How Artists Have Adapted Chinese Paper-Cutting Over the Centuries

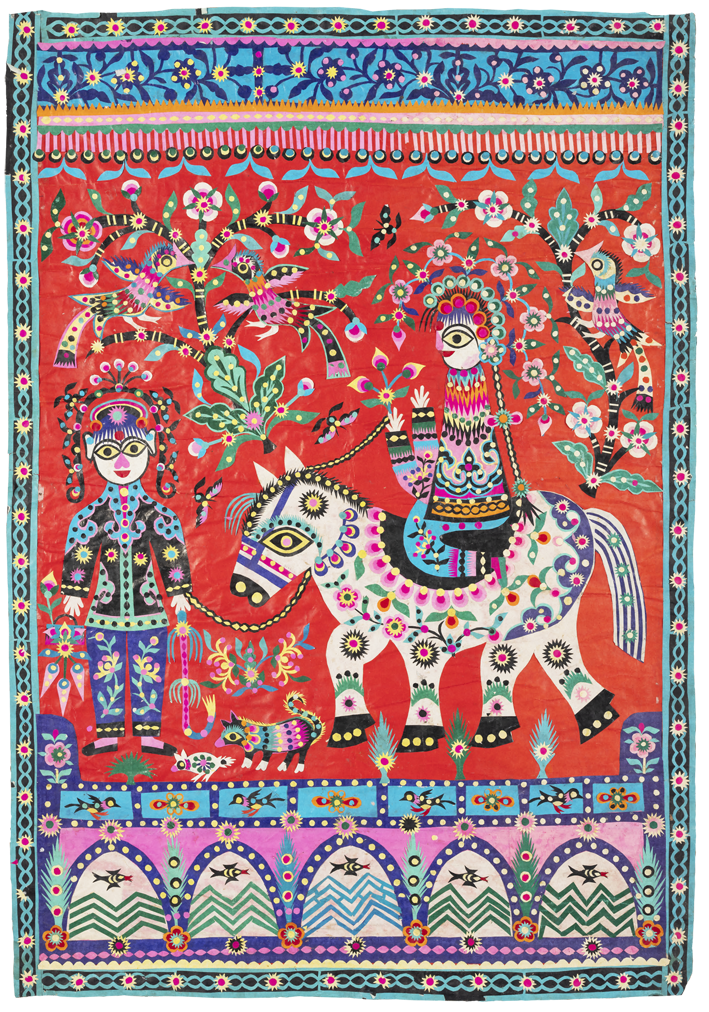

By Anna MossA rainbow coterie of animals, beasts, people and plants. A flock of bats, a resplendent phoenix, girls dancing and men playing music, chrysanthemum and lotus flowers – these are all familiar motifs of the Chinese Paper Cut, which in 2009, was inscribed on UNESCO’s list of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Painstakingly crafted with the simplest of household items – a knife or scissors – and pasted onto windows during festivals and celebrations, the history of the Chinese Paper Cut, known as Jianzhi, unfurls a rich artistic and ethnographic history.

FOLK ART: THE FADING AND FLOURISHING TRADITION

To understand the history of the paper-cut is to first understand its status as a folk art, and some of its accompanying complications. UNESCO’s cultural recognition of the paper in 2009 might be surprising, considering that the practice of paper-cutting is an ancient one. The oldest surviving paper cut, found in 1959 and excavated in Xinjiang, dates back to the 6th century. The earliest found examples of paper-cuts served often ritualistic and totemic purposes, to ward off tomb-raiders and bring luck and prosperity.

Over history, this craft evolved to serve decorative and domestic functions, whilst retaining their original spiritual sentiments. Following the widespread manufacturing of paper during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE- 220BCE), the potential for paper cutting blossomed, so much so that it would begin to be regarded as a form of ethnography in the 20th century. There are idiosyncrasies not just amongst artisans, but regional differences between the Yellow River and Yangtze basins. The folk tradition of paper cut has roots in the Northern region, where its practices flourished, particularly in the provinces of Shaanxi and Shandong, before it then spread to the Southern regions of Guangdong and Fujian provinces.

Shaanxi was the birthplace of Ku Shulan, who is regarded as one of the ‘masters’ of paper-cutting or the ‘Goddess of the Paper Cut’. Her creations were highly distinctive, known for their vibrant, graphic quality: larger-than-life eyes and rhythmic patterns. As with many highly skilled paper cutters, her intricate designs were cut freehand, without following a drawing. Creating multichromatic layers, Ku Shulan’s distinctive collage technique came to exemplify the bright visual language of folk paper-cutting. But behind the joyous spirit of these works, her life was marked by poverty and hardship. Born in 1920 to a peasant family, Ku Shulan learned paper-cutting in preparation for marriage, as was tradition. She endured domestic violence at the hands of her husband, and lost several children due to starvation.

