On The Origins & Evolution Of Polynesian Literature

By Something CuratedThe diverse peoples of Polynesia, a grouping of Central and South Pacific Ocean island archipelagos, together with those of the scattered cultures known as the Polynesian outliers, speak languages and dialects that descend from a language thought to have first been spoken in the Tonga and Samoa areas around 1000 BCE. Polynesia’s mythologies and maritime narratives emanate from rich oral traditions; the various cultures each have distinct but related oral customs, that is, legends or myths traditionally considered to recount the history of ancient times and the adventures of gods and deified ancestors. The accounts are characterised by an extensive use of allegory, metaphor, parable, hyperbole, and personification. Interestingly, many of the cultures share similar tales, with colourful mythologies often slightly reworked by various communities, depending on the region.

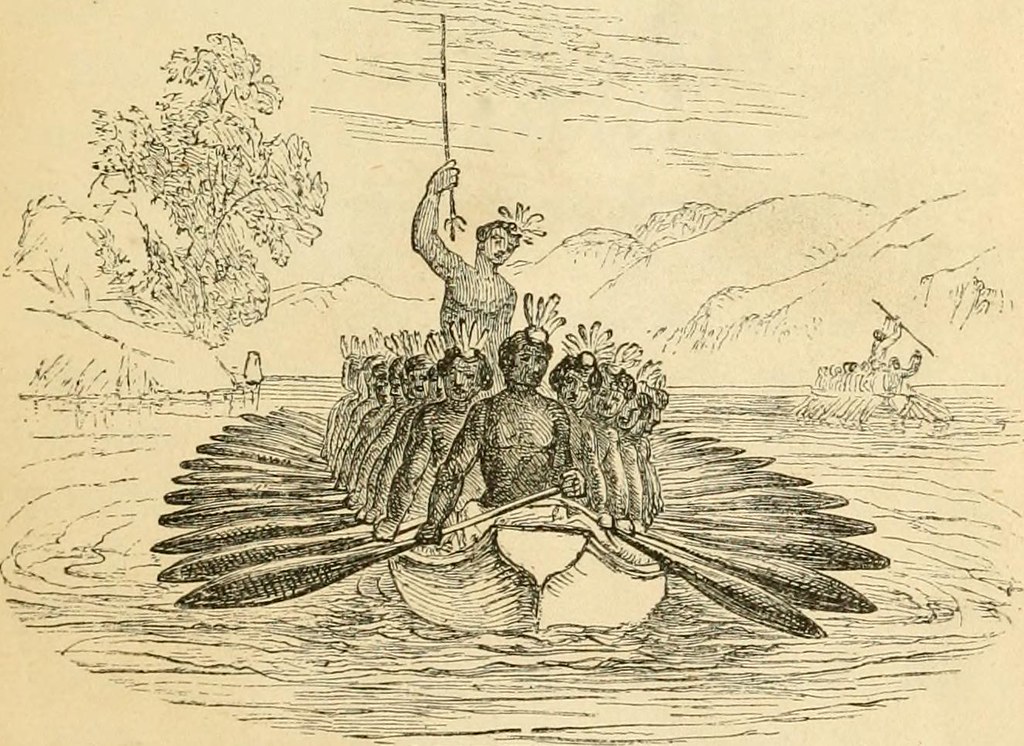

There is most often a story of the marriage between Sky and Earth; the New Zealand version, Rangi and Papa, is a union that gives birth to the world and all things in it. There are stories of islands pulled up from the bottom of the sea by a magic fishhook, or thrown down from heaven. There are tales of voyages, migrations, seductions and battles, as one might expect. Stories about a trickster, Māui, are widely known, as are those about a beautiful goddess Hina or Sina. In addition to these shared themes in the oral tradition, each island group has its own stories of demi-gods and culture heroes, shading gradually into the firmer outlines of remembered history.

