Interview: In Conversation with Cerith Wyn Evans

By Keshav AnandWelsh conceptual artist Cerith Wyn Evans first came to attention in the 1980s as an experimental filmmaker, often collaborating with dancers and performers during this period. Today best known for his sculptures and site-specific installations, his works draw from a rich trove of references, spanning literature, music, philosophy, photography, poetry, art history and science. Employing ephemeral elements, like air, light and time, as his primary materials, his works challenge the notion that the key characteristic of a sculpture should be its condition as a physical object.

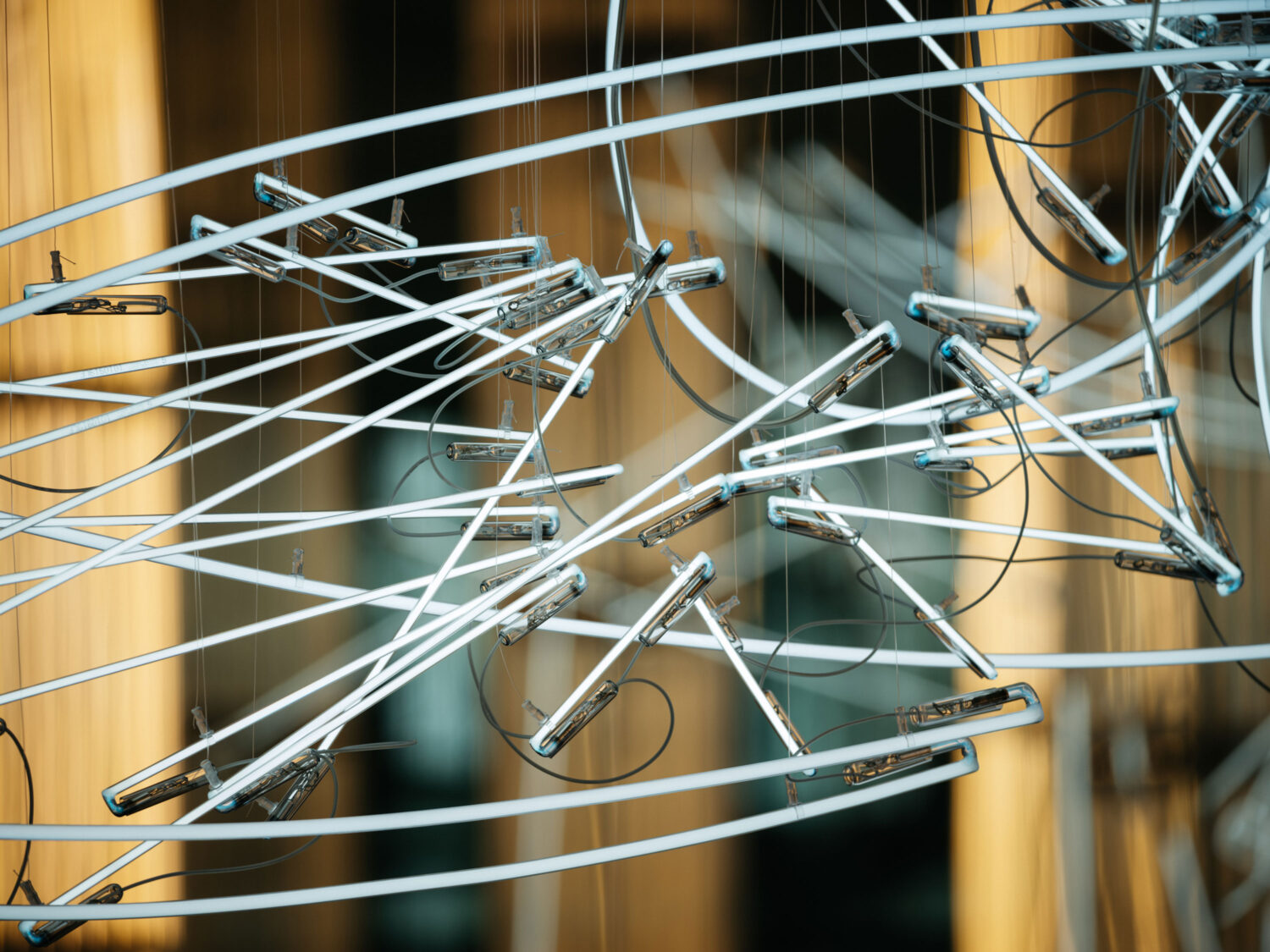

One of the most important artists of the 21st century, Wyn Evans’ works have appeared numerous times at the Venice Biennale, and have been the subject of major museum shows across the world, including presentations at Tate Britain, Aspen Art Museum, Pirelli Hangar Bicocca, and Serpentine. On the occasion of his latest show, Borrowed Light Through Metz at the Centre Pompidou-Metz, France—open now and on view until 14 April 2025—Something Curated’s Keshav Anand spoke with the artist.

Keshav Anand: How does your background in experimental film influence the work you make across sculpture and installation?

Cerith Wyn Evans: People often think they’re unrelated just because they’re different technical media, if you see what I mean. But I’ve never really been a specialist in any one medium. When I was making films, I thought of myself as a sculptor. Back when I was at St Martin’s in the late ’70s, art schools had different departments—graphic design, fashion, sculpture, painting, and so on. These were all separated, mostly by media, and the practitioners within them considered artists in their respective fields.

When I moved on to the Royal College, where I studied film, I still thought of film in a sculptural way. My “films” at that time were often installations, more than single-screen things that you’d just send off to a TV station to play on a screen. I created these kinds of environments. For instance, at the ICA’s cinematheque, where I had my first show outside art school, the films were projected in a small set-up that included a drinks trolley where visitors could help themselves. There was always a sculptural aspect to the environment. The crossover between mediums never truly materialised as a divide for me. I still work with moving images, even shooting things on my mobile phone, but I don’t think of them as being categorically different from sculpture.

KA: So it’s more of a continuum across disciplines?