Amidst this suffering, Ku Shulan sought refuge in her craft. Her immense, decades-long artistic output tells a remarkable narrative; one of folk songs, rural life, joy and sadness. Her skills were known only to her local community, until in the 1980s, there was a renewed research interest in folk art. In 1988, Ku Shulan’s paper-cuts were shown at the Xunyi Folk Papercutting Exhibition, a landmark exhibition in partnership with the National Museum of China. Only in the twilight of her life did Ku Shulan gain recognition as a true artist and pioneer. In an incredible, near mythical story, at the age of 65, Ku Shulan had a near-fatal fall into a ravine, and was unconscious for nearly forty days. Awakening from her coma, she proclaimed that she had been blessed by a ‘Goddess of Paper-Cutting’, a figure that after this experience, would then feature in every single work.

Her story stands as one representation of the lives of many other female artisans, who though not as famous, possessed extraordinary artistic sensibilities, without being able to read or write. Paper cutting as a practice was intricately linked to the lives of peasant women, as the patterns were ubiquitous in daily life and often used for embroidery. Though bound up within domestic life, the art of makers like Ku Shulan envisioned a world far beyond the domestic. Folk art scholar Lu Shengzhong noted that Ku Shulan’s creations ‘do not simulate nature’s image, but in conceptual modelling, profoundly expressing the sublime and a longing of a spiritual self.’

The ‘discovery’ of Ku Shulan and many other artisans, such as Cao Xiuying and Gao Fenglian, all of whom found fame in old age, gives as an insight into the art historical and political factors underpinning folk art. It was only due to a dedicated department of folk art, set up in 1984 by the then head of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, that Chinese folk art became a legitimised field of study. Further still, the specificity of the art and tradition require different research methodologies. Wang Xiao, curator of the Shanxi Province museum states: ‘distinguishing itself from elite art, folk art thrives and fades away like wildflowers and weeds, with few predecessors documenting it.’ Folk art demands first-hand experience, rather than the consulting of preexisting accounts: only with some fourteen field trips to the Yellow Basin area in 1984 could the work of Ku Shulan and her contemporaries be found.

