Inside the New York City Kitchen of The Baodega’s Charlene Luo

By Fifi Ding“Supper clubs are quite special because they’re very intimate and small and I’m able to physically be in the same space as the diners and explain every single dish. It’s a very different experience than in a restaurant…I’m basically giving a lecture while the meal’s taking place,” chef Charlene Luo says. “It’s educational and it’s also community building. In a restaurant you’re catching up with some friends, but at a supper club you’re meeting new people at the communal table. Hopefully, making New York City feel a bit smaller each time.”

This is how Luo describes the feeling of visiting The Baodega, a supper club she runs out of her Bed-Stuy apartment on Saturdays and Sundays. In a little over a year, it has gone quietly viral on the corner of Instagram occupied by NYC’s cool kid creatives. Luo serves Sichuanese home cooking — family-style — to groups of ten. Solo diners are encouraged to come, since these supper clubs are a way to meet others in a comfortable, casual setting.

TABLE

Charlene Luo: I feel like Sichuanese food is often flattened into a one-dimensional taste profile where it’s just flamingly spicy and numbing. While that is part of the flavor profile of Sichuanese food, it isn’t the whole universe. In terms of homestyle cooking – jiachangcai – it’s a very small component. One of the goals I have with The Baodega is to present homestyle Sichuanese food that gives the feeling of visiting your grandma’s house, your waipo cooking for you. Except it’s a waipo that cooks a 10-course meal.”

Opportunities to taste Luo’s food aren’t limited to her supper clubs. I met her doing a pop-up at CHA CHA, a public art festival celebrating the culture, aesthetics, and rituals of tea across different world cultures. Charlene’s table, located near interactive installations inspired by Pakistani, Japanese, and Chinese tea culture, was piled with ye’erba, sticky rice balls filled with ground pork, fermented yacai, and pork belly Luo cured herself on her apartment’s rooftop. Ahead of CHA CHA’s second weekend, Luo invited me into her home to see her preparation for the festival, which runs through February for Lunar New Year. Methodically, rhythmically, she portioned and filled ye’erba for the upcoming weekend while telling me about her journey and process.

PROCESS

Charlene started out cooking for her family on weekends as a teenager. This transitioned into cooking for friends in college, and while in grad school she had her first professional cooking job as a line cook, which she balanced with a corporate job in data science. She started The Baodega while working her corporate job, posting dinner parties to Instagram. A year and a half ago, she decided to take the leap to run The Baodega full-time. “It’s not all rainbows and butterflies,” she says. “You have to really, really love it to do it full-time. I think while we’re young, it’s a good time to take risks.”

