From Poetry To Politics, Meet 2021’s Jameel Prize Finalists

By Something CuratedThe Jameel Prize, the world’s leading award for contemporary art and design inspired by Islamic tradition, was established by the Victoria & Albert Museum and Art Jameel in 2009. Attracting a diverse roster of applicants from around the globe, this year eight finalists have been shortlisted for the sixth edition of the award. Their work will be on display in the exhibition Jameel Prize: Poetry to Politics at the V&A this autumn, and the winner will be announced on 15 September 2021. With compelling practices spanning graphic design and fashion, typography and textiles, installation and activism, the finalists engage with both the personal and the political, interpreting the past in creative and critical ways. Following the London presentation, the show will tour internationally, spotlighting the work of the eight finalists from India, Iran, Lebanon, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, the UAE and the UK. Ahead of the exhibition’s launch, Something Curated takes a closer look at this year’s shortlisted creatives.

Golnar Adili (Iran)

Golnar Adili is a multi-media artist and designer based in New York. Her practice explores aspects of her identity, particularly through Persian language and poetry. Growing up in Tehran after the 1979 Revolution, Adili’s early life was characterised by separation, uprootedness and longing. The work that will be on display in the Jameel Prize – Ye Harvest from the Eleven-Page Letter, 2016 – explores a letter from her father, who was exiled from Iran when Adili was young, to his lover. Adili transforms the letter into a spatial installation, honing in on his use of a single letter from the Persian alphabet — ye — which becomes the consistent motif of the piece. By precisely reproducing the idiosyncrasies of his handwriting, and the distance between each ye, Adili encodes the original document in three-dimensional form. The installation, both monumental and delicate, pays homage to her father, and abstracts and obscures the emotional content of his communication.

Hadeyeh Badri (UAE)

Hadeyeh Badri is an Emirati designer and textile artist who lives and works in Dubai. For Badri, textiles offer a rich creative language – one that unites gesture, touch, memory, and ritual. Three of her complex and colourful weavings will be on show in the Jameel Prize, all of which incorporate writing into the body of her fabric. In these works, such as Prayer is my Mail, 2019, Badri nods to the legacy of the Jacquard loom in the invention of coding, but the pieces feel more intimate than algorithmic. The texts Badri uses are personal, taken from the diary of her beloved late aunt. She uses weaving as a way of reconnecting with her aunt, and calls upon a trope in pre-Islamic poetry, al-wuquf ‘ala al-atlal (‘standing by the ruins’), in which a poet visits a site of mourning or of architectural decay and reanimates its history through language. Badri hints at the notion that weavings may act as personal monuments, ones that remain deliberately partial and under construction.

Kallol Datta (India)

Kallol Datta is a clothing designer from Kolkata, India, whose interest in clothing from North Africa and West Asia emerged during a childhood spent in the UAE and Bahrain. Datta discovered a Senegalese caftan in his grandfather’s wardrobe that prompted research into garment traditions from across Asia, the Middle East, the Indian subcontinent and the Korean peninsula. Datta mines the shapes and silhouettes of the abaya, manteau, hanbok, hijab and caftan, combining gestures of enveloping, swaddling, wrapping and layering in contemporary configurations. His approach to pattern-cutting is experimental, skewing traditional geometry to create sculptural silhouettes, brought to life on the body. Datta notes, “Clothes-making is an exercise in anthropology for me”, acknowledging the power of clothing to challenge social norms and channel personal expression.

Farah Fayyad (Lebanon)

Farah Fayyad is a Lebanese graphic designer and printmaker, shortlisted for the Jameel Prize on the strength of two projects. The first is typographic: fascinated by Arabic calligraphy and lettering, Fayyad designed a contemporary Arabic typeface, Kufur, based on historic Kufic script. Her re-imagination retains Kufic’s visual character while adapting some features for digital use. The second project emerged from the politics of the present. Fayyad is passionate about screen-printing and runs a small press in Beirut. In October 2019, popular uprisings began across Lebanon and hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets to protest government corruption and a growing economic crisis. Fayyad and her colleagues set up a screen-printing intervention at the heart of the Beirut protests. They equipped a manual press with slogans and artworks by local designers and printed these onto the clothing of protestors, free of charge and on the spot. The spontaneous project brought Arabic typography into the public and political sphere at a critical moment in Lebanese history.

Ajlan Gharem (Saudi Arabia)

Ajlan Gharem is a multidisciplinary artist and mathematics teacher based in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. His work explores how Saudi communities understand and articulate their culture amidst globalisation and changing power dynamics. Gharem’s installation, Paradise Has Many Gates, 2015, is true to the design and function of a traditional mosque, but is made of the cage-like chicken wire used for border walls and refugee detention centres. Such material provokes anxiety, but also renders the mosque transparent and open to the elements. The installation’s transparency challenges the political authority that can underpin religion; the installation also seeks to demystify Islamic prayer for non-Muslims, tackling the fear of the other at the heart of Islamophobia. The mosque is welcoming to everyone, and the installation is accompanied by a public programme that invites people of all backgrounds to meet and spend time together.