PAPER CUT: A LANGUAGE OF SYMBOLS

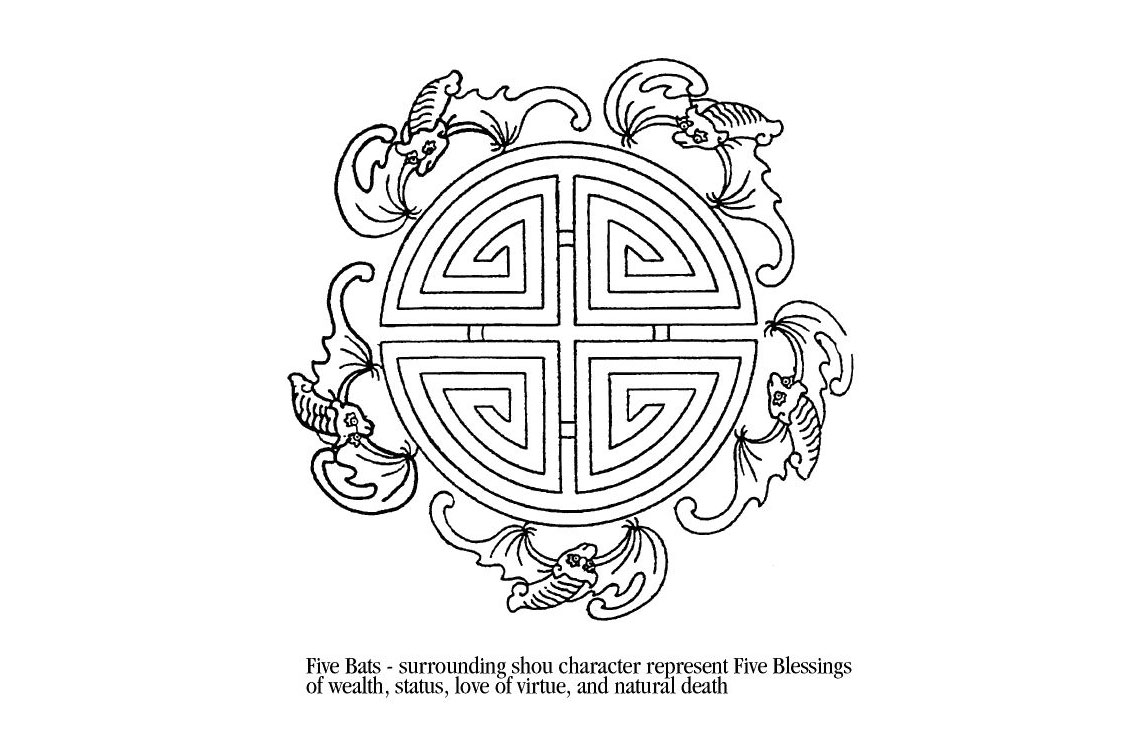

Though the stylisations and methods of paper cutting across China vary widely, there are popular symbols found in the craft that tell us about Chinese culture nationally. The bat, a common motif seen during New Year’s, signifies good luck, due to the Chinese words for ‘bat’ (蝙蝠, biānfú) and ‘blessing’ (福, fú) sounding the same as homophones. These small, delicate creations – no larger than the palm of one’s hand – are instilled with a strong sense of belief and hope. Another beloved symbol is a chrysanthemum, long lauded for its thought to bring longevity. One book from the Han Dynasty, Fengsu tongyi 風俗通義 credits the villager’s life expectancy of 130 to their water supply flowing over chrysanthemums that grew on the village’s mountainsides.

Peonies, known in China as the ‘Queen of Flowers’, is also the subject of plentiful myths of resilience. The female Emperor, Wu Zetian 武則天, ordered flowers to bloom immediately: all flowers except the peonies blossomed, leading her to vengefully burn the entire peony population. The following spring, the peonies arose from the ashes, resilient. In Eastern tradition, peonies are a symbol to the people of strength. The symbols found in paper-cuts are not simply embellishments: they are powerful conduits that impart Chinese cultural heritage, including real and mythological accounts. The linkage of Chinese language and symbolism means paper-cutting is accessible to people of all ages and levels of education – it is a communal art form, colourful both in style and narrative.

BLOOMING AGAIN: CONTEMPORARY PAPER CUTTING

Paper cutting is still practiced today in China’s rural communities, and alongside it, the scholarship on the folk craft continues to develop. Cheng Zheng, the researcher who founded the field for research into folk art, has had a life-long devotion to its study.

Away from the folkloric styles of the twentieth century, contemporary artists carry on the legacy of Chinese paper cutting. An exhibition at London’s Somerset House, Blooming on Paper, curated by Yanyi Chen, Tengzi Li, Ran Yan and Yi Zhou, and organised in partnership with the Shaanxi Province Museum, brings together the works of Ku Shulan with contemporary artists. Featuring a line-up of nine female artists, the exhibition stands as a testament to the paper cut as tied to women’s lived experience, even as the forms of paper-cutting evolve. Nayeon Han’s poignant work, Release to Embrace, tells the very personal story of her miscarriage through sculptural layering and collaging. Han’s visual language feels architectural, whilst still retaining the beautifying and emotive power of the traditional paper cut. Lihong Bai’s work explores themes of self and desire, creating repetitive, circular forms with ink on paper. Drawing upon the principles of Zen philosophy, her art disrupts and breaks free from traditional artistic training.

Artists Annie Edwards and Victoria Kosasie directly honour Ku Shulan’s life in their moving performance, Paper Score. Standing opposite one another, the pair carve silhouettes from paper screens using craft knives. Audiences hear nothing except the slashing sounds of paper, delicate yet assured, as forms of their paper counterparts emerge from each artists’ cutting. These large paper figures are reminiscent of Ku Shulan’s ‘Goddess of the Paper Cut’. But what is truly striking is the synchronisation of the pair; their non-verbal signals to each other as they click their knives. This simple sound seems to represent the very practice of paper cutting: an intimate ritual, an experience at once deeply personal and shared.

Blooming on Paper runs until 19 March 2025 at the Inigo Rooms, Somerset House.

Bibliography

Britton Newell, Laurie. Out of the Ordinary: Spectacular Craft (London: V&A Publications and the Crafts Council, 2007)

Hawley, W. M. Chinese Folk Designs: A Collection of 300 Cut-Paper Designs Used for Embroidery Together with 160 Chinese Art Symbols and Their Meanings. (New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1949)

Mullen, Nicole. Chinese Folk Art, Festivals, and Symbolism in Everyday Life (Berkley: Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology, 2005)

Xiao, Wang. Go to the Folk: The Story of a Suitcase (Shaanxi: Shaanxi Province Art Museum, 2024)

Zhang, Daoyi. The Art of Chinese Papercuts. (Beijing: Foreign Language Press, 1989)

Zheng, Cheng. ‘Will the Ocean Dry up?’, in Art Magazine, Issue 5. 1984

Feature image: Release to Embrace by Nayeon Han. Part of Blooming on Paper