Exploring The 1970’s Extreme Aestheticisation Of The Bathroom

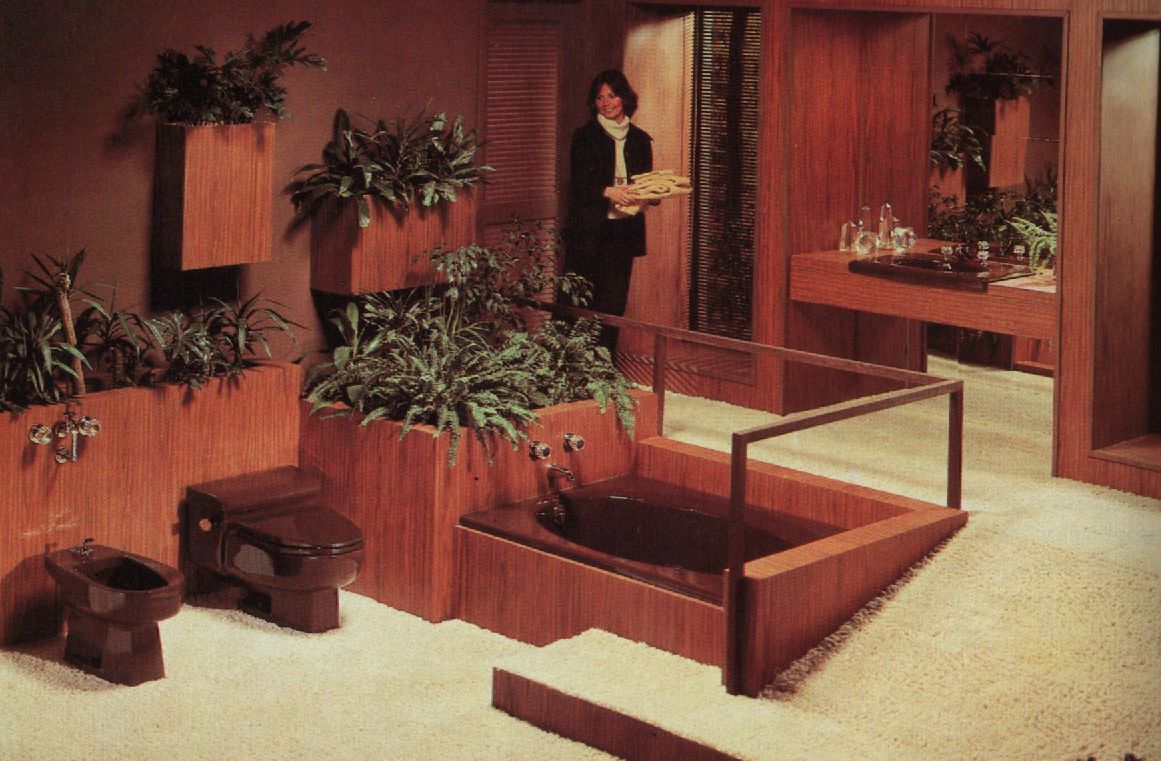

By Something CuratedThe 1970s heralded an era of joyously bold and seemingly incongruous design choices. An age best known for its earth-tone patterns, influenced by the burgeoning environmental movement, unrestrainedly decadent entertaining areas of marble, brass and fur, and busy textiles and wallpapers, the 70s marked the heyday of the concept bathroom. For those who could afford to, domestic bathing spaces became temples of leisure and play, with uncompromising attention paid to style, as well as comfort.

