Stella Paul: Celebrating Black Architecture

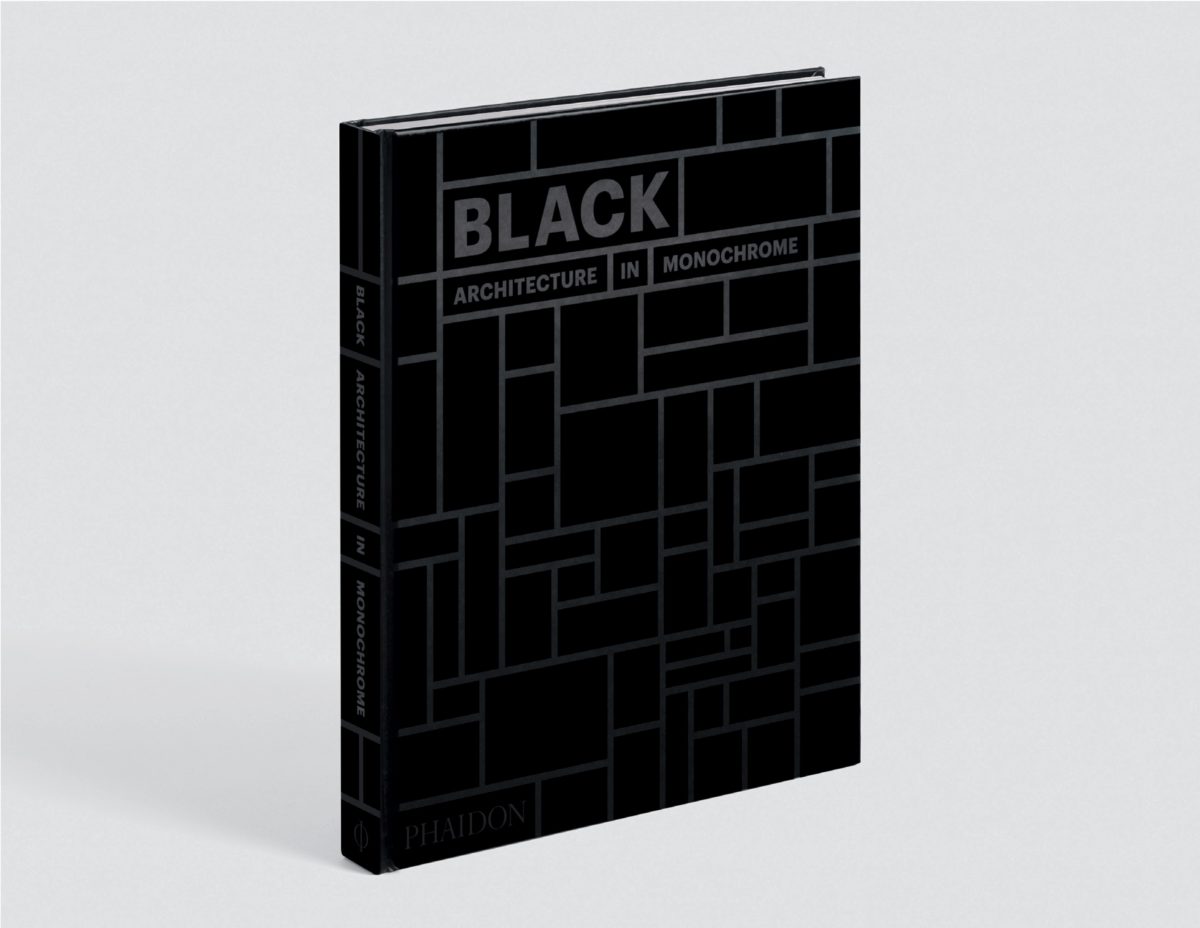

By Something CuratedPhaidon’s Black: Architecture in Monochrome is a fascinating survey of the intensity, strength and mystique of the colour black in the constructed world. Holding a strong cultural and historical significance – whether signalling transgression or devotion, penury or luxury, introspection or extroversion – black is at the centre of both personal and social experience, making this thought provoking compendium exciting and relevant. The tome features over 150 diverse structures covering 1000 years of architecture, comprising significant historical landmarks that have shaped the record of building in black, and showcases works by some of the most notable architects of the twentieth century including Philip Johnson, Eero Saarinen and Mies van der Rohe, alongside celebrated contemporary architects such as David Adjaye, Jean Nouvel, Peter Marino and Farshid Moussavi. Something Curated spoke with author and colour specialist Stella Paul, who wrote the book’s introduction, to learn more.