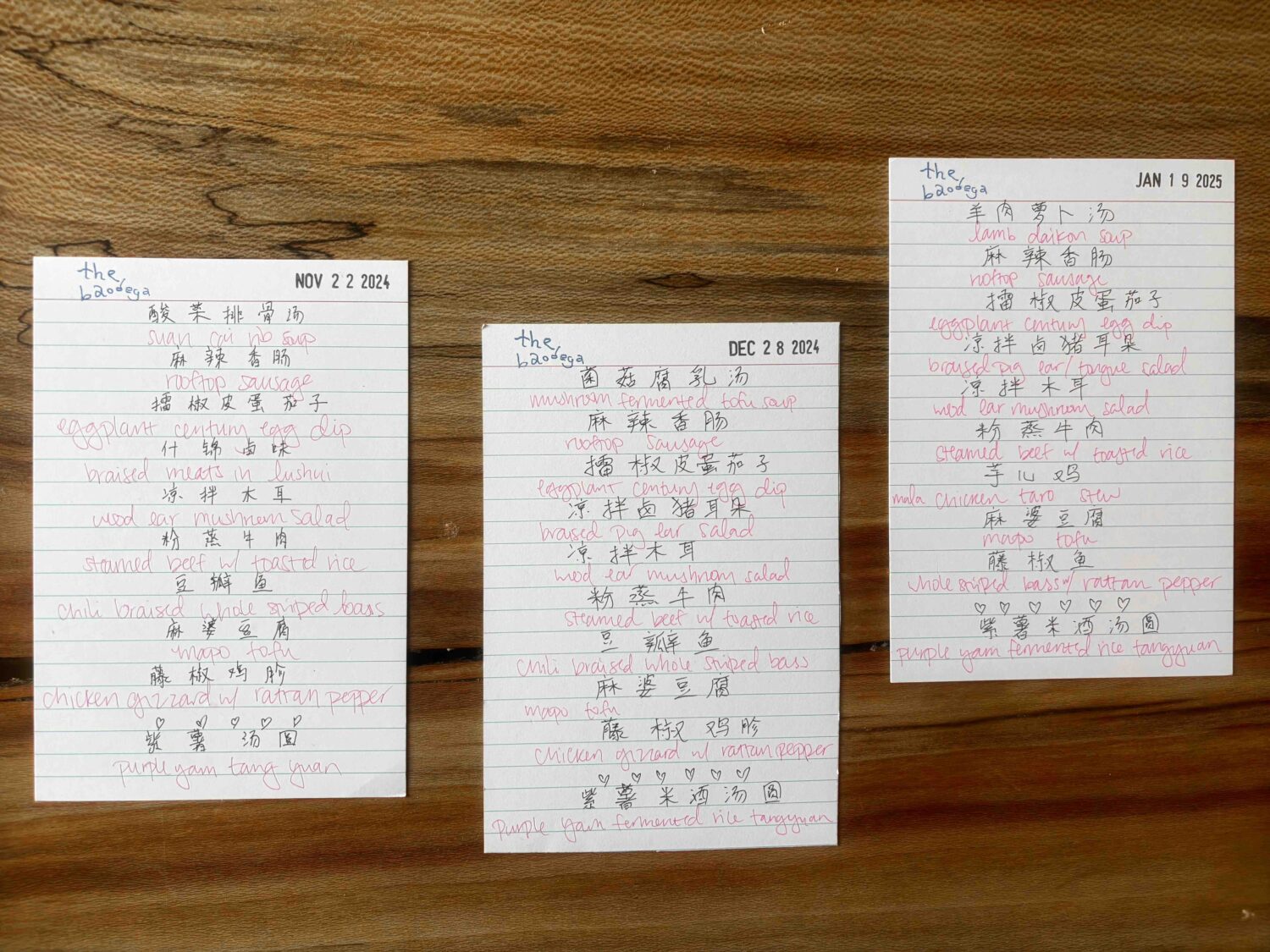

Menu planning is a production, an opportunity to showcase the best of the local markets while introducing diners to new things – a dimensional survey of Sichuan. “Of the ten dishes, maybe one or two changes every week,” she says. “I try to keep things seasonal. I want to cover a certain number of flavor profiles within Sichuanese food. I want to be able to use different types of protein that makes for a nice variety in the menu. That also applies to textures and temperatures.”

MENUS

CL: I reference a lot of old recipes. Most old recipes don’t have any measurements, and so it’s all by feel. It takes a lot of practice and knowing what you want it to taste like. A lot of my old cookbooks that I brought back from China are from the ‘60s and ‘70s. They don’t have any precise measurements. There aren’t a whole lot of cookbooks that have precise ingredient measurements that are the type of food I want to make.

CLEAVER

CL: In a commercial kitchen you’re making fewer things, but at huge quantities. In my supper clubs I’m making a ton of different types of things in much lower quantities. It comes with different challenges. I’m also working with equipment that isn’t necessarily commercial equipment, which comes with its own set of obstacles.

DOUGH BALLS

I asked Charlene about what it’s like when your home and work spaces are intertwined. Her definition of WFH is different from your average Zoom meeting attendee’s. “Very literally, my closet has become a freezer,” she says. Crammed under clothes hangers is a deep freezer packed to the gills with meat and broth. “My bedroom has become a pantry, and my rooftop garden is for my business use.” On the rooftop, she shows me the 90 pounds of sausages she spent the last two days curing, hanging on a trellis like meaty grapevines. It’s a testament to what one person can do with a vision and a will.

ROOFTOP-CURED SAUSAGE

Charlene Luo’s ye’erba will be on sale at CHA CHA Festival, running every weekend in February at WSA, 161 Water Street, New York City. Admission is free.

Fifi Ding is a writer based in NYC, where she’s part of the community team at the New York Times. Her work has appeared in Billboard, Time Out, and the Asahi Shimbun.

All photography by Fifi Ding. Photo editing by Frank Yin.