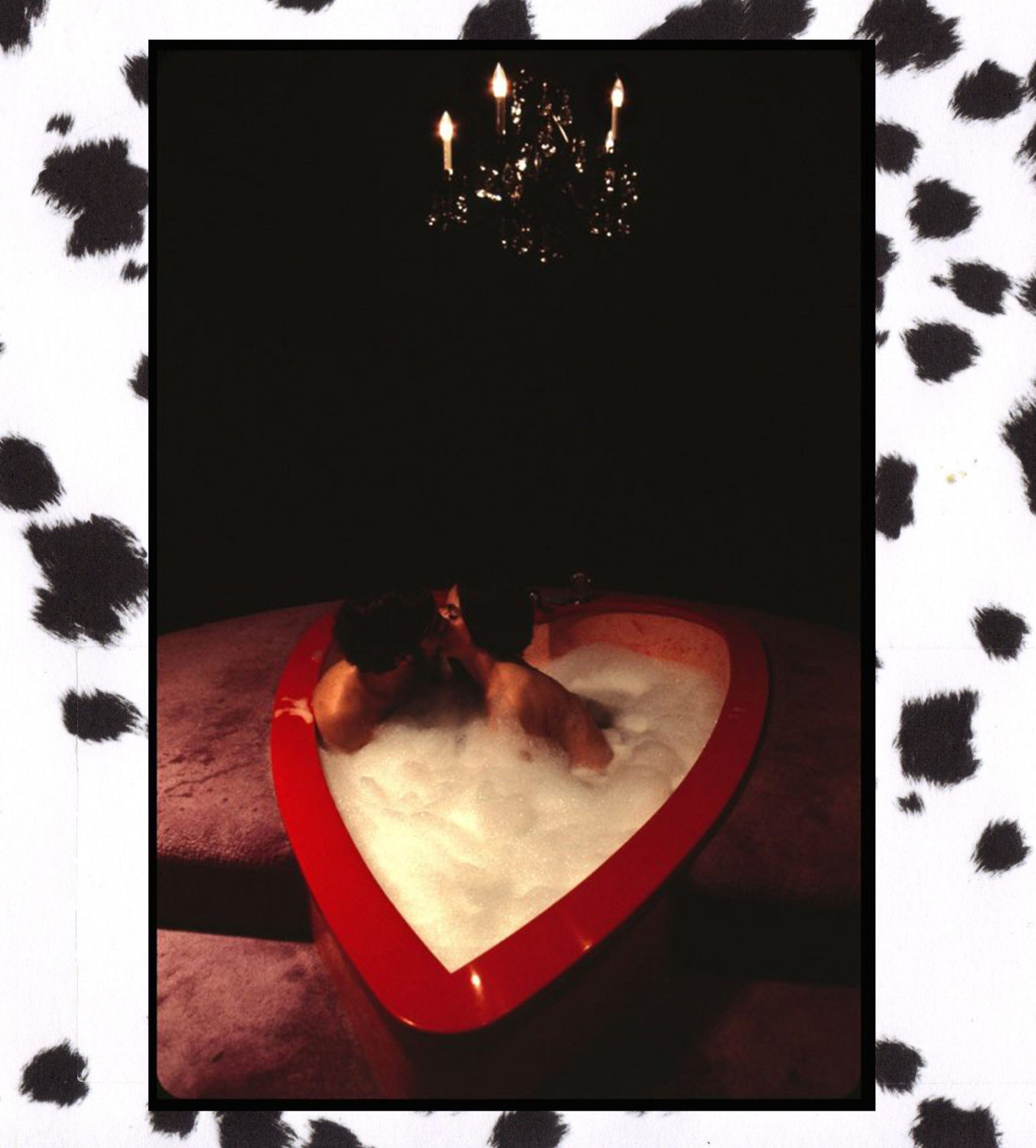

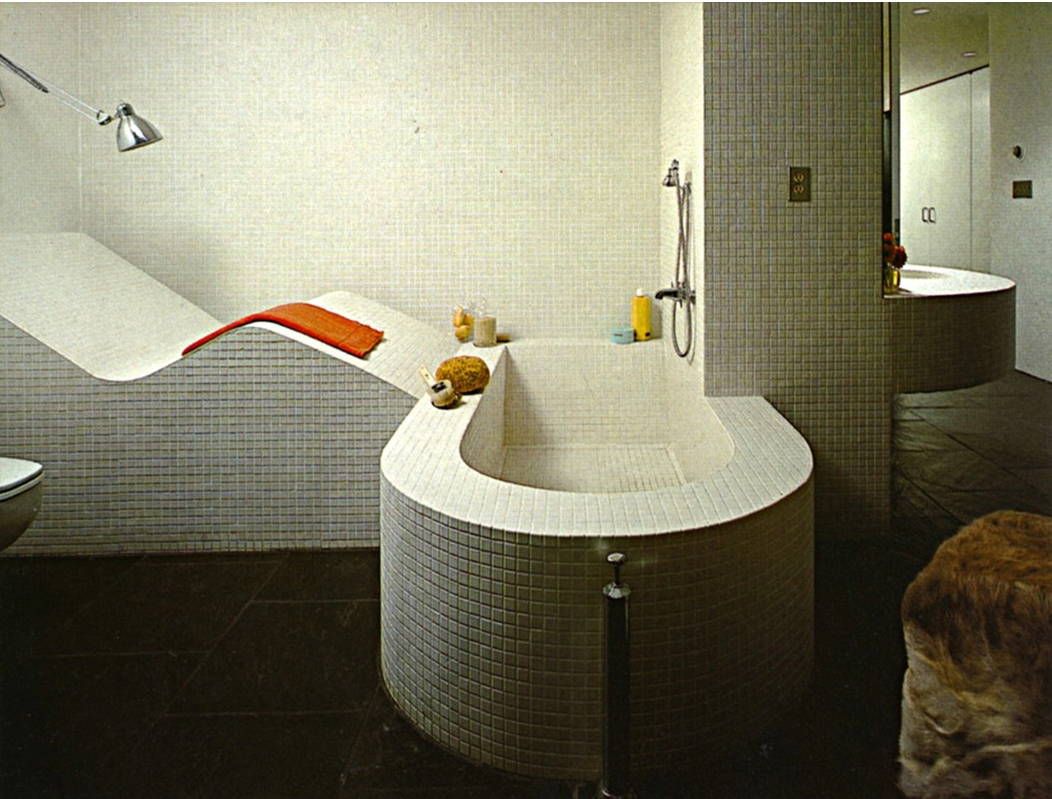

Design critics David Netto and Tom Delavan write, “In contrast to the pared-down discipline of mid-century style, the 70s were sensual and decadent. People were unafraid to take risks. The furniture was made for hanging out, lounging or sex — activities infinitely more tempting than what was going on in the places where postwar design made its mark: schools, offices and hospitals. Imagine trying to make out on a Barcelona Chair.” From the unreservedly kitschy, heart-shaped tubs of the Honeymoon Hotel in the Poconos Mountains of Pennsylvania, build in 1971, to George Nakashima’s 1977 mosaicked masterpiece, the Sanso Villa bathroom, the 70s birthed a number of the most ambitious and irreverent bathroom interiors to date.

Delving further into the history of the bathroom, in medieval England, most people washed in public baths, taking after traditions of ancient Rome, Byzantium and North Africa. Shared by men and women, in 1546 these so called ‘stews’ were shuttered by Henry VIII, owing to the lewd misconduct they fostered. It was in the 1850s when British artisans conceived the now ubiquitous ceramic glazed tub. Due to the tubs’ fragility and considerable weight, they were difficult to export abroad, but the idea found a market across Britain, and by the 1890s, solid porcelain tubs were made by leading manufacturers including Trenton Potteries.

Even so, some 30 years later, during the 1920s in London, a private bathroom was still deemed a luxury. When the Bermondsey Public Baths opened in 1927, only one out of every 500 houses had a bathroom. What they lacked at home, including a lavatory of their own, local residents found in a grand municipal building comprising multiple swimming pools and 126 private baths in cubicles along with steam rooms and saunas. For centuries, in many parts of the world, this is how people without access to personal bathrooms kept themselves clean.