Orality has an essential flexibility that writing does not allow; in an oral tradition, there is no fixed version of a given tale. The story may change within certain limits according to the setting, and the needs of the narrator and the audience. Contrary to the Western concept of history, where the knowledge of the past serves to bring a better understanding of the present, the purpose of oral literature is rather to justify and legitimatise the present situation. An example is provided by genealogies, which exist in multiple and often contradictory versions. The purpose of genealogies in oral societies generally is not to provide a true account, but rather to emphasise the seniority of the ruling chiefly line, and hence its political legitimacy and right to exploit resources of land and the like. Each island, each tribe or each clan will have their own version or interpretation of a given narrative cycle.

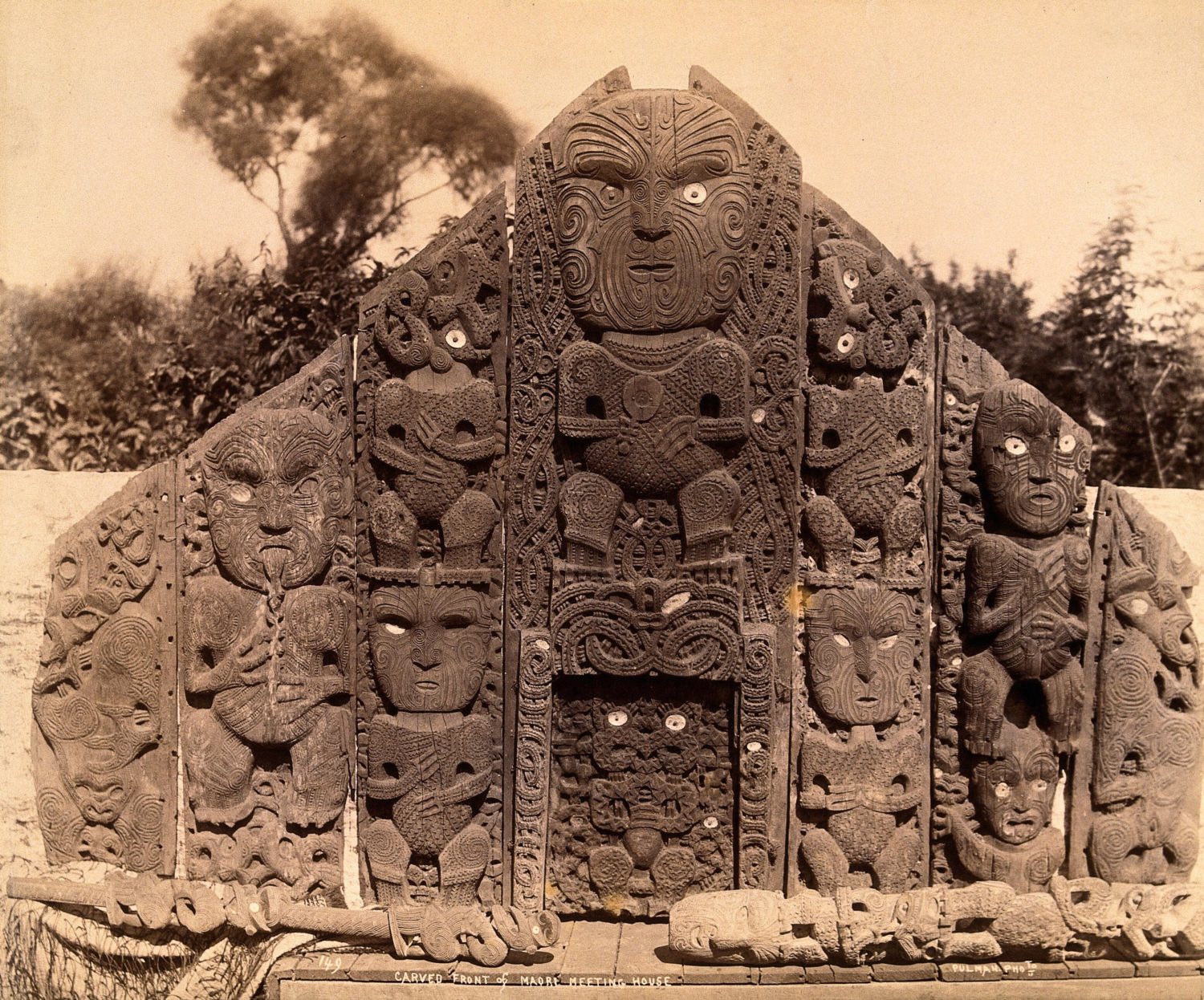

This process was disrupted when writing became the primary means to record and remember the traditions. When colonisers, missionaries, officials, anthropologists or ethnologists collected and published these accounts, they inevitably changed their nature. By fixing forever on paper what had previously been subject to almost infinite variation, they fixed as the authoritative version an account told by one narrator at a given moment. In New Zealand, the writings of one chief, Wiremu Te Rangikāheke, formed the basis of much of Governor George Grey’s Polynesian Mythology, a book which to this day provides the de facto official versions of many of the best-known Māori legends.

