From Port-au-Prince to Paris: The Impact of Haitian Art on Surrealism

By Something CuratedIn 1945, French writer and poet, André Breton — the co-founder, leader, and principal theorist of surrealism — wrote about his first encounter with Haitian artist Hector Hyppolite’s paintings at the Centre d’Art in Port-au-Prince. “Haitian painting will drink the blood of the phoenix. And, with the epaulets of Dessalines, it will ventilate the world,” penned Breton in the gallery’s guestbook. Two years after his visit to Haiti, the exhibition, Surréalisme en 1947, co-organised by Breton and Marcel Duchamp in Paris, was filled with references to Haitian art.

Similar to Hyppolite, the paintings of Haitian artists like Préfète Duffaut, Castera Bazile, Fernand Pierre, Philome Obin, and Wilson Bigaud ingeniously permeate the familiar with the fantastical, characterised by rich visual storytelling. Their work often nods to Vodou rituals and customs during a time of Catholic dominance — a time when Haiti’s government was persecuting non-Christian beliefs. Delving further, Something Curated highlights the practices of four Haitian visionaries whose work influenced and ultimately helped revitalise surrealism.

Préfète Duffaut

Préfète Duffaut attended Centre d’Art, the pioneering school founded by DeWitt Peters in the mid-1940s. The artist draws on his connections to both Catholicism and Vodou, often employing motifs and symbols from both spiritual practices in his paintings. Having exhibited his work widely during his lifetime, an early career highlight was a group show of Haitian art at the Stedelijk Museum in 1950; and in 1968, he was awarded first prize at the World Festival of Black Arts in Dakar. He also contributed to the frescoes of the Episcopal Cathedral of Sainte-Trinité, which were tragically destroyed in the 2010 earthquake.

Fernand Pierre

Fernand Pierre, born in Carrefour, Port-au-Prince, began his artistic career as a wood carver before joining Centre d’Art in 1947, where he initially worked with ceramics before transitioning to painting. Pierre is renowned for his detailed depictions of nineteenth-century architecture and lush, colourful fruit-laden trees. Alongside Duffaut, he was one of the five artists who painted the famous murals of the Episcopal Cathedral of Sainte-Trinité in 1951. His work is featured in the permanent collections of several esteemed institutions, including the Musée d’Art Haïtien du Collège Saint-Pierre in Port-au-Prince.