Prior to household plumbing, bathtubs, like chamber pots and washbowls, were portable accessories, often cumbersome but relatively light containers that bathers pulled out of storage for temporary use. The typical mid-19th-century bathtub in the US was a product of the tinsmith’s craft, a shell of sheet copper or zinc. In more affluent homes equipped with early water-heating systems, a large bathtub might be site-made, fashioned from sheet lead and housed within a wooden shell.

As running water became more common in the latter 19th century, bathtubs became more prevalent and less portable. By the mid 20th century, once the bathroom reached a plateau as an effective and sanitary cleansing room, it began to be viewed as a playground for design, and colour came into the space. Pigmenting the largely generic fixtures, at first in light pastels, then in deeper hues, like striking reds and jade greens, brought colour to the bathroom in unexpected ways.

Colour became a useful marketing tool for manufacturers, differentiating one product line from another, as well as giving homeowners reason to buy all fixtures from the same source. As fashions changed, by the 60’s, once again, lavatories began resembling domestic furniture, rendered in woods and metals, sometimes covered in plastics and even textiles. Emulating chairs and beds, for example, toilets and bathtubs became finished in a breadth of materials, spanning marble, leather, poured resin, and even, rather ostentatiously, precious metals, taking on sculptural forms, and giving way to the unfettered creativity of the 70s.

Bibliography:

David Netto & Tom Delavan, ‘Loving the Unlovable Decade’, The New York Times, 2015

Jonathan Glancey, ‘How the design of the modern bathroom evolved’, BBC, 2017

Julienne Hanson, Decoding Homes and Houses, Cambridge University Press, 1998

Terence Conran, The House Book, Crown Publishers Inc., 1976

‘The History of the Bathtub’, Old House Journal, 2019

All images via Pinterest