Interview: Painter Jessie Makinson On Temper Tantrums & Setting The Scene

By Something CuratedLondon born and based artist Jessie Makinson’s mesmeric paintings are funhouse mirrors of historical and literary references, reflecting eclectic allusions askew. Discover nods to 18th century brothel scenes and Georgian parlour games, ancient folklore and contemporary eco sci-fi. The titles of her works come from similarly diverse and diffuse sources – overheard snippets of conversation, quotes from cooking shows and 60s novels, anywhere really, and often taken out of context. Figures twist, bend, sit and splay at uncanny angles across unstable grounds, their cool stares suffused with mischievous ambiguity, simmering schemes and latent desire. Following the completion of The Drawing Year Postgraduate Programme at London’s Royal Drawing School in 2013, Makinson has had solo exhibitions in New York, Zürich, and Mexico City, as well as numerous group shows across the world. To learn more about the artist’s work, her recently concluded exhibition of new paintings at Los Angeles gallery François Ghebaly, and what she has planned next, Something Curated spoke with Makinson.

Something Curated: Can you give us some insight into your background; when did you first become interested in painting?

Jessie Makinson: I grew up in Camberwell in London. I’ve always been interested in making things, drawing and painting; I don’t remember otherwise. I studied at Edinburgh College of Art, The Royal Drawing School and Turps Banana.

SC: How do you think about storytelling through your fascinating works?

JM: I am interested in the ability of painting to hold many narratives, to act as a vessel that allows space for untold stories, contradictions and questions. I am always trying to generate ways of working that allow me to access stories and my subconscious without looking directly at it – to surprise myself and trust my ability to set the scene without telling the story. I consider storytelling in terms of the gathering, collecting, and organising of hints, scraps, and whispers. It has a lot to do with a hunch that if I bring certain things together, they will activate each other. I don’t think too much about the story that I’ve made or how it will behave, as I find the contradictions, misunderstandings and awkward groupings that happen more interesting.

