dense with literary and historical references.

Opening today and on view until 9 November 2024, Lehmann Maupin in London hosts the artist’s first solo presentation in the UK. Expanding on themes of leisure probed in earlier bodies of work, the show, titled Meraki, spans two floors and includes vast paintings, experimental studies, and several new works on paper. Coinciding with the exhibition’s opening, Something Curated’s Keshav Anand spoke with Chambers.

Keshav Anand: How has literature, particularly the genre of magical realism, shaped your approach to painting?

Dominic Chambers: Literature has been a source of companionship for me. Many artists work extensive hours in solitude, and it’s been instrumental for me, both intellectually and personally, to develop a collection of shadow companions – writers and artists – who accompany me within my studio. Often, these companions are writers with whom I find a particular kinship. Artists also occupy that shadow space within my mind. In a way, I commune with them as I work through a specific idea or concern, both in regard to painting problems and whatever conceptual framing I’m working through.

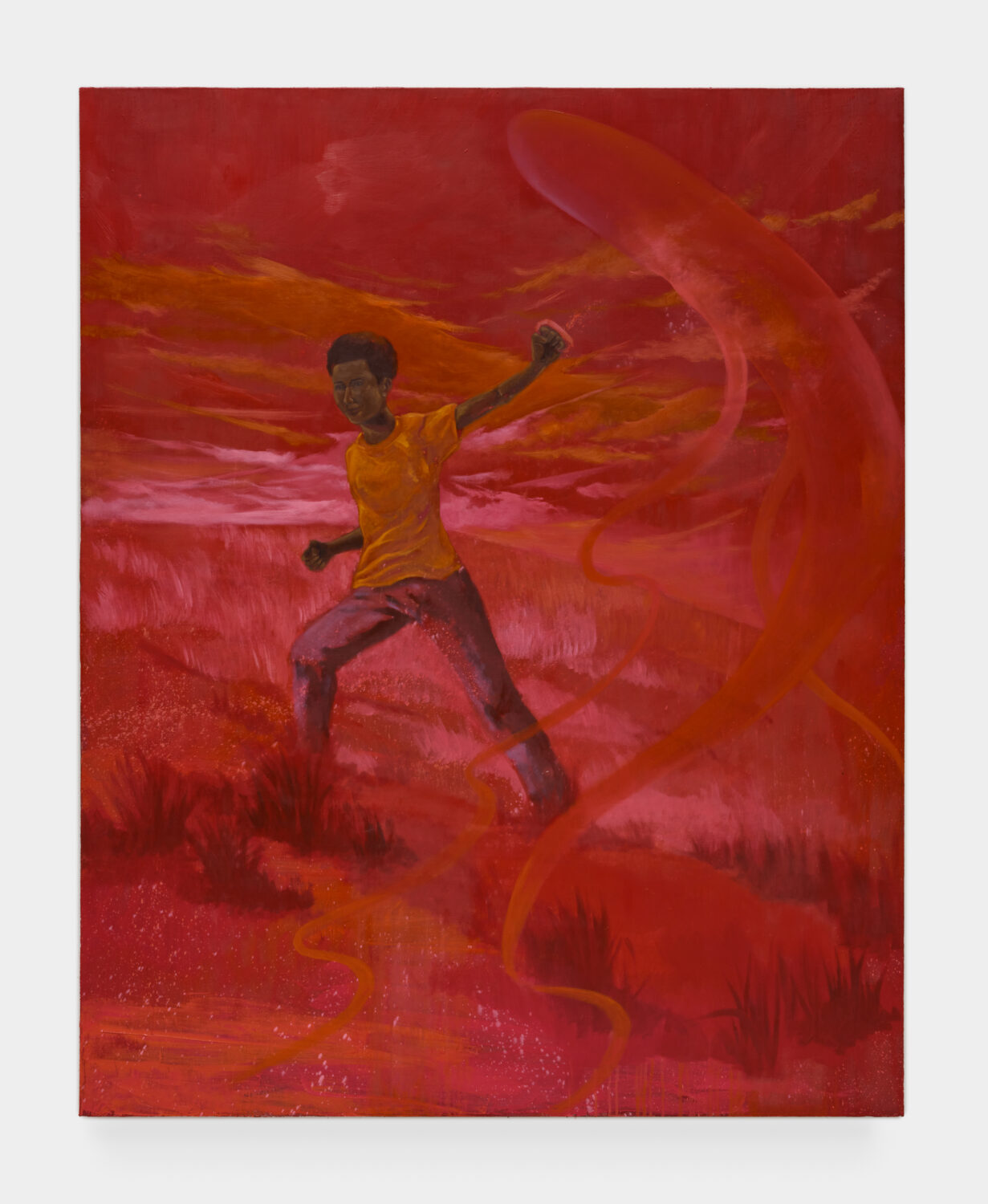

Magical realism, in particular, has been very useful as it has helped me to navigate several conceptual concerns within my studio. The literary genre is one I consider to be the written counterpart to surrealism, which often provokes a visual stimulus to me if that makes sense. Magical realism exists within the space of fantasy and faith, with the belief that our everyday experiences, especially for marginalised communities and people of colour, have a surreality to them. Unlike overt fantasy, which I associate with something like Harry Potter and Lord of the Rings, magical realism lives on the cusp of the natural order and the uncanny, yielding to the belief that surreal occurrences that defy reason quite literally happen and are inseparably experienced from the quotidian.

When I set out to make a painting, drawing, or any other work, I am conscientious not to separate myself from reason or stray too far from the realm of logic when thinking about how to give my ideas form while maintaining a sense of poetry and the surreal within the work. One of the things I am most excited about when making a painting is sharing an idea that visually announces an occurrence we can collectively experience.

KA: Delving further into texts that have influenced your work, what interests you in W.E.B. Du Bois’ idea of “the veil”?

DC: I became interested in W.E.B Du Bois’ idea of “the veil” because despite being first and foremost an examination of the social barriers that prohibit a fair assessment and understanding of the Black subject within a white-dominant society, the veil is also a clear example of how the language of surrealism is used to articulate the complexities of Black life. A surreal tongue has been used consistently among Black writers, as I noticed not only from Du Bois but also from James Baldwin, Octavia Butler, and Zora Neal Hurston, who applied language with a surreal tone to their examination of Black life in their writings. “The veil” is perhaps the most evident example, and I believe it to have a robust visual component to negotiate and render as paintings because its conception and function are a mode of abstraction.

KA: How have you approached selecting the works to include in your new presentation at Lehmann Maupin in London?