Some Polynesians seem to have been aware of the danger and the potential of this new means of expression. As of the mid-19th century, a number of them wrote down their genealogy, the history and the origin of their tribe. These writings, known under the Māori name of “pukapuka whakapapa,” translated to English as “genealogy books,” or in tropical Polynesia as “puta tumu,” origin stories, or “puta tūpuna,” ancestral stories, were protectively guarded by the heads of households. Ultimately, many disappeared or were intentionally destroyed by ruling powers. Today, these largely illusive ancestral accounts, along with Polynesia’s enduring mythologies continue to inspire authors of the region and diaspora, providing a compelling foundational narrative on which to build upon.

Reflecting on contemporary fictional writing from French Polynesia, New Zealand and Samoa, literary scholar Chloé Angué writes: “When they create characters or stories which exalt the history of their migrant ancestors, Polynesian writers reclaim their past. They also keep alive and help spread the memories of the maritime journey. Most of all, they “write back” to those who ignored their heritage or failed to recognize its value, thereby giving the myth of the original migration a political dimension. In their novels, the quest of the hero is filled with the memory of the great migration, which adds to the postcolonial protest discourse. The myth is nevertheless seldom used for concrete political demands: most of the time, it echoes an ideal or dream of a new world, a world where Polynesian cultures and literatures would be recognized for their universality and creativity.”