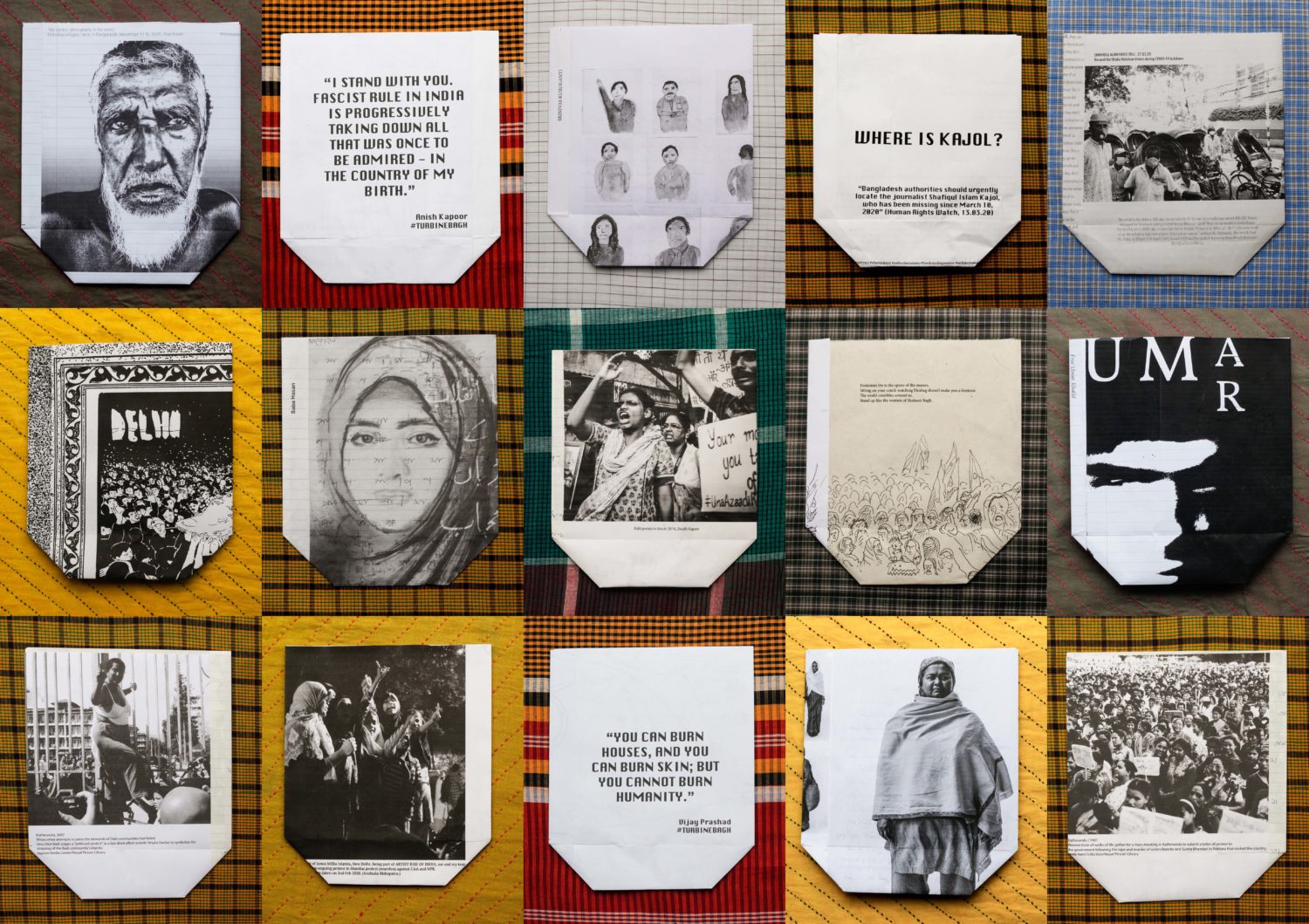

Sofia Karim (UK)

Sofia Karim is a British architect, artist and activist based in London. Karim’s activism work is centred on human rights, artists’ freedom of expression, and campaigns for political prisoners in India and Bangladesh. She is shortlisted for the Jameel Prize for her Turbine Bagh project, which imagines the Turbine Hall of Tate Modern as a stand-in for Shaheen Bagh, the neighbourhood in Delhi where mass protests against the Indian government’s Citizenship Amendment Act took place in December 2019. The Act offers amnesty to immigrants from three neighbouring countries to India, but excludes Muslims – part of an alarming rise in Islamophobic attitudes and legislation in India. “What we are witnessing is a vast and historic civil rights movement against fascism, Hindu nationalism and caste oppression”, says Karim. She invites artists and thinkers from across the world to engage with the struggle by designing samosa packets for Shaheen Bagh.

