Interview: Architect Takero Shimazaki On Making The Personal Collective

By Something CuratedHailing from Tokyo, Japan and raised in the UK, London-based architect Takero Shimazaki co-founded the practice t-sa with Yuli Toh back in 1996. Today, at the atelier’s helm alone, Shimazaki’s approach to design continues to be rooted in a preoccupation with context, always considering the existing built fabric, details and landscape, as well as the stories and narratives of a space’s inhabitants. Having taught for five years at London’s Architectural Association and most recently, The Cass, London Metropolitan University, Shimazaki has established his own school of architecture, t-sa forum, exploring alternative modes of architecture education, primarily focussed on practice. From the meticulous refurbishment of domestic spaces and listed buildings, to thoughtful new build residential and public projects, t-sa seeks to create timeless architecture with clarity and sensitivity. To learn more about Shimazaki’s career, the thinking behind t-sa’s approach, and what the studio has planned next, Something Curated spoke with the architect.

Something Curated: Can you give us some insight into your background and how you entered the field of architecture?

Takero Shimazaki: I grew up in Tokyo, Japan and lived there until I was 13. Our family moved to the UK when my father decided to work for the BBC. It was a big cultural shift for me and I enrolled into a school in Kent. My grandfather was an architect in Tokyo and had worked on a number of buildings around the Marunouchi district and others. I think he was one or two years below Kenzo Tange at the architecture department of Tokyo University. I first encountered architecture as a profession through him. I became very aware of his work when he designed our house when I was about 10. I remember being fascinated on the construction site – where my mother was talking with an architect (must have been my grandfather’s team member) over a drawing, discussing where the kitchen or the bathroom would go – when all I could see was a timber structural skeleton. The idea of imagining spaces when they still only existed on drawings gripped me very much.

As well as getting to know a little bit of what he actually did at work, I really enjoyed talking to him and hearing many stories of his travels, hobbies, and the people that he had met through his work. We used to enjoy looking at a world atlas together and he would be talking about different countries and cities that he had visited – including his encounter with Picasso at his studio in France, which was very memorable for me. So, I thought this profession of architecture sounded like an exciting job, where you get to do and enjoy a variety of things and experience life-long learning. Later on, when I was studying architecture, and then began practising – we could finally discuss the subject much more specifically, each time I returned to Tokyo to see him. That was very enjoyable.

After studying in Cardiff and the Bartlett UCL, I was very fortunate to work for Itsuko Hasegawa (in Tokyo), Richard Rogers, and later on for Peter Smithson. I learnt so many things from them and their teams. I am very grateful to Yuli Toh, who first employed me and then invited me to be a partner to co-found t-sa. She has since left the practice, but her teachings and attitudes are very important to the current studio and our way of working today.

SC: How would you describe the ethos of t-sa?

TS: I don’t know if it is the ethos as such, but we have always been conscious of the fact that as architects, we work with places, sites and buildings that already exist. Even for new build projects, we are interested in the existing landscape, the journey to and from that site, the context and so on. We also very much value each of our inspiring clients’ and end-users’ ideas, visions, and their dreams. All of these factors continue to fuel my interest in the relationship between something specifically personal or subjective, and the collective. I think it is beautiful when personal feelings can be shared or acknowledged collectively. The juxtaposition of personal interests (whether by our clients, end-users or ourselves), specific particular site context or history, in conjunction with more universal collective memory, architectural language and communal interests, are explored in each project.

Any two projects are never the same for this reason. Each project is always very specific to these conditions and we don’t work with a defined overarching t-sa language as such. If there are some common threads through the projects, then that is great. But we enjoy witnessing how projects develop out of sometimes coherent and sometimes dialectic sets of subjective and generic ideas. For example, for our project at the Barbican, the clients, who lived in Japan for many years, wanted to create an apartment that is very much rooted to traditions of Japanese architecture. And all this within a very specific Modernist context of the Shakespeare Tower at the Barbican Centre. We had never designed with the language or details of traditional Japanese architecture prior to this and we enjoyed the challenge very much. Yet, against this background, we hope that our own personal and atmospheric gestures are present in the spaces.

SC: Could you expand on your approach to using materials?