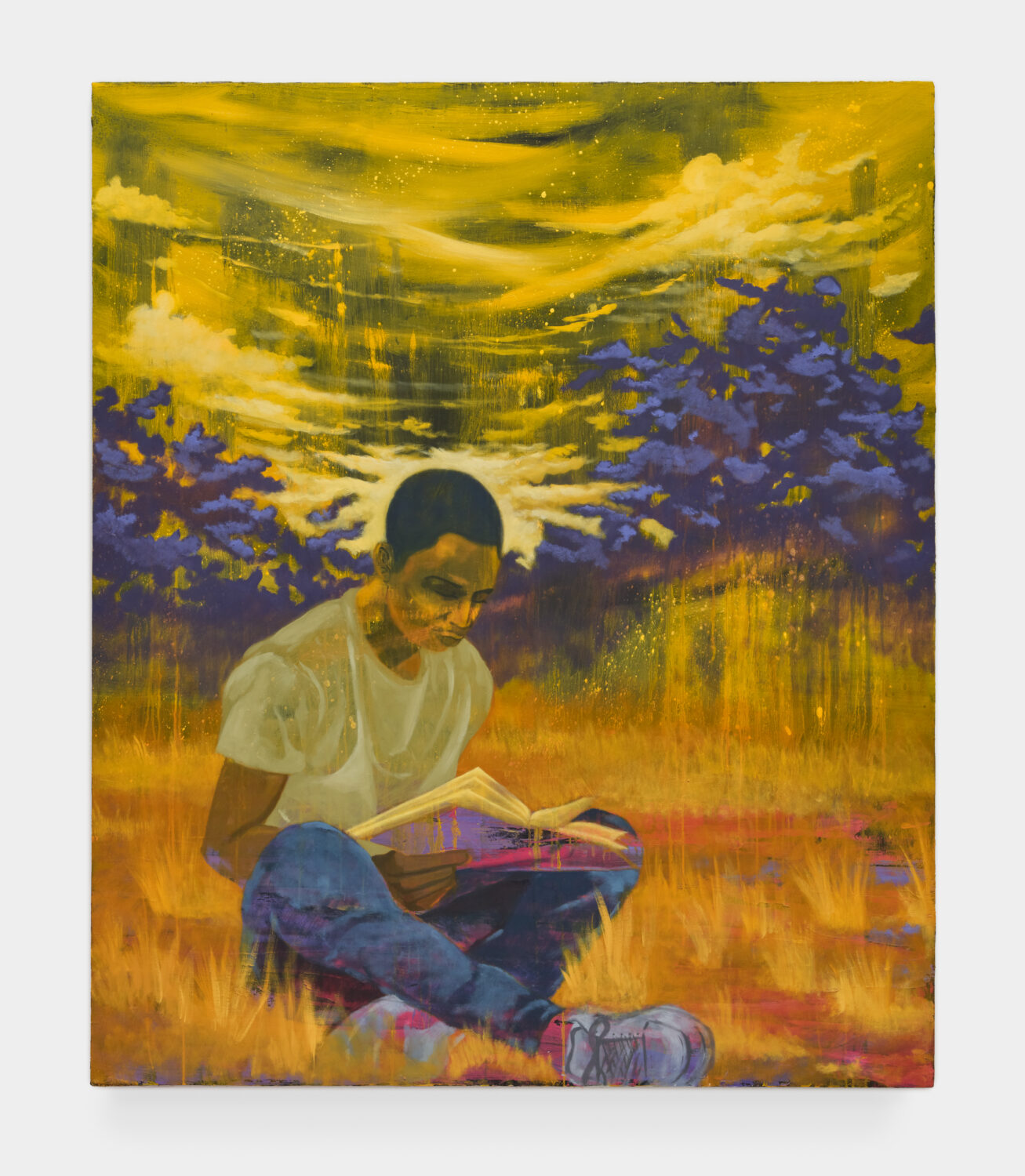

DC: I think in very conceptual terms when composing an exhibition. These days, I find myself contemplating interior realities – inner worlds – what resides there and its connection to the intellectual, spiritual, and wholeness of being. I’ve also been concerned with the lack of attention on Black interiority as a space of conversation when discussing Black life and experiences. The interior realities of my subjects have always been an anchoring principle in my paintings.