CWE: Exactly. It’s not like I was a musician who then became a farmer, or a milliner who turned to watchmaking. It’s more fluid. I started making films because I wanted not to make sculpture in the formalist sense, not to have to deal with over-determined critical hierarchies around how sculpture was assessed. The atmosphere around sculpture felt constrained, and film was a way to escape that formalism. It allowed me to explore, but there was no point where I felt I’d abandoned one thing for the other. Sculpture could be something more time-based, spatially dynamic, or even cinematic.

At Goldsmiths, where I taught for years, we didn’t emphasise specific media. In the early ’80s, “Fine Art” covered a broader range, and in that context, students could cross media boundaries without raising any eyebrows. The film department had its technical requirements—cameras, production processes, contacts in that field. But I never felt this was something exclusive to a discipline or genre. Sculpture didn’t have to mean casting, modelling tools, or bronze foundries. It was a broader, expansive thing.

KA: That’s interesting. More specifically about the new show, how has the architectural design of the Centre Pompidou-Metz influenced the selection of works you’re presenting?

CWE: Enormously. It’s a unique building, and I hope you’ll get a chance to see it. The Centre Pompidou-Metz is about an hour and a half from Paris, and the aesthetic is what you might call quintessentially “Pompidou,” very similar to the original Parisian Pompidou. Inside, however, most of the galleries are conventional white cubes, with tall volumes and blank walls. But the overall architectural presence—the exterior structure—really shapes how you experience those spaces. When I first visited, I was drawn to specific galleries and spaces, such as the Forum, which is a fascinating place with multiple functions that shift with the seasons and weather.

The Forum space, for example, changes drastically depending on the time of year. In winter, it’s freezing, and there are screens that can open or close to allow a flow between the inside and the outside. In summer, the division between these spaces blurs. So in that space, I created a piece that plays on that indoor-outdoor fluidity. Mirrors line two walls, creating a strange “infinity corridor” effect, almost like a nightclub bathroom or an elevator when mirrors on both sides reflect into each other. The result is this zigzagging image, where the horizon outside Metz is folded into this surreal, panoramic effect that amplifies the cityscape into an infinite panorama. So it’s cinematic in its own way, using mirrors and light to take the environment beyond its physical boundaries.