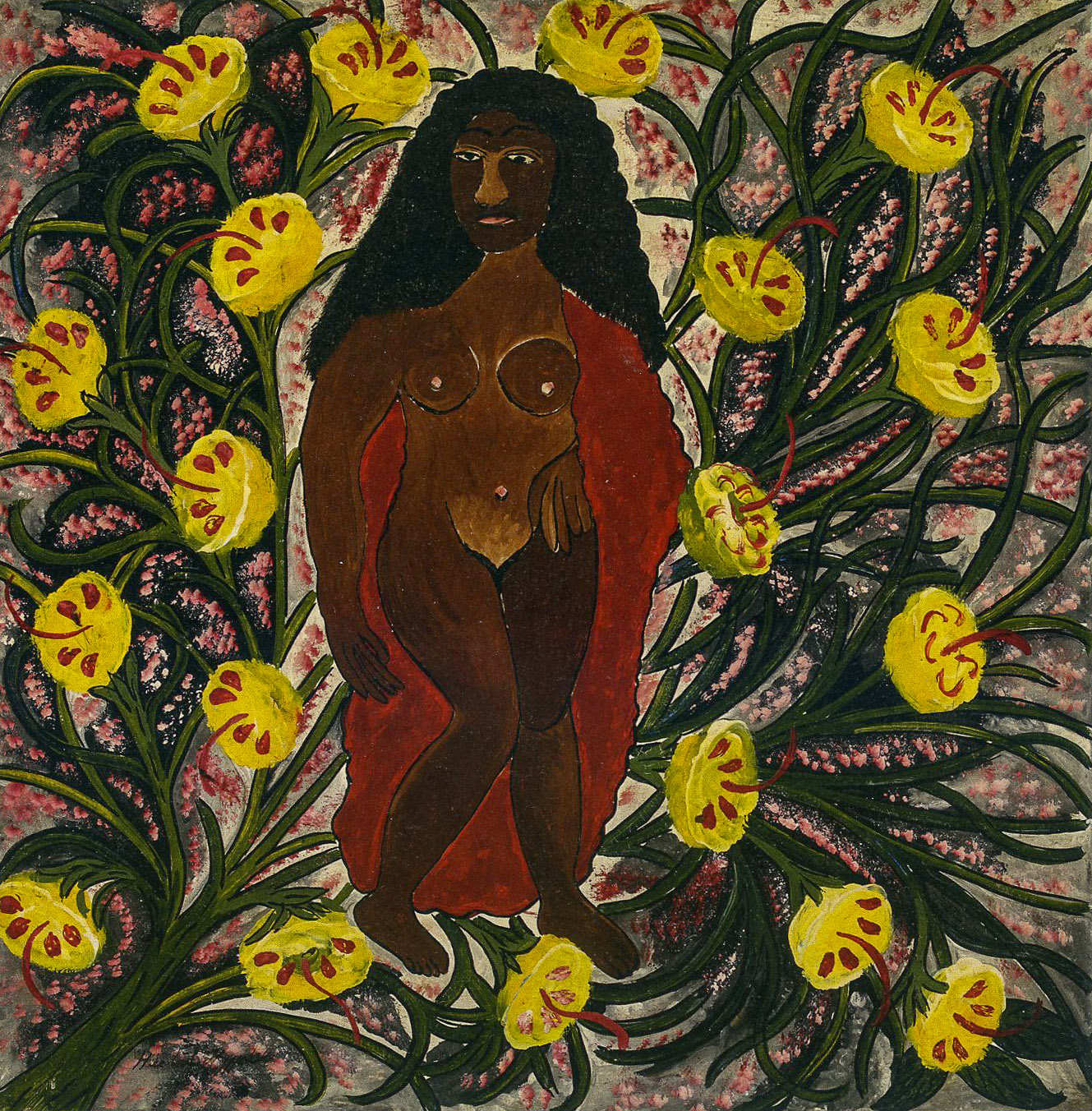

Hector Hyppolite

Hector Hyppolite’s art, best known for its vibrant depictions of nature, female eroticism, and religious fantasies, capture a sense of vitality and tension. Critics like Gérald Alexis and Édouard Glissant highlighted the hieroglyphic nature of his work, observing the aesthetic intelligence in his paintings. Though the narrative around his vocation as a Houngan, or a Vodou priest, remains closely associated with his artistic legacy — cemented by André Breton’s writings — it remains unclear if this is true or simply a part of the artist’s myth-making.

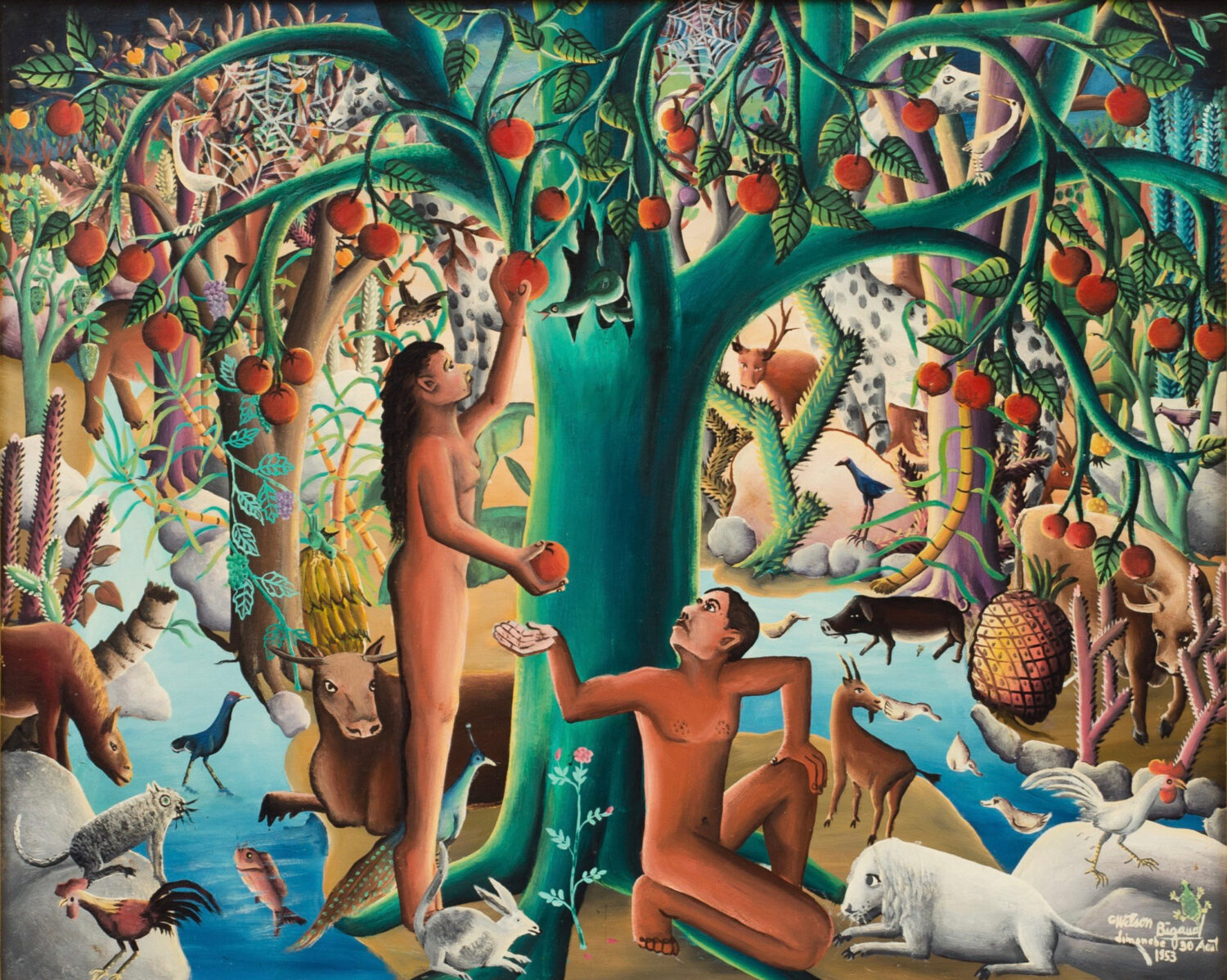

Wilson Bigaud

Wilson Bigaud found his artistic calling after observing his neighbour, Hyppolite, paint. Initially experimenting with clay sculptures, he joined Centre d’Art in 1946, where he discovered his flare for painting. Like many of his peers, art-making offered him a means to overcome poverty and express his thoughts on life. His masterpiece, the mural Marriage at Cana, painted for Holy Trinity Cathedral, vividly captures various strata of Haitian society. Bigaud’s paintings often depict worlds of duality and mystery, captured with a unique use of perspective, volume, and light.

Feature image: Hector Hyppolite, Marinet, 1947. Photo: Haitian Art Society