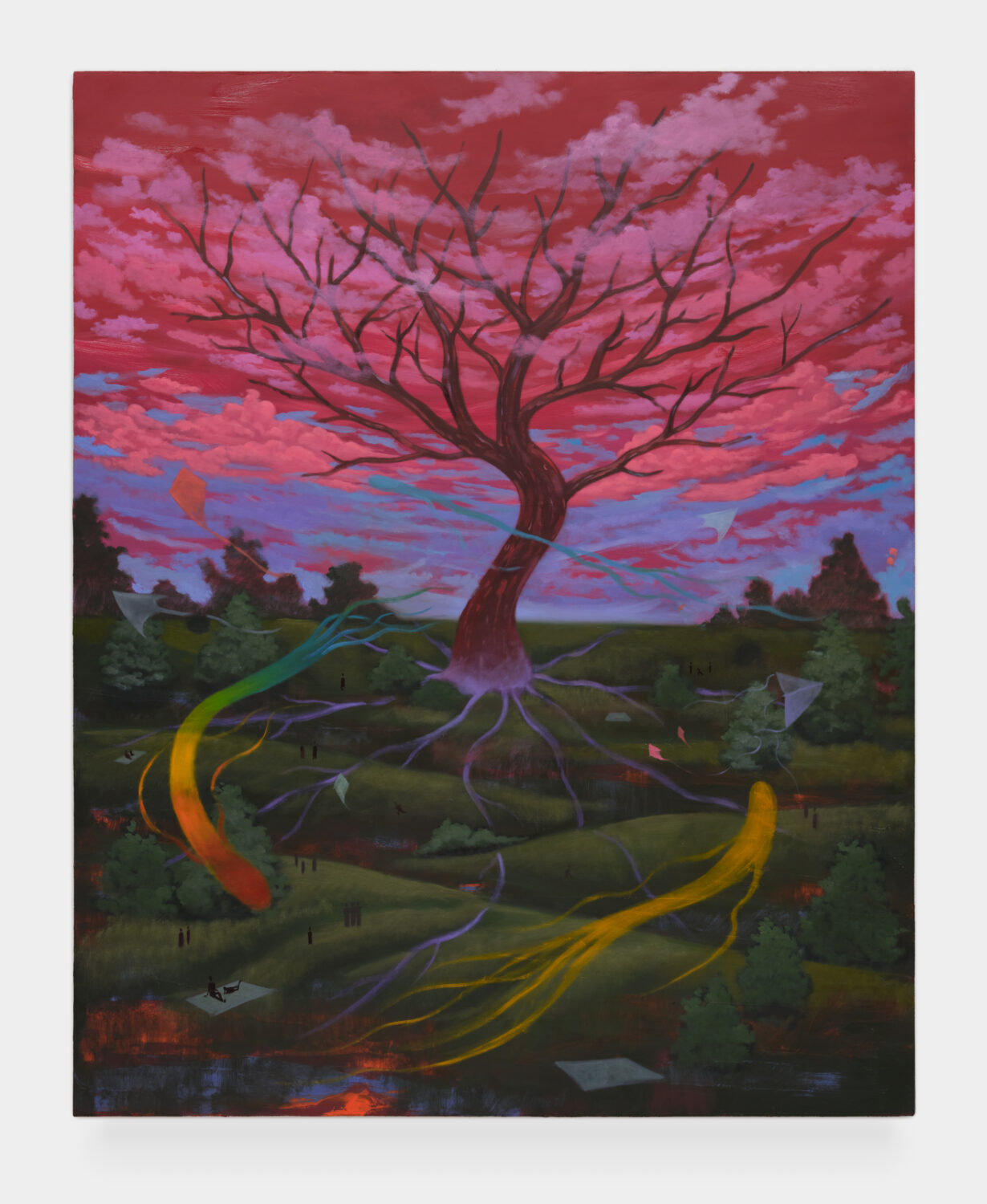

Painting the Black body in moments of rest allowed for a reconnection with and replenishing of its interiority through leisure or intellectual stimulus from a book. Moments that brought with them a sense of the surreal or the magical. My New York exhibition, Leave Room for the Wind, marked the moment I began to consider forms of kinetic leisure – things like kite flying – to explore interiority, rest, and the Black imagination further. As a result, massive colour-field scenes of kite flyers and paintings of stars and clouds took over.

For the exhibition in London, I have undertaken a somewhat different but closely related idea called Meraki, which means to pour one’s soul into the work that one does. I believe the soul and one’s interior landscape are closely related, if not the same. From here, I asked myself, “Well, how does one pour their soul into their work, and how is it made evident?” I don’t have a precise answer yet, and my ability to fully articulate a measure of the ideas to contain and neatly package the thought project is doubtful. Regardless, I am sure of this: Meraki, as I’ve grown to understand it, is undoubtedly another word for freedom.