It plays with those layers, and the reflection of the landscape pulls in the city, almost like a backdrop. The mirrors stretch that horizon, extending it into the space in this visually infinite way. It creates an entropic quality, a kind of feedback that makes you question what’s real and what’s a reflection. If you photograph it, the scene starts to resemble a vast, widescreen cinematic landscape. It’s an attempt to meld the architecture and environment, pulling Metz into the room and creating an illusory panorama.

KA: Your work often challenges the assumption that sculpture must occupy physical space. I wonder if you could expand on this line of thinking.

CWE: Yes, it really begs enormous questions—what kind of space is time, for example? I created a piece once that explored this: one part read “Time here becomes space,” while the other read “Space here becomes time.” Installed in various locations, it examined how time can be spatially defined, and vice versa.

For example, the speed of light and sound creates this relationship between time and space. The spatial and temporal can be defined by one another, so in this sense, sculpture can be temporal, or even cinematic. This piece I made once, the one that reads “Time here becomes space,” is about how something that exists across time can be perceived spatially, or vice versa. There’s a kind of play involved, an attempt to look at the space-time continuum through different lenses.

KA: In the exhibition text, you describe the interplay of natural and artificial light as a “choreography.” Can you elaborate on how these elements interact in your work?

CWE: That interplay gives the installation its temporality. So for instance, the private view begins at six, but by half-past five, it’s already dark. You realise these factors, like the shift in light, are integral to the experience of the piece. It’s like the push and pull of nature itself, where daylight flows into a space and recedes. It’s a bit like tidal movement, or the way the sun shifts across a room during the day. I find that captivating. Working with traditional neon, you’re already working with light and space in a way that’s both elemental and artificial. Neon gas, when electrified, always produces a red glow, but with other gases like argon, which gives off a blue light, you get that variance in colours people associate with “neon.” There’s a strong dialogue here between what’s considered natural and what’s artificial, and how those distinctions blur under different conditions.

I work with traditional neon materials—borosilicate glass, noble gases like neon, argon, and krypton—all elements from the periodic table. Nothing synthetic. When you break a neon tube, the gas just returns to the atmosphere, as if it was never contained. In that sense, it’s an organic material, though people consider it artificial because it’s harnessed by industry. There’s always a dialectic here between what’s organic and what’s mediated through technology.

KA: Fascinating. Talking about organic materials in your work, over the past year, I’ve seen two iterations of Still Life—in Tokyo’s Espace Louis Vuitton and Hot Wheels Athens—featuring a Japanese pine and citrus tree respectively. I’m curious to learn more about this series and the thinking behind the plants used.

CWE: Ah, I’m so glad you got to see those. This series plays on the interaction of organic and industrial. Plants are both living and static—natural yet domesticated. I often present them in revolving displays, almost imperceptibly slow, mimicking the sun’s movement. There’s a surreal quality to it. It becomes a kind of “indoor garden” that invites viewers to think about time, nature, and our influence on it. The plants’ unnatural rotations create an uncanny, almost comedic aspect, suggesting a reversal of natural processes.

There’s a long tradition of using plants to soften rigid architecture. In the high modernist period, plants were used in stark interiors as counterpoints. You’d have a Brutalist building softened by carefully placed greenery. For this series, I sometimes work with pine trees, referencing Noh aesthetics in Japan, where the stage traditionally features three pines. These little symbols carry so much meaning. And over time, I’ve come to see plants as these cultural signifiers, connecting indoors and outdoors in different ways.

KA: Changing pace for a moment, is there a film or book you could recommend to our readers?

CWE: There’s an extraordinary filmmaker named Peter Gidal. His work is in radical, structural-materialist cinema. His films aren’t for everyone; they’re abstract, often devoid of traditional narrative or figuration, and deal with extreme duration. They’re not particularly easy watching, but I find them sublime. As for a book, I would say The Fourth Dimension and Non-Euclidean Geometry in Modern Art by Linda Dalrymple Henderson.

KA: Thank you. One last thing—do you have a favourite restaurant in London?

CWE: St. John. Fergus and Margot Henderson are dear friends, and I’m the godfather to their children. But I’ll be honest, my most frequented “restaurant” is probably Deliveroo—food delivered to your door while you listen to music or watch a film is hard to beat.

Feature image: Cerith Wyn Evans, Borrowed Light Through Metz, Centre Pompidou Metz, France. Photo: Lewis Ronald