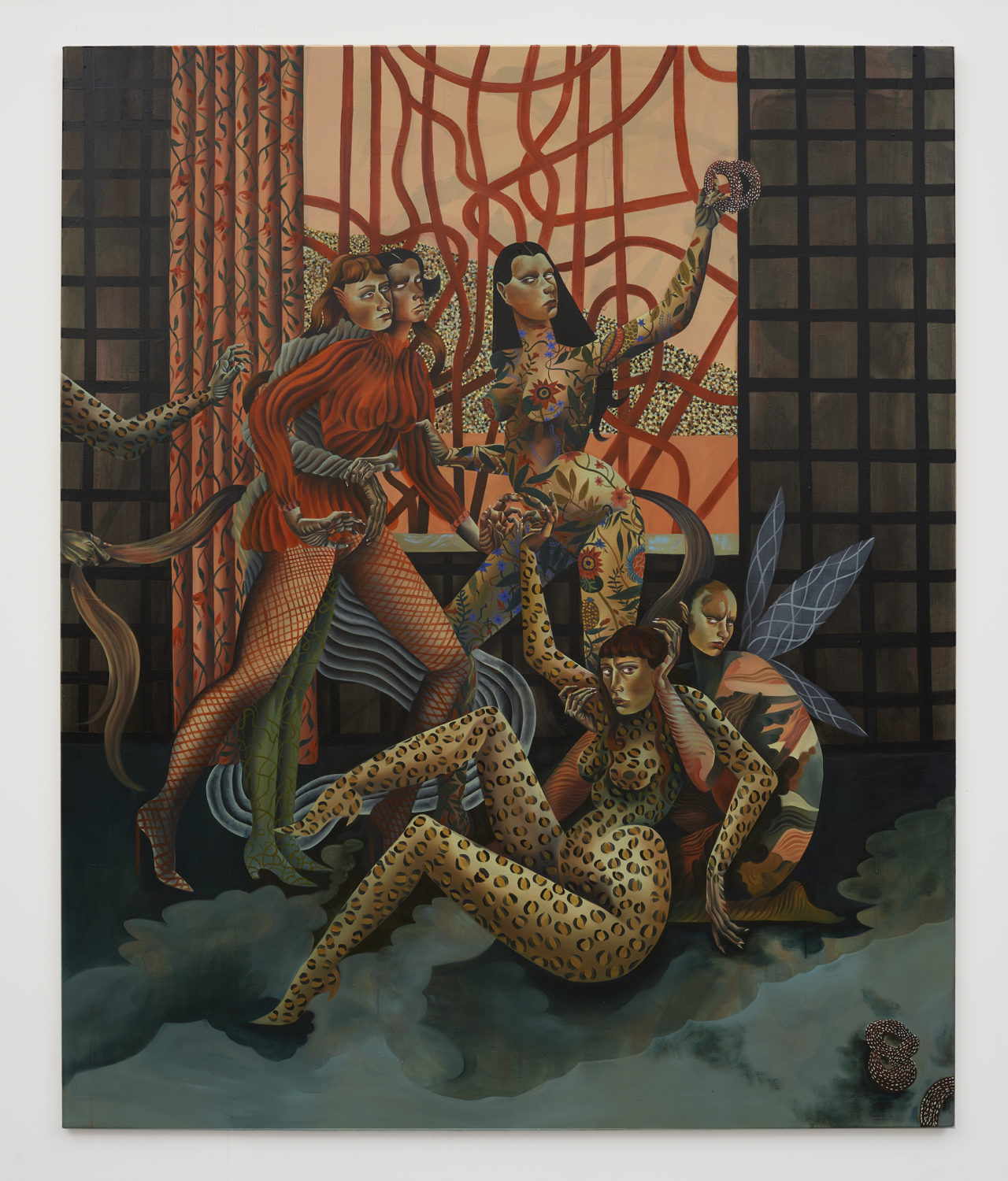

A successful painting to me is a surprise that I don’t quite understand, that makes me laugh because it knows something I don’t. My paintings in lots of ways sit in or reference the language of historical painting. But the figures have contemporary motivations and thoughts that perhaps didn’t even exist historically. I am curious about this disruption and how it can create new stories. I think about consequence or lack of, both from within and without the figures control, and their ownership of the moment they are seen in. Making the question of gaze not about the viewer or maker’s gaze, but that of the figures in the paintings, as if we have a glitch between our worlds and can see each other for a split second.

SC: Can you tell us about the selection of paintings included in your exhibition, Something Vexes Thee?, at François Ghebaly Gallery?