Without giving too much away about specific works in the show, I’ll share that I consider this exhibition a sibling to Leave Room For the Wind and that each work represents an idea born from observations of the natural world and musings hatched from my imagination.

KA: Interesting. Could you expand on the role of leisure and recreation in your exploration of the Black experience?

DC: Leisure is the thing I associate the least with the Black experience. Growing up, I never heard anyone endeavour to rest, and leisure wasn’t a particular activity or state of being rewarded in my community. There seemed to be a need to work restlessly to keep one’s head above water. That was my initial observation of what I understood to be a reverence for working and equating the ability to work as a legitimising force.

I noticed a capitalistic social binding that felt securely wrapped around my community. Of course, I was also aware of the historical context under which Black people were brought to this country. Historically, Black people were conceived of and occupied the position in society as a subservient labour force. Not to mention existing as a literal form of monetary and social capital. Even if I considered the points in history in which Black people rebelled against their suppressors or protested for some form of right or another, a sense of hyperactivity is inescapable.

With my work, I wanted to dismantle that association, offer an alternative way of being, and exchange the idea of the labourer in favour of the unburdened saunterer. So, I made a lot of work depicting Black people resting, reading, daydreaming, etc. I also became interested in the possibilities made available when leisure is rendered as an essential ingredient to a fully realised life. From there, I began asking questions about what happens within those periods of rest and leisure. That’s when I started to imagine the role of magic and its ability to occur when the mind is allowed to rest, and in those quieter moments, the imagination takes over as a replenishing force.

One of the reasons I love magical realism so much is because, within its framing, an antagonist doesn’t need to be represented as an individual. I believe the antagonist can be considered more accurately as the insufficient social conditions plaguing marginalised communities. Considering the intersections of Black experiences, American history, art history, leisure, and magical realism was an exciting territory for me to explore.

KA: You’ve talked before about colour as a protagonist in your paintings. I’m curious to learn more about this.

DC: I think of colour as a protagonist because I am interested and invested in the language of colours and studying their interactions within a painting. While working through my images, much of the emphasis is placed on the interactions of each colour in relation to another to help illuminate a specific nature within the work. For me, colour isn’t simply a means to give form to an image or as an applicatory medium needed to constitute a “painting” per se, but to acknowledge colour as a changeling – a material that possesses the ability to evolve and elucidate more nuanced characteristics that aren’t immediately evident, but made all the more apparent through a meticulous mixing process with an emphasis on relationality. Considering this, I believe that if I wrote a book and personified colour as a protagonist with a function and mission, then colour would be a messenger – an envoy who delivers letters rich with variegation and robust language.

For the most part, I endeavour to provide a sense of magic through my use of colour because I consider the painting process a kind of séance or ritual undertaken by the painter. The colour in my work is also a device to illuminate a surreality within the environments I am building and the interactions between the subjects and the spaces they occupy.

Much of my work is related to colour-field painting, in particular, for this very reason. My appreciation of works by artists like Mark Rothko, Helen Frankenthaler, Sam Gilliam, and Richard Mayhew and colour theorists like Joseph Albers and Johannes Itten stems from their investments in studying colour as a changeling and providing the viewer an experience with colour that isn’t fixed but subject to fluctuations as a visual stimulus to our senses.

KA: Aside from home, where are your favourite places to eat in St. Louis?

DC: Hmm. I would have to say Blueberry Hill. It’s a popular and historical restaurant I recommend to anyone visiting the Delmar Loop. The Ferguson Brewhouse, in my opinion, has some of the best wings in the city, and its beer selection is terrific. Who Dat Southern Food Bar and Grill is another favourite of mine.

Feature image: Installation view, Dominic Chambers: Meraki, Lehmann Maupin, London, 2024. Courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Seoul, and London. Photo by Lucy Dawkins.