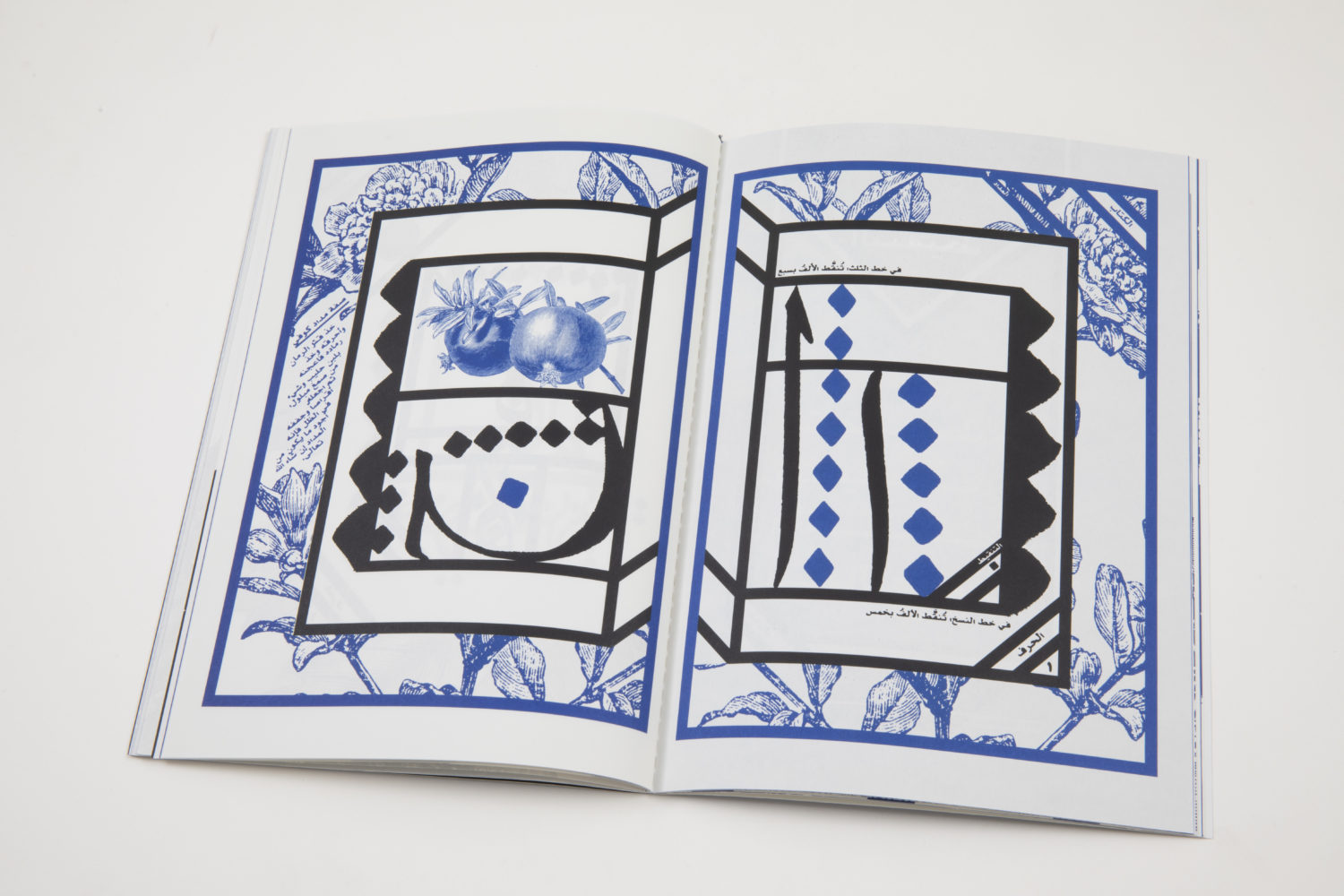

Jana Traboulsi (Lebanon)

Jana Traboulsi is a graphic designer from Lebanon. Her Kitab al-Hawamish (Book of Margins), 2017, is an artist’s book that investigates margins and marginalia in Arabic manuscript production. Stemming from research into Middle Eastern traditions of book-making, Traboulsi explores aspects of manuscript practices that are often considered secondary to the central text, including diacritics, Sura markers, the index, and catchwords. A ‘scar’ she found on an ancient piece of parchment – where the animal skin had been stitched closed and written around – inspired an emphasis on the materiality of the book as form. Traboulsi’s focus on the marginal extends to recitation: how language is formed and experienced in the body, from the brain to the diaphragm, larynx and mouth. Kitab al-Hawamish is a palimpsestic object whose annotated illustrations recall the scientific treatise.

Bushra Waqas Khan (Pakistan)

Bushra Waqas Khan lives and works in Lahore, Pakistan. She trained as a printmaker, but is known for the extraordinary garments she designs and makes in miniature. The catalyst for her creative practice is affidavit paper, or oath paper, which is used for all official documents in Pakistan. Affidavit paper often carries national emblems like the star and crescent alongside motifs and patterns from Islamic art and design. Contracts are printed and signed on this paper – it signifies authority and ownership, something kept safe over generations. For Khan, the manufacture of the affidavit stamp was similar to her practice of etching and printmaking, and she began to combine these processes with pattern-cutting and embroidery in the creation of miniature garments. The Jameel Prize will showcase the first spectacular dress Khan ever made, which is just 50cm tall.

Feature image: Ajlan Gharem, Paradise Has Many Gates – Daytime, 2015. Photograph: Ajlan Gharem