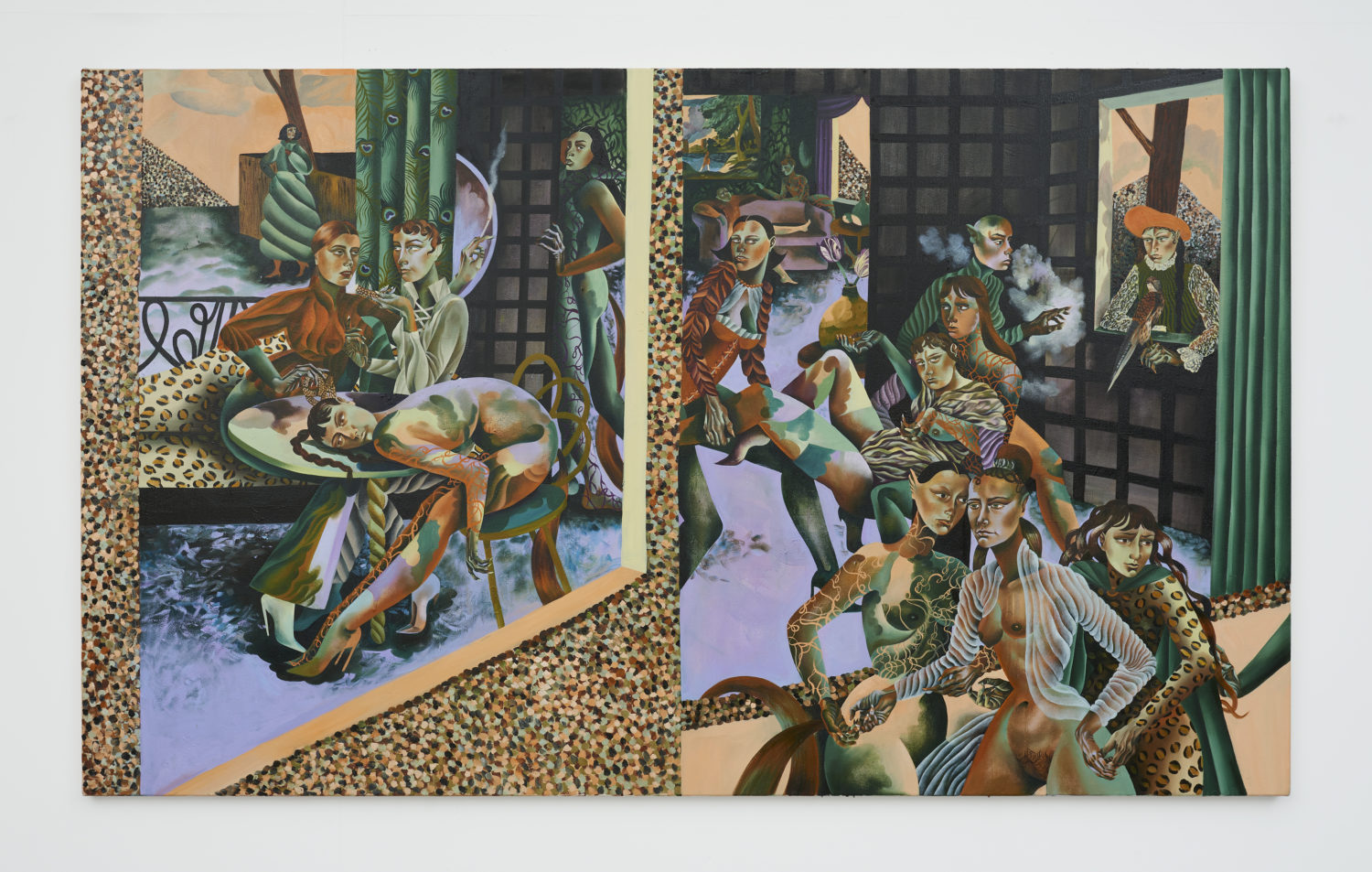

JM: The title of the show takes its name from the painting Something Vexes Thee?. It comes from a scene in Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves. The Sheriff of Nottingham is raging about Robin Hood messing up his plans, so he goes to see his witch in the cellars of the castle. He’s going around smashing stuff up and the witch asks Alan Rickman, “Something vexes thee?”, which makes me laugh. I love tantrums. Not actual tantrums, but the idea of them. That one person considers something so trivial and the other considers it worth screaming about. It also felt very much of the pandemic where we are juggling our own and all our friends’ mental health and wellbeing constantly. I am interested in hysteria and the gendered notions of it, as well as this dismissiveness, trivialising and resulting exasperation. A disinterest in taking others’ problems seriously, but in medieval phrasing.