TS: Every material carries with it its own specific properties of course. We have always been interested in working with these inherent properties in ways to amplify the emotional qualities through spatial arrangements. Whether its brick, concrete, timber, or plastic – they all have their own beautiful nature. The idea of economy in the use of materials interests us. Most of our projects are working with existing conditions and the materials we find. Naturally they contain notions of historical, cultural and social contexts. Refurbishing, renovating, re-using and renewing buildings through thinking about existing materials teaches us to think carefully about their meanings. Textures and construction details can tell a lot about the architectural intent – historical, cultural, economical, social and emotional. More recently, our interest in what we can do with economical materials such as plywood, plasterboard or MDF for example has become important. Not always out of choice but through necessity too. We think about how these simple and standard materials can be loaded with emotive, atmospheric qualities – and how materials like these can generate architectural language and contribute to public life. In many situations, we tend to enjoy the archaic qualities in the materials, in their less polished states.

SC: How do you think about storytelling through your spaces – for example in the aforementioned apartments you renovated in Barbican’s Shakespeare Tower?

TS: I am not sure if we are conscious of storytelling in our projects, but it is an interesting question. By being raw and sincere with the subjective interests, overlaid with research and understanding certain architectural languages or construction methods that we work with, I hope that narratives exist in the spaces. In the case of the Barbican project, we were interested in the period of Modernism in Japan where a strong interest in historic Japanese architecture was still present in a more obvious less abstract way. Works of Seiichi Shirai, Kazuo Shinohara, and Kenzo Tange were studied. We particularly enjoyed the raw co-existence of European classicism, international modernism, and Japanese tradition in Shirai’s work. We debated topics at length, including for example the symbolic use against the structurally-honest use of columns. We could also share interesting conversations with the clients about how certain detailing reminded us of different post war periods in Japan. For example, the tiling of the kitchen floor, together with the exposed concrete of Shakespeare tower and the timber screens very much reminded us of early Shōwa or Taishō eras. Then, there is of course the story of the original Chamberlin, Powell and Bon architecture that was carefully refurbished and integrated into the spaces.

SC: What are you working on at present and how has the pandemic affected your way of operating?