Something Curated: Where does your interest in black architecture stem from and what motivated you to contribute to the book?

Stella Paul: I have been immersed in issues about colour forever – it seems. I’m fascinated with what it is, how it is used to shape the world we live in, and its immense power to control aesthetics and meaning. Ideas about colour have led people and societies to passions—and predicaments—that would surprise you. Keeping colour at the forefront has taught me to look and think about things differently. Whether I’m focusing on art objects or the built environment, if I consider it through the lens of colour, I invariably come to a deeper understanding. The Phaidon editors know all about my keen interest in colour, because I recently published a book with the press, called Chromaphilia: The Story of Colour in Art (2017). I devoted a whole chapter in Chromaphilia to black, which has inspired some of the most fantastic art ever created. Black’s depths are limitless, and fascinating to think about. When the Phaidon editors invited me to contribute to Black: Architecture in Monochrome, I was delighted at the opportunity to give black even more thought.

SC: What in your opinion is one of the most interesting buildings featured in the anthology and why?

SP: I can’t help but choose two rather than just one. Both are compelling visual manifestations of belief and worldview, expressed perfectly through black, which takes centre-stage. One building helps us understand a deep history of the colour, and the other brings us into the contemporary world. The House of the Seven Gables (1668) in Salem, Massachusetts, with its sombre black wood cladding, is a striking embodiment of puritan ideals and strictures. It evokes historical codes of behaviour that permeated society at this time on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean, where other colours were equated by some with ostentation and frivolity—or worse. Black, on the other hand, reflected the austerity and gravity of the pious. We know how marvellously protean color-codes are, changing with the context of time and geography. But here, with this seventeenth-century structure, the colour code is explicit and direct: black’s sombre restraint is a recognisable cultural metaphor.

The Kärsämäki Shingle Church (2004) in Finland embodies a metaphor for spiritual enlightenment, and a path to get there. This building plays on a distinction between the outside and the inside, which goes from black to light—using monochrome to pass from one state of being toward another. Black is the foundation underpinning the whole experience. The church’s unremittingly black exterior is comprised of 50,000 hand-split shingles, all dipped in tar. The material itself (tar) is both colour and function, since it acts as a sealant against weather. The architects have used vernacular techniques in this contemporary building, carrying into today’s world the long-standing traditions of the region. I’m always fascinated by how we can build on the conventions of the past to create new expression. This building does that, plus it uses the binary colour distinctions to tell a story. And it reminds us, as readers of the book, that buildings are three-dimensional structures that we move through. This building’s central metaphor (a path from dark to light) is based on moving from outside to inside.

SC: Could you expand on the idea of black historically being used to assert privacy?

SP: Keep in mind that black is capable of playing a lead role, whatever the drama. So there is definitely such a thing as showy or flamboyant black, too. But inky, matte black absorbs light, and the absence of light can make it inconspicuous, metaphorically keeping it out of the spotlight. The capacity to recede from viewpoint helps the colour become a tool to create a zone of privacy. Add to that its long-standing identification with seriousness and austerity, and you can conjure up an easily understood statement to an onlooker: “this is private.” Documentation about dress codes and technologies for dyeing textiles deep shades of black from the fourteenth century on in Europe help us understand, pretty directly, the value of colour in sending messages.

The built environment, too, uses colour to communicate. Those messages evolve and layer depending on time and place. In one historical moment (the Protestant Reformation, for example) black signalled devotion and prudent restraint. In another time, black’s restraint leads straight to privacy. Modern and contemporary buildings with austere black surfaces, with ingenious technologies to batten down, shield, and veil their insides—point to a predilection for privacy. So that’s one through-line in the story of black. Yet a disclaimer is important here: as true as this is, it is nevertheless not universal. Black’s amazing nimbleness—to tell so many different stories—is one of its great attributes.

Feature image: Roads and Waterworks Support Center, Harlingen, The Netherlands, 1998, Neutelings Riedijk Architects. (Photo: Neutelings Riedijk Architecten/Christian Richters)

Interview by Keshav Anand