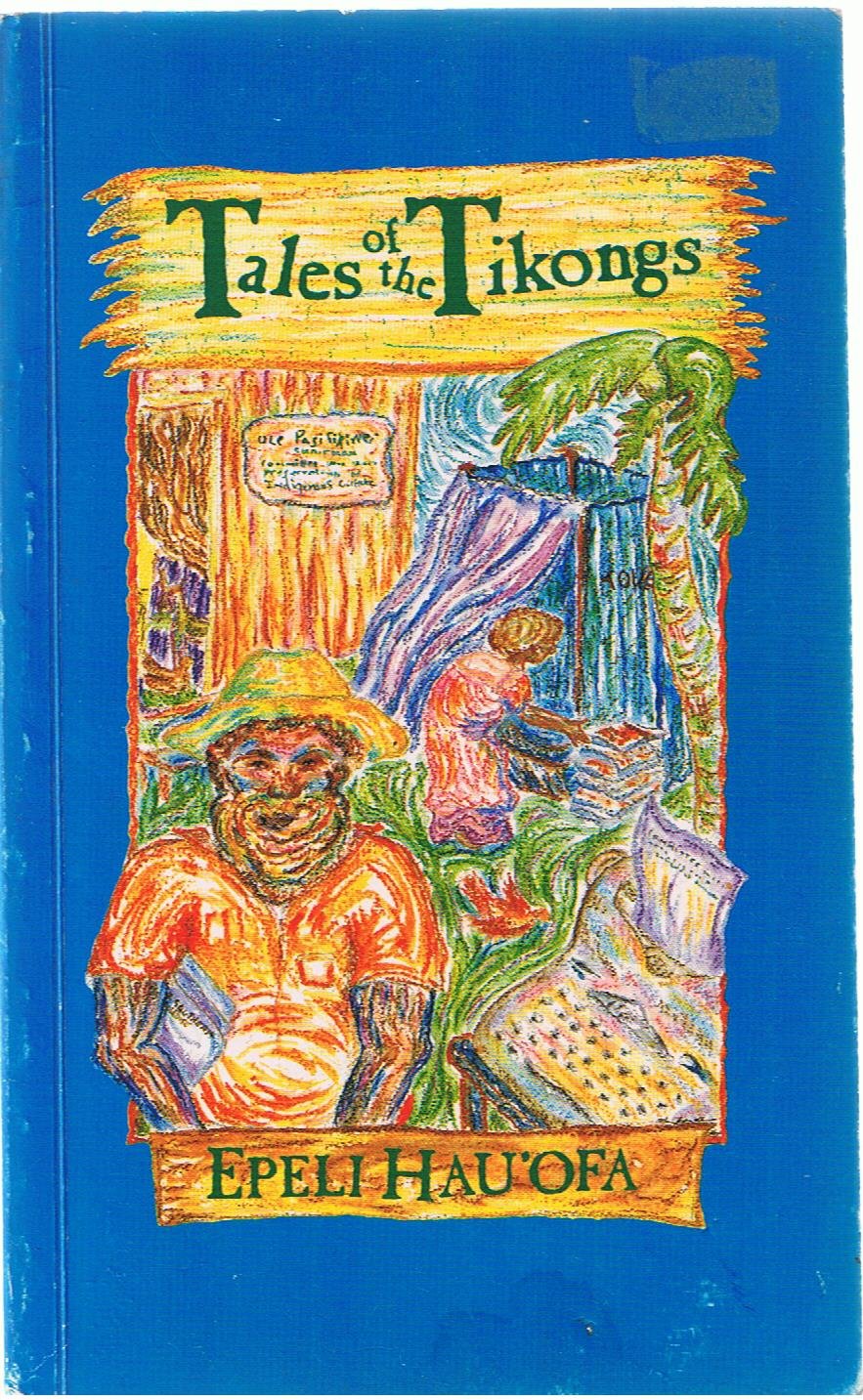

In his collection of stories, Tales of the Tikongs, Epeli Hau’ofa examines the significance of ancestors in the South Pacific, and the perils that colonialism brings to tradition. Hau’ofa sets the stories on an imagined island in Oceania called Tiko, where the culture, society, and politics are akin to his home country of Tonga. Along with his contributions to the South Pacific literary canon, Hau’ofa has been instrumental in the art scene of Oceania, establishing the Oceania Centre for Arts at the University of the South Pacific. Black Marks on the White Page, edited by Witi Ihimaera and Tina Makereti, is a curated anthology that pushes the boundaries of the short story genre. Each indigenous Oceanic author selected for the project brings innovation to the art of storytelling, whether it comes in the form of verse or prose or even visual representations.

Poet and performer, Kathy Jetn̄il-Kijiner utilises art and activism as a way to inform her readers and audiences about her home, the Marshall Islands. In 2012, she co-founded Jo-Jikum, a non-profit organisation committed to helping the next generation of Marshallese to preserve their islands in the face of rising sea levels. Her book, Iep Jaltok: Poems from a Marshallese Daughter, draws from familial stories and experience to create a collection of poetry about Marshallese politics, heritage, and climate change. Lani Wendt Young, known for her young adult novels set in Samoa, takes on the heavier aspects of life in her acclaimed collection of short stories, Afakasi Woman. With prose that have cemented her place as a prominent South Pacific writer, Young shares 24 short stories that intelligently oscillate between the light-hearted and arduous experiences of a Samoan woman.

Bibliography:

Chloé Angué, ‘The Narrative and Poetical Role of a Polynesian Literary Myth: Canoes of the Origins in Contemporary Texts from French Polynesia, New Zealand, and Samoa’, ab-Original Vol. 2, No. 1, 2018, Penn State University Press

Martha Beckwith, Hawaiian Mythology, 1940, Yale University Press, re-issued in 1970 by University of Hawaii Press

Frances Yackel, ‘13 Books by Pacific Islanders’, 2019, Electric Literature

Robert D. Craig, Dictionary of Polynesian Mythology, 1989, Greenwood Press, New York

Feature image: Aline Amaru, Tahiti, b.1941, La Famille Pomare (tifaifai) (Pa’oti style), 1991. Courtesy Queensland Art Gallery Foundation