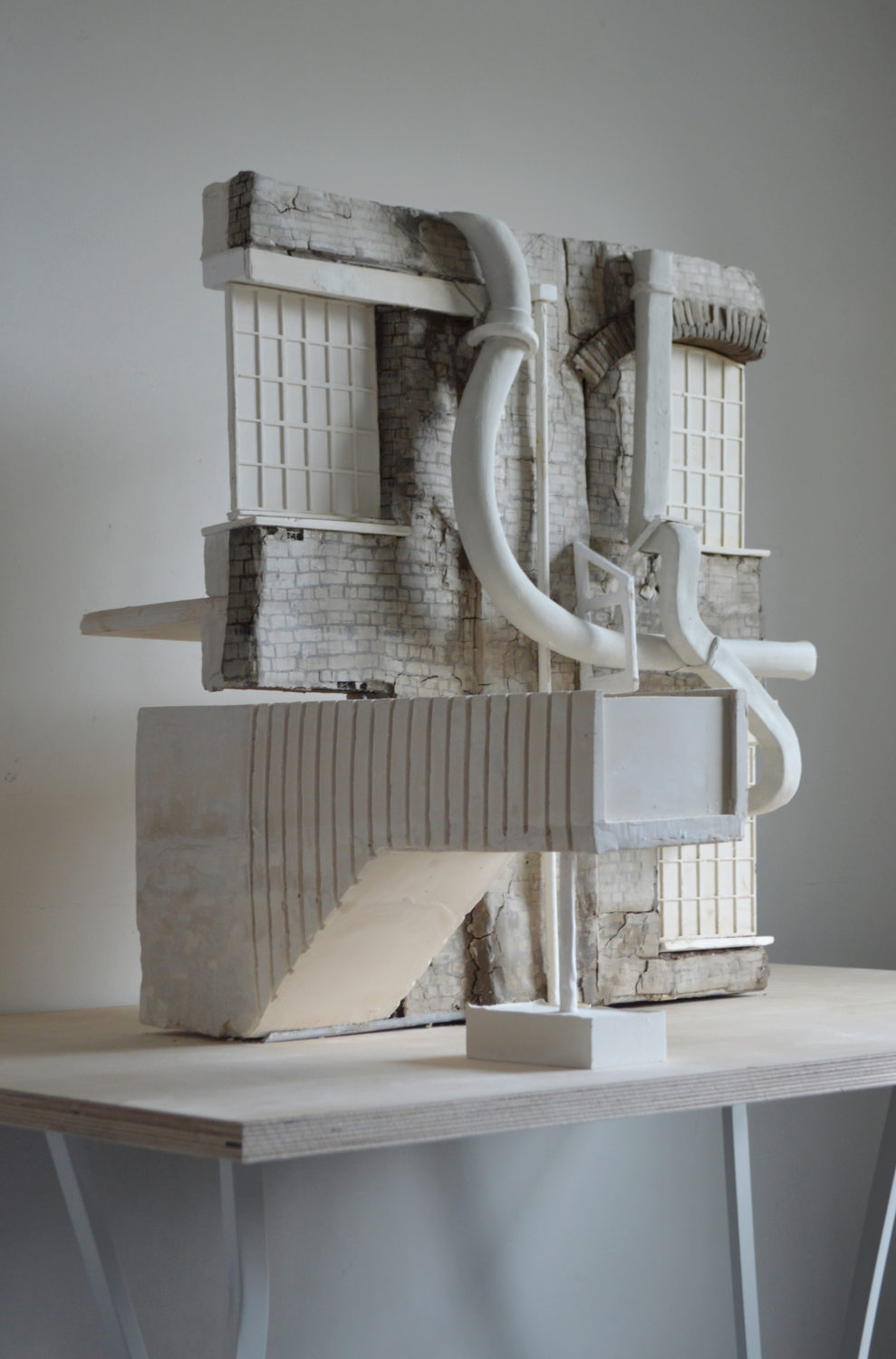

TS: At the moment, we are working on cultural projects such as a new theatre in Hackney Wick, The Royal Academy of Dance headquarters, another cinema for Curzon in Camden, estate wide projects in Lincolnshire with a Palladian Manor, and some new and refurbished houses. Related to the topic of materiality, for the theatre project, we are interrogating playful notions of fakery, temporality and permanence in the way elements work together and are constructed. The pandemic has really amplified our collective desire for spaces for direct performances and illusions such as theatres, dance studios and cinemas. The pandemic has of course forced us all to work from home. I am personally drawing more. It has given me extra time, focus and space to draw and enjoy working with hand drawings. The studio space is used for model making with so much more space to manoeuvre than before. And the site visits have become these rare, exciting excursions out of our homes – precious moments for direct physical contact with construction and places.

SC: Teaching has been a central part of your output for years – what motivated you to establish your own school?

TS: Teaching is an absolutely important part of what we/I do. It helps us to keep learning. Each year, from setting the brief through to taking those themes from research to output, we value the conversations with our students, colleagues and invited guests. I started t-sa forum (our own school) early on in my teaching career because I felt that there must be an alternative set up to teach architecture that is more directly related to the practice of architecture and the involvement of wider team specialists such as consultants, contractors, artists, clients and manufacturers. Because the course wasn’t related to ‘qualifications’, we were able to do what we wanted, working with whoever we wanted and exposing the students more directly to the practice and the art of architecture. It also meant there was no hierarchy of student’s qualification levels. A first year student would be on the same course with a postgraduate student or even a practitioner who wanted to study again.

Currently, I am however enjoying teaching at London Metropolitan University, Diploma school. For the past few years, we have been focusing on public architecture of economy, re-use and subjectivity. This year, our focus has been on Spitalfields – looking at a renovation project of a Georgian house on Princelet Street with the collective Assemble, and the re-use of The Old Truman Brewery for public benefit. Ideas that we recently discussed in our student reviews such as “almost doing nothing” or architecture is at the “age of interventions” are interesting and set up great challenges for us today. We always start the thesis project by teaching the students how to observe and survey the existing situation. Existing resource is already a vast proportion of the proposal. We have to pursue to work with what we have and adapt things to what we need, through retention, subtraction, addition, alteration etc. Our students’ work shows that incredibly creative and exciting future city life is possible through interventions and doing just enough.

SC: What are you currently reading?

TS: I have a few books open, but enjoying Sarah Schulman’s The Gentrification of the Mind – Witness to a Lost Imagination. It was recommended to me by the artistic director of our theatre project in Hackney Wick. It is about the gentrification of Lower East Side, New York related to AIDS and how the entire community of artists, immigrants and outsiders were erased. Gentrification is a complex topic but something we have to seriously deal with – not only, but particularly as architects. Another book that I am in and out of is The Years by Annie Ernaux. It is a beautiful new form of a collective autobiography through subjective and social reflection on twentieth century French history. The format of the book is very unique and original. I enjoy the calm, consistent, rhythmic tone of the storytelling, filled with rich and vibrant events of each moment from the past. I see many parallels with architectural space-making.

Feature image: Shakespeare Tower apartment, Barbican, London. Photo: Anton Gorlenko / Courtesy t-sa