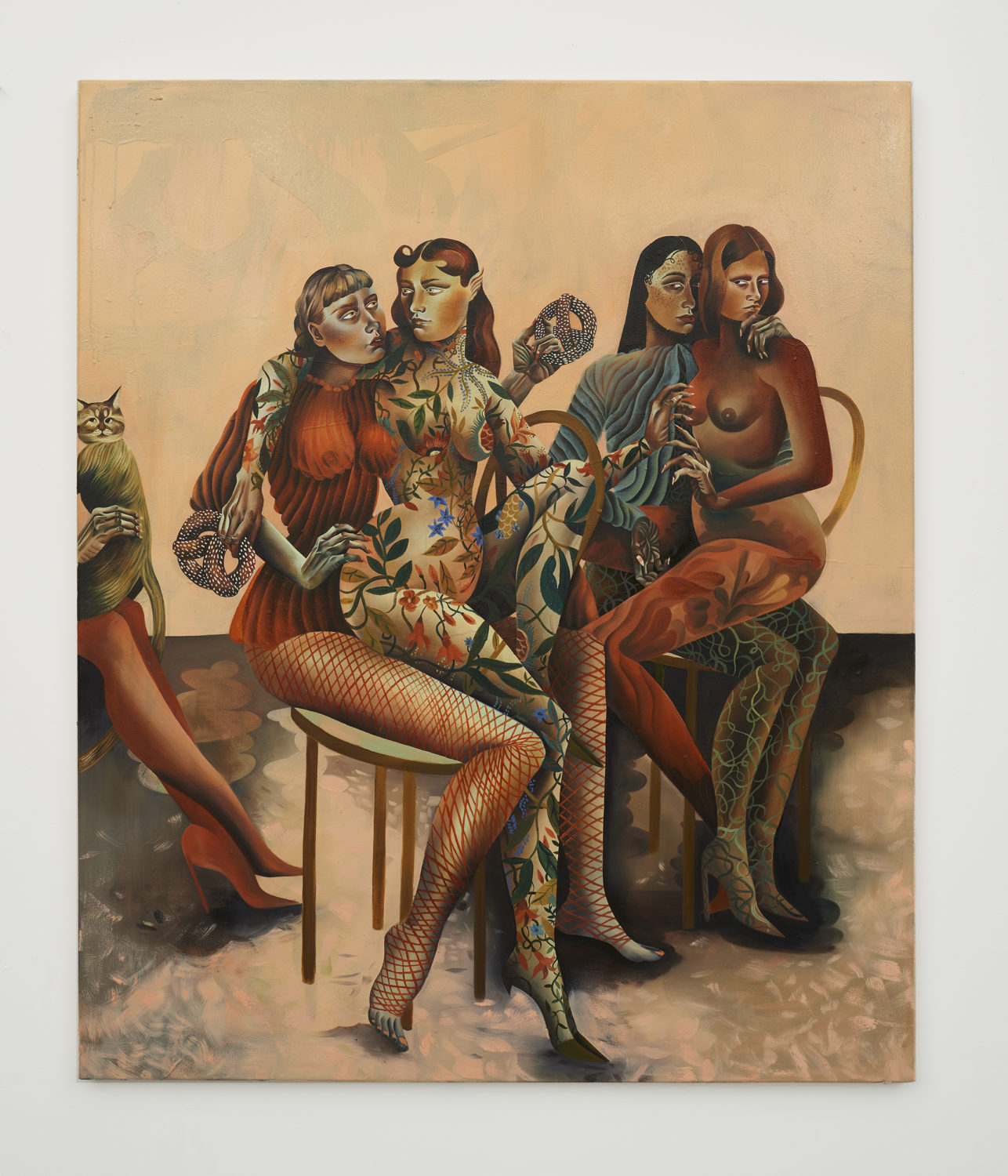

The figures on the right of this painting are busy. Pointing fingers, organising, standing still, getting nothing done. I was thinking about gossip and the way the meaning has changed over time. It used to mean a good friend, usually a woman, but came over time to mean idle talk and rumour. The verb “to gossip” first appears in Shakespeare. It’s another gendered word. But gossiping is fun, it’s storytelling and it’s playful but of course also has its nasty side. Are the figures in the back playing cards or tarot, divining or gambling? Asking chance questions either way. I like the relationship between divination and gambling and how both are putting something out there for a response. They show how the figures are always bothering each other, are they helping or hindering?

In The Closer Knife the title is something taken out of context which adds a layer of narrative. I am interested in not describing the painting but adding or sometimes trolling it. My titles in general come from overheard conversations, misunderstandings, books, TV and film. Anywhere but often misused rather than referenced. I like that one title can be whimsical or taking the piss, the next romantic, serious, angry or hopeful. I like the titles to build together to create a certain feel or a bad poem. The title for the painting Don’t Bite Anybody Else comes from the TV show The Undoing, when Hugh Grant’s solicitor tells him not to bite anybody else’s ear off. In the context of the painting, it seems possessive. Like a soft bite. Like don’t kiss anybody else. But also like a scolding. The figures in the painting don’t really look like they will be possessed or told what to do. They look very comfortable doing what they are doing. But there is also the cat.

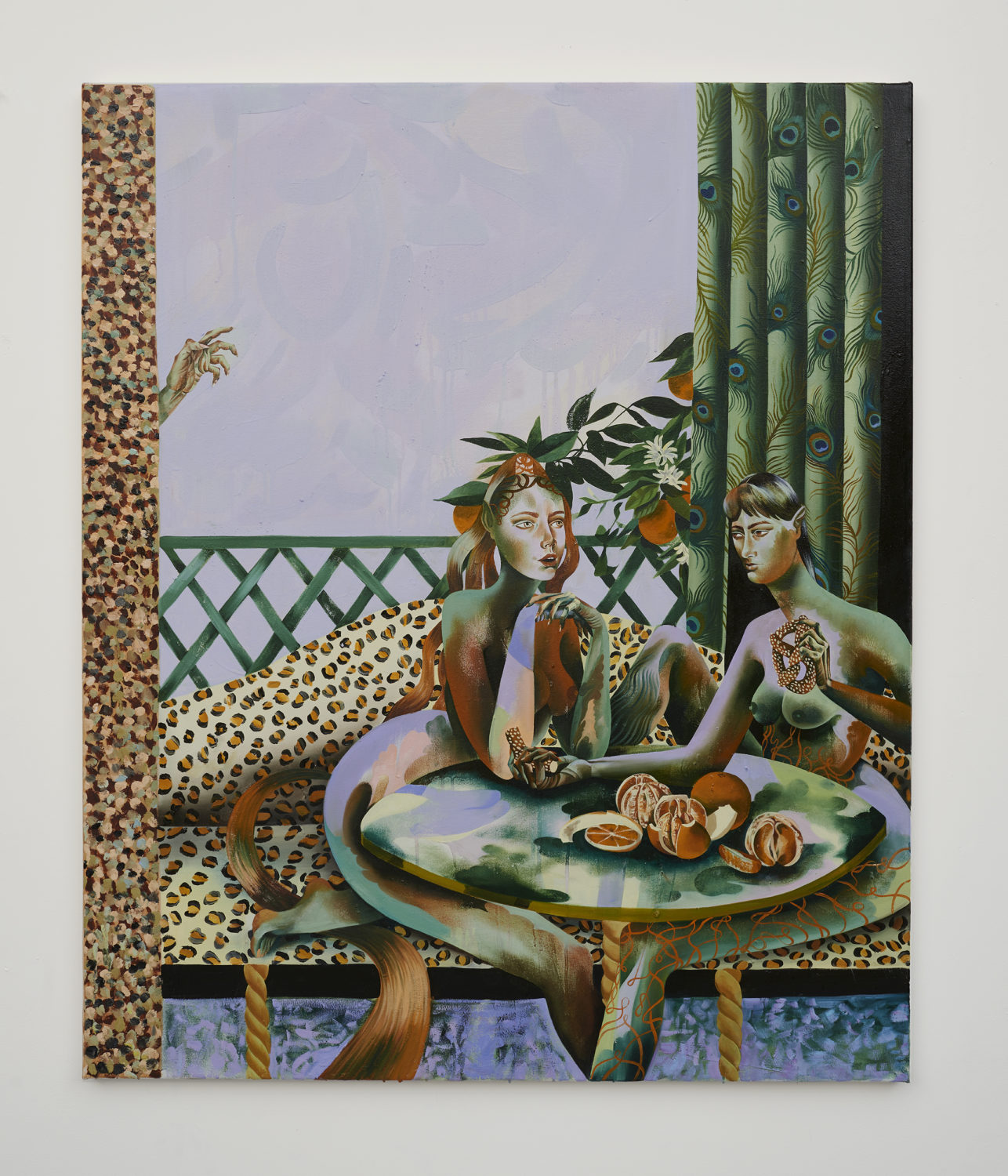

Le Crunch comes from an estate agent on Come Dine With Me, bragging about his prowess in the kitchen. I like the mix of French and English and the grandifying of the word “crunch.” I also felt like this painting was a fake French painting. In Le Crunch I was thinking about a breeze travelling through rooms telling stories and whispering to change events. There is a scene in Maggie O’Farrell’s book Hamnet where an androgynous figure comes out from the woods carrying a falcon, reminding me of Orlando, a figure I think about often in relation to my work. In the painting titled Your Leafish Light I was curious about the seam that runs between the two figures. Where they are touching and where the blue comes through. I like to put figures heads together; I think about the closeness of coming-of-age friendship. But also, of couples who are a unit. And when you speak to one of the two it’s like you are speaking to the pair and they share knowing glances that are extremely private in a public space. We have of course grown up in the era of the individual; I’m curious as to other ways of living and how sci-fi and fantasy can have these conversations and imagine a post-humanist future.

SC: You work with a very distinctive palette — could you expand on your use of colour?

JM: My use of colour is led intuitively and informed in part by the underpainting I make on the surface of the canvas. The palette is decided before I start and goes a long way to set the scene. It also has great narrative and associative power. Colour suggests things to me. It suggested the pretzels in Something Vexes Thee?, the fishnets in Don’t Bite Anybody Else and the direct gazes in Your Leafish Light. In a practical sense I make a kind of nonsense of colour. The figures, and spaces are made up of the same colours, so I use colour and pattern to differentiate one form from another. With the inside outside nature of these paintings, colour, pattern and clothing are important in allowing the figures to take up room in public space and take ownership of space in general.

SC: What are you working on at present and how has the pandemic affected your way of operating?

JM: I’m currently working on a solo show with Lyles and King in October as well as a few group shows and fairs. I’m extremely lucky to have had space to myself at my studio to be able to keep working and get out of the house.

SC: What do you want to learn more about?

JM: First, I’d like to read the pile of books I have waiting. Then gambling, chance and divination. Tricksters, the fool and games. The stage and theatre. And the relationship between humans and animals historically in our cultural imagination.

Feature image: Jessie Makinson, Something Vexes Thee?, 2020. Courtesy of the Artist, François Ghebaly, Los Angeles, and Lyles and King. Photo: Paul Salveson